John Berry Meachum specialized in freedom.

Born enslaved in 1789, it took 21 years and an agreeable owner to purchase his own independence, and the first thing he did with it? Walked 700 miles from Kentucky to Virginia to free his father too.

Together, the pair walked BACK to Kentucky to liberate John’s mother and siblings. Inspired by John’s tenacity and limited in his own old age, John’s former owner, 100-year-old Paul Meachum, made a once-in-a-lifetime offer: he’d free ALL of his 75+ slaves if John would lead them out of Kentucky and into the free state of Indiana. So John did.

Little did he know there was MUCH further to go. John returned to Kentucky only to find that his wife’s owners had moved to St. Louis, MO in his absence.

Two guesses what he did next.

By 1815, John and Mary Meachum were reunited in St. Louis where he eventually purchased her liberty, that of their children, and 20 more enslaved strangers as well.

The Meachums’ story could have ended there, happily ever after with everyone they loved free.

But in 1825, he set his sights on a new brand of freedom, founding the first Black church west of the Mississippi. It still exists today as the First Baptist Church of St. Louis. Until 1847, the church’s original basement secretly housed the Tallow Candle School, Missouri’s first school for free and enslaved Black children.

Just the year before, Dred Scott threw the entire state of Missouri into turmoil when he and his wife sued for their freedom in a case that went all the way to the United States Supreme Court. Missouri was a slave state, but its laws read that “once free, always free,” and before they were brought to Missouri, the Scotts had lived in two free states. They were also were church-going people, and Black churches provided a wealth of resources rarely accessible to enslaved people in particular: literature, privacy, and abolitionists.

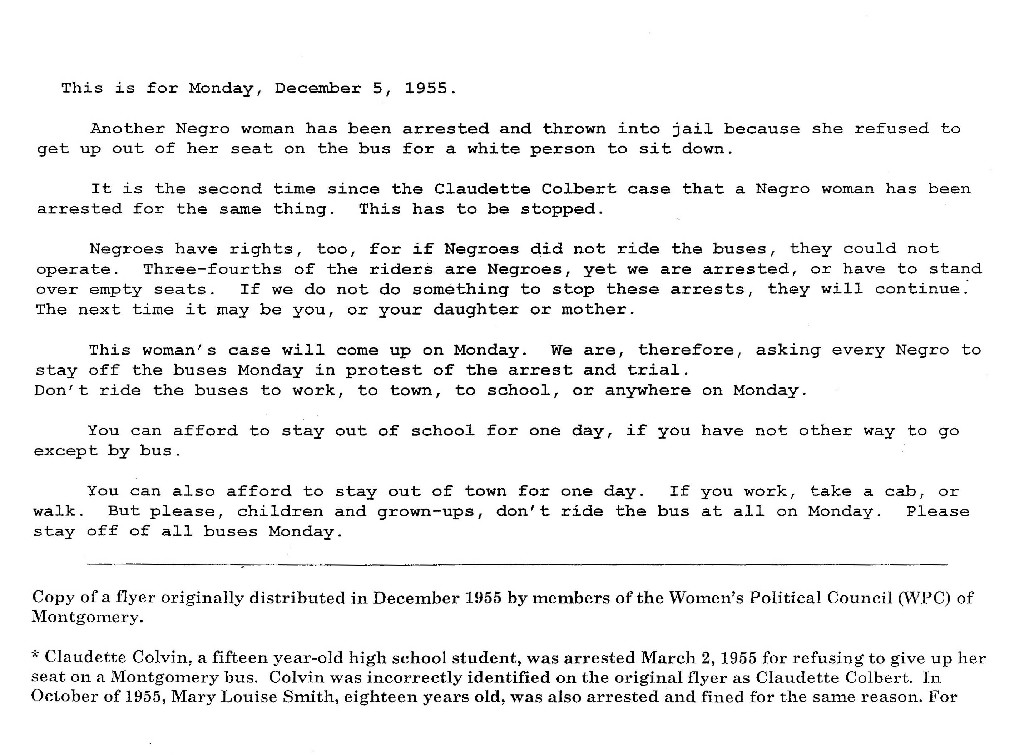

In short, Black churches were a safe haven where slaves might learn to read, and subsequently learn to escape—circumstances that Missouri had to put a stop to. With their 1847 Literacy Act, Missouri forbade Black citizens from being educated, gathering for church services without the presence of law enforcement, and more.

But the state of Missouri didn’t know Reverend John Berry Meachum’s reputation for subverting the system. Where they made laws, he’d find ways… namely, the United States’ second-largest waterway: the Mississippi River. At its banks, Missouri’s state laws ended and federal regulation began.

So John bought a steamboat, anchored it square in the middle of the Mighty Mississip’ where neither the state nor any nefarious mischief could touch it, and named it the “Floating Freedom School.”

Equipped with its own library, classrooms, and all the standard trappings of a school, the Floating Freedom School was an act of defiance in broad daylight. And because Reverend John planned so carefully, there was absolutely nothing anyone could do about it. Until at least 1860, 13 years after its commission, the Floating Freedom School remained moored in the Mississippi River.

Unfortunately though, the school outlasted its founder. The good Reverend died the same way he lived: while shepherding his flock. On a Sunday morning in 1854, he suffered a heart attack in the midst of delivering his sermon.

But his work lived on. John’s wife Mary, who herself had been bonded out of slavery decades before, went on to free hundreds more as a major conductor of the Underground Railroad. One of the National Park Service’s 700 National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom “depots” across 39 states even bears her name: “The Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing.”

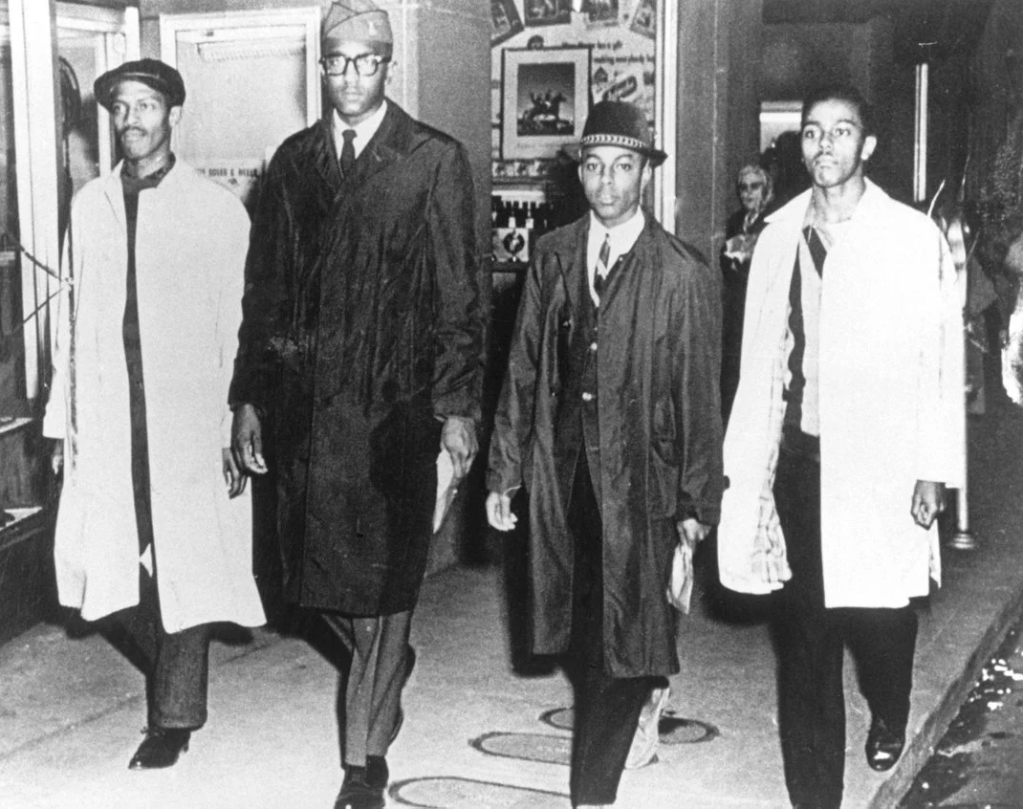

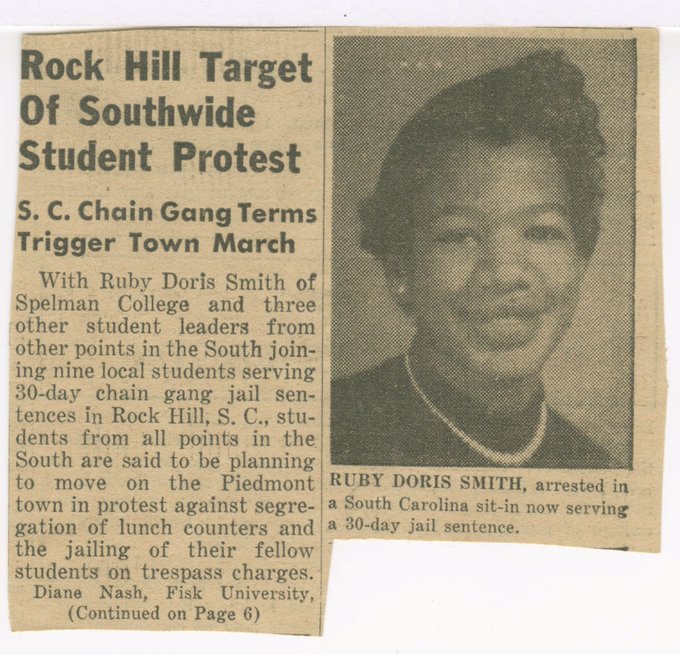

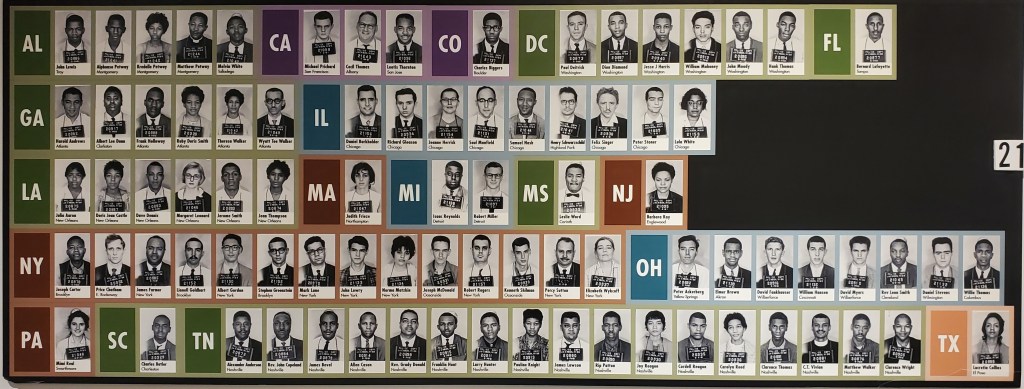

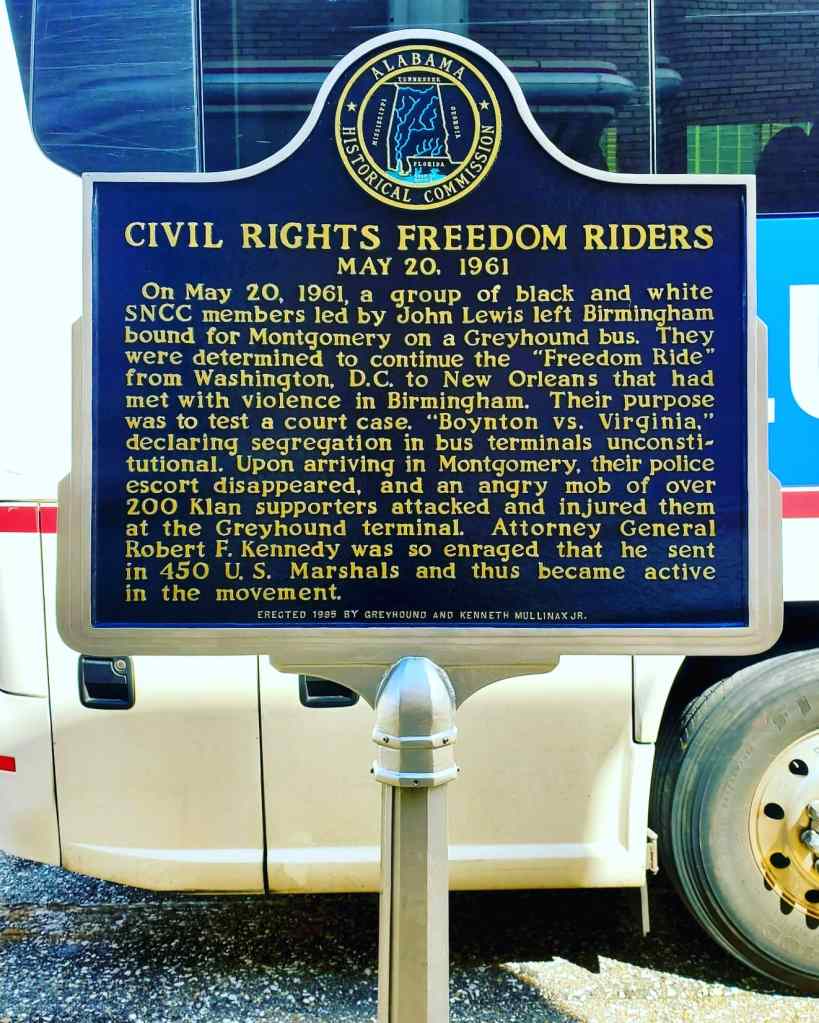

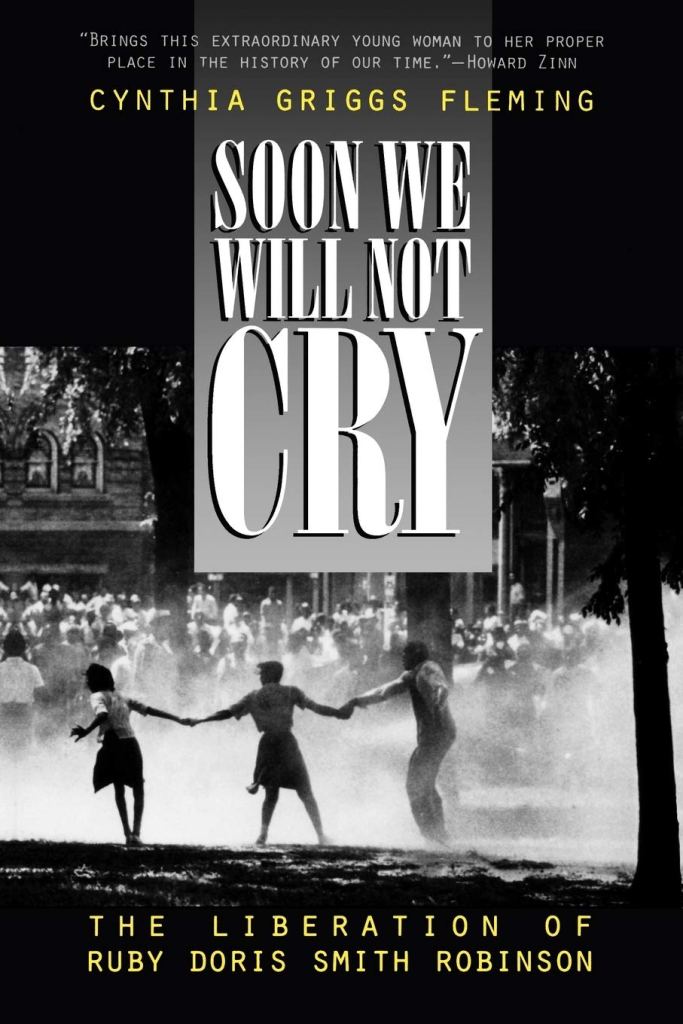

John Meachum’s Floating Freedom School also became the foundation and inspiration for more recently subversive “Freedom Schools,” created during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s to combat the “sharecropper education” Black students received in so-called “separate, but equal” schools. While their external reason for existing was to fill educational gaps, internally, the Freedom School curriculums included Black history, literature, theater and more, honoring and preserving Black culture in one of the few places they could outside the home.

All of this, set in motion by the footsteps of a man whose own freedom wasn’t enough if he couldn’t bring his people too.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Dive into more Missouri Civil Rights stories here.

Hear the St. Louis Public Radio‘s take on how “John Berry Meachum defied the law to educate” Black Americans.

Hear first-hand accounts from Freedom School students of the 1960s at the Library of Congress blog.