The Freedom Riders exist in American culture as an almost mythical group of heroes, a collective of brave souls, iconic and sympathetic champions of equality.

Don’t worry. You won’t read anything different here.

Indeed, the Freedom Riders were all of those things. But they were also 436 individuals who each woke up one day, unwilling to wake up to another where Black people were second-class citizens. As Diane Nash, a founder of the SNCC told us, most had put their affairs in order, and all had signed waivers releasing the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) from any liability should they be injured or killed.

Ruby Doris Smith wasn’t just one among the collective, she led by example.

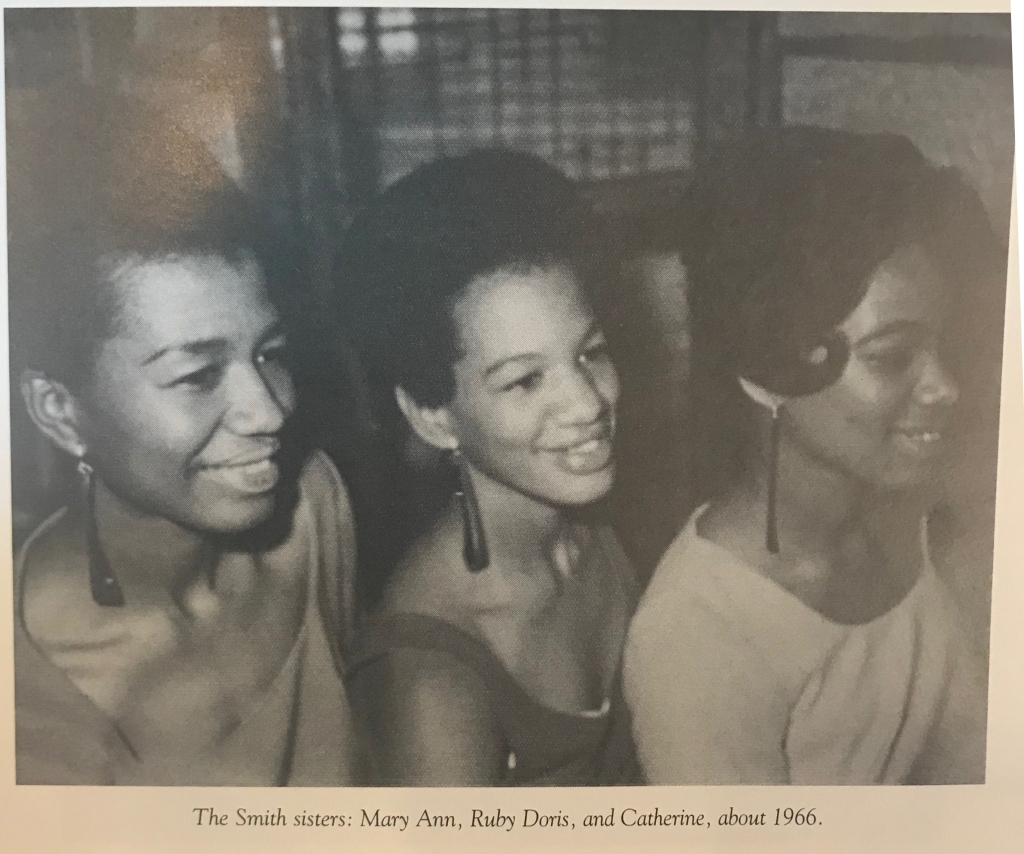

Born in 1942, she was one of seven born to beautician Alice and pastor/handyman J.T., both gainfully employed and fully involved in their community, raising their brood in all-Black schools, churches, and other social settings. With the luxury of safe and comfortable financial and social circumstances, wanting for little and surrounded by friendly faces, the Smith children grew up with certain expectations of the world, and against that backdrop, the scenes of white supremacy and racial violence outside of the Smiths’ little bubble seemed absolutely horrifying. Even as a child, Ruby Doris knew she’d been put here with purpose, and once told her sister Catherine, “I know what my life and mission is…It’s to set the Black people free. I will never rest until it happens. I will die for that cause.”

Ruby Doris’s journey started with small protests. She’d throw rocks back at white children who would tease her friends and siblings. When a white sundae shop clerk handed her an ice cream cone with his bare hand, she refused, perfectly aware that cones served to white customers came wrapped in tissue. Those were only embers of the fire still yet to come.

Whipsmart, Ruby Doris graduated high school at 16, and just kept leveling up at the historic Black women’s university of Spelman College. In 1960, Ruby had been at school less than a year and already found her calling. That was the year four well-dressed young Black men walked up to the F. W. Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, cemented their place in history and ignited a movement by simply sitting down.

That kind of defiance was right up Ruby’s alley, and she jumped head first into organizing her own publicity-making protests. “Kneel-ins” at white churches were a particular specialty of hers, but outside of holy places, Ruby Doris wasn’t afraid to be loud about her rights. “Have integration will shop, have segregation will not,” she’d chant outside of shops and grocery stores, even if no one else protested with her. By 1961, Ruby Doris had been arrested more times than she could count for her repeated rabble-rousing, and had no intention of stopping as she signed on to become the executive secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the group that had just begun organizing what they would call “Freedom Rides.”

When Ruby Doris set out on her own bus ride from Nashville to Birmingham on May 17, the KKK’s Anniston, AL firebombing had occurred just days before. Diane Nash said, “It was clear to me that if we allowed the Freedom Ride to stop at that point, just after so much violence had been inflicted, the message would have been sent that all you have to do to stop a nonviolent campaign is inflict massive violence.” So undeterred, they pressed on, and as expected, they were indeed met with more massive violence. Ruby Doris was badly beaten, but still rode on from Birmingham to Jackson, MS. And since nothing else so far had kept busload after busload of Freedom Riders from riding into the Deep South, the powers that be decided they’d try another tactic: brutal imprisonment. Parchman State Penitentiary was a Mississippi maximum security prison, and everything about the Freedom Riders’ imprisonment there was designed to be torturous to the hundreds whose rides landed them at those facilities.

Michael Booth, a member of the Civil Rights Movement remembers, “With the intention to intimidate and instill fear, the women were packed onto a flatbed, in the middle of the night, similar to that which animals are transported in. They were forced to stand the entire drive from Jackson to Parchman, going through Money, Mississippi, the place where Emmett Till was murdered. In a continued effort to break their spirits, when the women were processed into Parchman they were forced to walk through a very large pool of cockroaches before being photographed and fingerprinted. The women were imprisoned on death row where the ‘most cruel and unbelievable things’ were perpetrated on the Freedom Riders. [One woman’s] cell was only 13 footsteps from the gas chamber. The lights were left on 24 hours a day so that the prisoners didn’t know what time it was or what day it was.”

Ruby Doris didn’t document the horrors perpetrated on her at Parchman, but others remembered being scarred by what they saw done to her. The woman jailed next to the gas chamber, Dr. Pauline Knight-Ofusu, watched as Ruby Doris was “dragged barefooted down a concrete hallway to be thrown into a shower and scrubbed with a wire brush. Post traumatic syndrome is a given for every Freedom Rider,” she said. Traumatized, but still not broken. After 45 days in Parchman, Ruby Doris went right back to disrupting the way only she could.

The Kennedys were legislating the bus situation, the lunch counters had been desegregated thanks to the efforts of the protestors, but there was more work to be done. Even hospitals had “white only” entrances, and after months of organizing elsewhere, that’s where Ruby Doris turned her attention. When a receptionist tried to bar protestors from the white-only door, quipping that they weren’t sick anyway, Ruby Doris marched right up to the desk, looked that woman straight in the eye as she vomited, and replied, “Is that sick enough for you?!”

Truth is, Ruby Doris was sick. Dr. Pauline knew back at Parchman that Ruby had ulcers and diabetes. When Ruby Doris was elected as the first female executive secretary of SNCC under Stokely Carmichael, she was a wife, mother, and had a full time job. Her anxiety kept her so tightly wound that she kept a collection of glass bottles in her office specifically to break and sweep up before getting back to work. By the time she was 25, Ruby Doris Smith Robinson was dead.

Officially, a rare blood disease and terminal cancer claimed her life on October 7, 1967, but everyone involved in the movement knew her real cause of death. Stanley Wise, another leader in SNCC put it plainly: “She died of exhaustion… I don’t think it was necessary to assassinate her. What killed (her) was the constant outpouring of work with being married, having a child, constant struggles that she was subjected to because she was a woman… she was destroyed by the movement.”

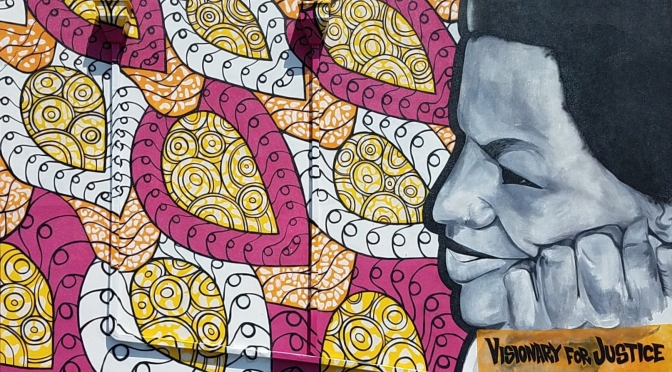

Note that Mr. Wise speaks of her death in terms of assassination because Ruby Doris was truly a driving force in the movement, and her sudden loss was deeply felt. What I’ve mentioned to you here is only a fraction of what she accomplished in her 25 years. She led voter registration drives in dangerously racist Mississippi, and single-handedly organized the SNCC’s Sojourner Truth Motor Fleet to keep the organization mobile. The work she did for Civil Rights was incomparable, and so was her mere presence. In eulogy, Stokely Carmichael said Ruby Doris “was convinced that there was nothing that she could not do… she was a tower of strength,” and on her headstone, her own words were engraved: “If you think free, you are free.”

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Spend more time getting to know Ruby Doris in her biography, Soon We Will Not Cry: The Liberation of Ruby Doris Smith Robinson.

Read SNCC’s detailing of the impact Ruby Doris left on their organization.

Browse the archives of the Civil Rights Digital Library and the Atlanta University Center Woodruff Library for more articles, letters and clippings from Ruby Doris’ life.