From the local newspaper to the locals themselves, Montgomery’s white folks liked to turn Georgia Gilmore into a fat joke.

They had no idea they were mocking the heart and soul of a movement.

The Black folks close to her knew Georgia Gilmore had presence. And it had nothing to do with her size.

She was quick-witted, clever, motherly, industrious, and every morsel from her kitchen tasted absolutely divine.

Georgia’s skill was in high demand in Montgomery’s households and lunch facilities, but the hypocrisy everywhere else in town was real. Even though Montgomery’s bus system was almost entirely reliant on domestic workers like maids, nannies, seamstresses (like Rosa Parks) and cooks like Georgia, those women took the brunt of racial abuse from drivers and passengers. By the time Rosa’s turn came around, Georgia’s personal bus boycott had already begun.

She’d gone through the mortifying motions so often it was automatic: fare at the front, walk of shame to the back. So when Georgia dropped her fare into the box in October 1955, and the driver barked at her to get off and get on again through the back door, she was more than rattled. Georgia was furious. Powerless to do any different, Georgia begrudgingly backed out. When her feet touched the pavement, the driver shut the door and drove away. She vowed to never be humiliated that way again.

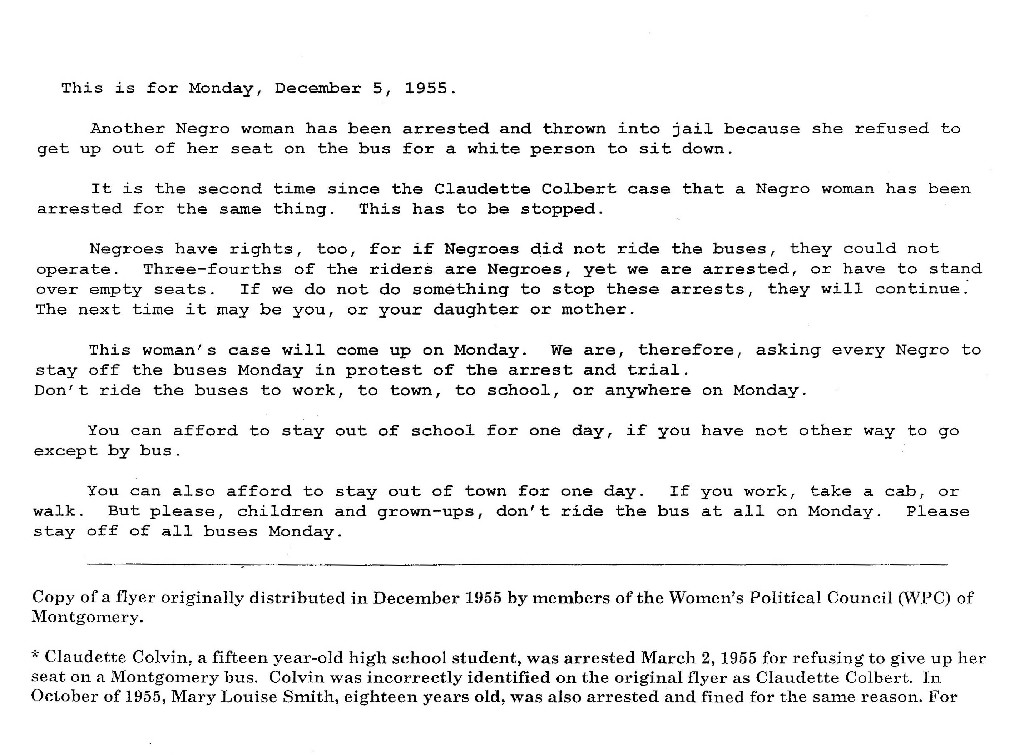

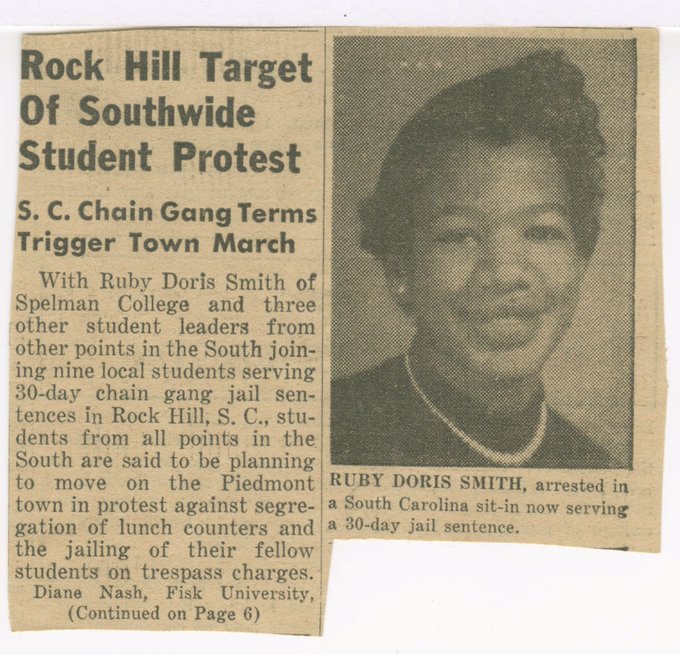

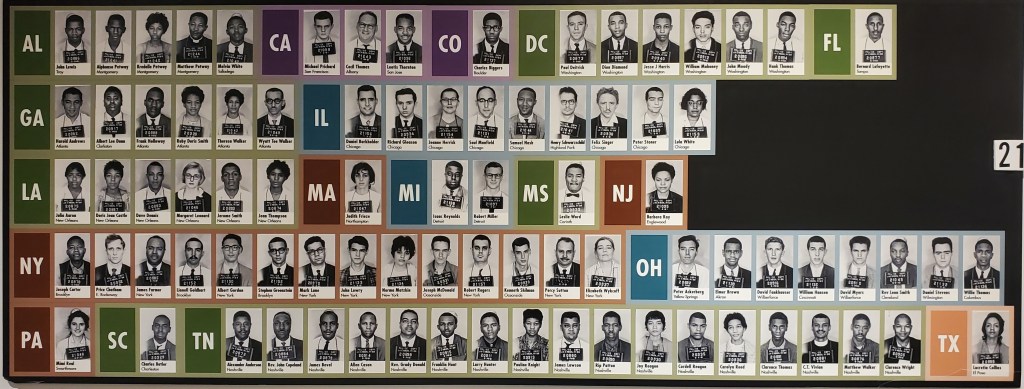

So when flyers went out alerting Black Montgomerians that an upstanding woman had been jailed for protesting the Montgomery Bus System, Georgia hightailed it to Holt St. Baptist Church where those in support of taking action gathered. She was one of nearly 5,000 there on December 5, 1956 who launched the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the first mass public demonstration of the Civil Rights Movement, and she was proud to be counted among its most crucial participants. “After the maids and the cooks stopped riding the bus, well the bus didn’t have any need to run,” she said. “It was just the idea that we could make the white man suffer. And let the white man realize that we could get along in the world without him.”

By simply existing in her Blackness, Georgia had taken some of her power back from her oppressors. And hungry for more, she put her skills to work.

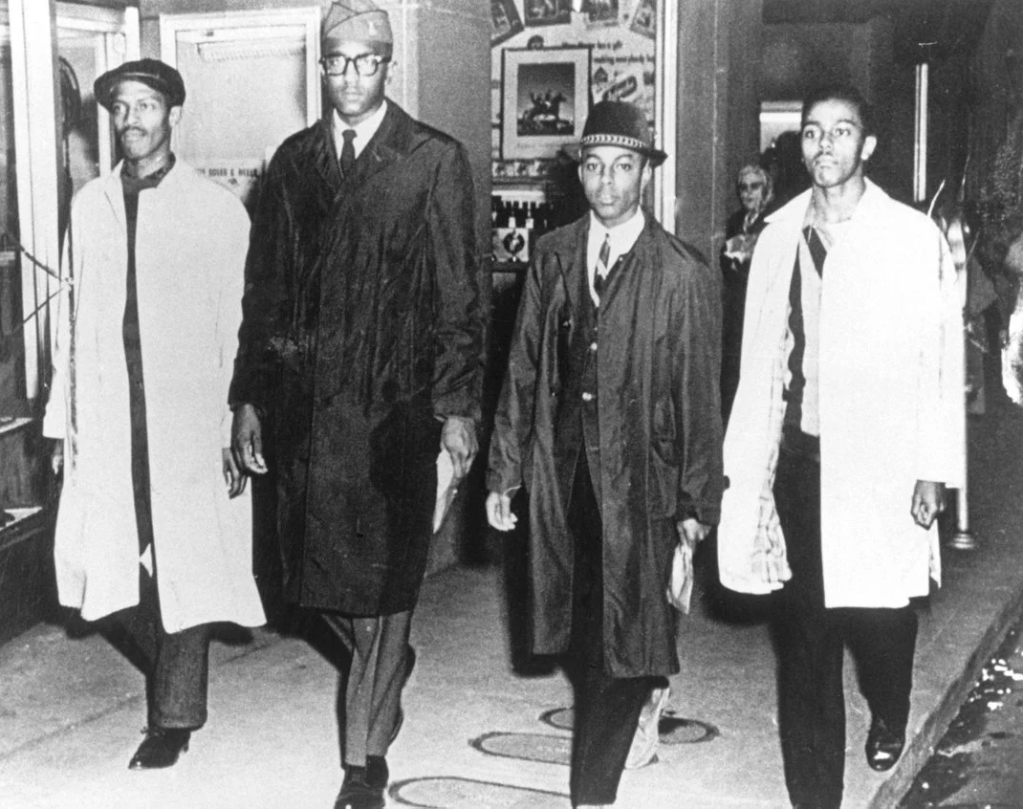

The Montgomery Bus Boycott drew supporters from outside communities too, because even Black people that didn’t live in Montgomery still had to sit in the back of its buses. Georgia had worked as a cook and a midwife, but mass fundraising against racism was brand new to almost everybody participating. But not all were in the position to participate publicly. They cooked, cleaned and cared for the children of white racists, and were suddenly forced into a choice between supporting their people and maintaining a livelihood. Carpools were formed to transport workers and named based on their geographical locations around town. But all of those car clubs needed money for gas, insurance, upkeep, all the costs one takes public transportation to avoid. Georgia rallied all of those domestic workers who wanted to help quietly into the “Club from Nowhere,” a group of women who turned plates, pies, pastries, and whatever their culinary speciality into cash money for the movement.

The Club from Nowhere provided all sorts of strategic cover. A Black maid or cook carrying food was about the least suspicious person in the Jim Crow South. Should any member be questioned about the money they carried after selling their goods, they could answer in two totally truthful ways: say that it was from selling food, OR that it came from/was being taken to “Nowhere.” Finally, white allies who couldn’t realistically attend a planning meeting to donate could write a check to “The Club from Nowhere” without revealing the true recipient of that support. Eventually, the Club from Nowhere was bringing in $200+ dollars a week (about $2K today), more than any other fundraising effort in Montgomery.

Nowhere was brilliant, and through it, Georgia came into her own, cooking and hustling for the movement. For the 382 days that the Montgomery Bus Boycott lasted, Georgia Gilmore found one way or another to support it.

The most obvious, and you’d think innocuous, was by walking. “Sometime, I walked by myself and sometime, I walked with different people, and I began to enjoy walking, because for so long I guess I had this convenient ride until I had forgot about how well it would be to walk,” she said. “A lot of times, some of the young whites would come along and they would say, ‘N*gger, don’t you know it’s better to ride the bus than it is to walk?’ And we would say, ‘No, cracker, no. We rather walk.’ I was the kind of person who would be fiery. I didn’t mind fighting with you.”

All that fire and fight made Georgia an excellent witness on the stand when Montgomery County Grand Jury indicted Martin Luther King Jr. (and over 100 others) for violating Alabama’s anti-boycott laws. Nobody had a better story to tell than Ms. Georgia who’d been left on the side of the road out of spite. She made an indefensible case for why Montgomery’s buses needed to be desegregated: “When I paid my fare and they got the money, they don’t know Negro money from white money,” Georgia testified.

But that visibility also made Georgia an easy target.

She appeared in the pages of the Montgomery Advertiser repeatedly after that, always as the aggressor, always as a laughingstock.

The Alabama Journal, November 3, 1961: “Huge Negro Woman Draws Cursing Fine.”

The Montgomery Advertiser, on the same story: “A hefty Negro woman who weighed in excess of 230 pounds was fined $25 today in city court on charges of cursing a diminutive white garbage truck driver.”

As the Safiya Charles of today’s Montgomery Advertiser writes, “he worked a twist on the sassy Black mammy archetype. And he rendered the white male truck driver her victim.”

But Georgia would not be deterred by outside opinions. Because her home was full of love. Though the papers called her the most derogatory names, the people who came from far and wide to buy Georgia’s plates of fried chicken and macaroni and cheese, or sit at her table sipping sweet tea called her “Georgie,” “Tiny,” “Big Mama,” and “Madear.”

(Those near and dear guests of her kitchen included Martin Luther King, Aretha Franklin, Sam Cooke, and even Lyndon B. Johnson and Robert F. Kennedy.)

On December 20, 1956 the boycotts ended after the Supreme Court ruled the buses’ segregation unconstitutional, but Georgia’s reputation had been so utterly tattered that she was certain her days of working in Montgomery were through. Between her activism, her testimony, her attitude, and the press, she couldn’t even get home insurance.

Georgia deserved to be rewarded for her courage and dedication to the movement, not left in shambles because of it. “She was not really recognized for who she was, but had it not been for people like Georgia Gilmore, Martin Luther King Jr. would not have been who he was,” Rev. Thomas Lilly who participated in the boycott, said. Dr. King himself repaid at least some of that debt with the most valuable piece of advice Georgia ever received. “All these years you’ve worked for somebody else, now it’s time you worked for yourself.” She did, and she never worked for anyone else again.

Still at it decades later, on March 3, 1990, in preparation for the 25th anniversary of the March from Selma to Montgomery, Georgia cooked up her famous macaroni and cheese and fried chicken to feed the revelers. Hours later, she passed and had the honor of watching her table from above as hundreds gathered to grieve her and commemorate so many walks for freedom with one last meal from from nowhere.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Georgia in the New York Times’ Overlooked series.

Southern Foodways collaborated with the Montgomery Advertiser to celebrate Georgia’s life, and make amends for how she’d been represented in the Advertiser’s pages. It’s a beautiful read, by another Black woman and I encourage you to enjoy it.

PBS series “Eyes on the Prize” has captured interviews with members of the Alabama civil rights movements, and you can find Georgia’s here:

INTERVIEW 1 (1979) | INTERVIEW 2 (1986)

Listen in to the personal accounts of many who had the pleasure of eating in Ms. Georgia’s kitchen, including her son, Montgomery City Councilman Mark Gilmore, in NPR’s “The Kitchen of a Civil Rights Hero. “

Councilman Gilmore was gracious enough to share Georgia’s Legendary Sweet Tea recipe so we can raise a glass to her.