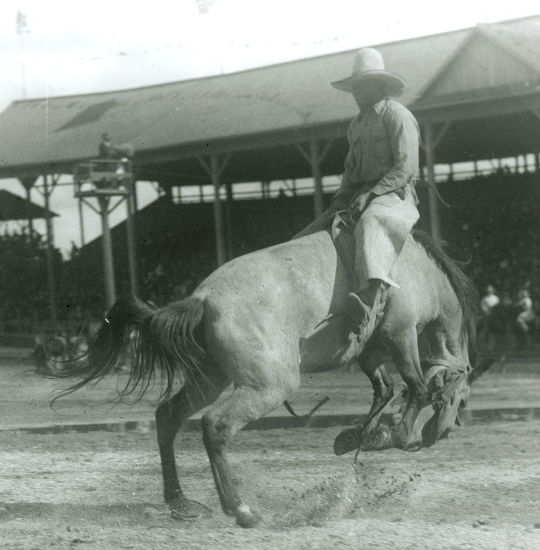

Every 8 seconds, Jesse Stahl’s life must have flashed before his eyes.

He was more than “just” a rodeo rider.

Jesse Stahl demonstrated some of the most legendary horsemanship the world’s rodeo circuit has ever seen.

When his name was called, the whole arena knew they were about to see the show of a lifetime.

They also knew that no matter how skilled, how risky, or how dazzling Jesse’s ride, there was no way he’d actually win.

Though his talent was famously touted far and wide, Jesse Stahl was infamous, even among his competitors for “winning first, but getting third.”

No matter how hard Jesse rode, almost all of the judges he faced refused to score his ride higher than a white man’s. Dozens of others would allow him to ride for show, but wouldn’t let him compete at all.

The adage is that we have to work twice as hard to get half as far. And Jesse worked even harder, becoming widely renowned for feats of horsemanship no other cowboy would even attempt.

His pièce de résistance was riding a bucking bronco backwards. As if that weren’t already incredible, Jesse’s routine variations on that trick were almost superhuman.

He and Kentucky Black cowboy Ty Stokes often teamed up for what they called the “suicide ride,” where both men rode a bucking bronco simultaneously, with Ty facing forward and Jesse facing backward. According to another cowboy, Jesse even rode at least once backwards with a suitcase in his hand, exclaiming “I’m going home!”

But riding backwards was hardly the only trick up Jesse’s sleeve.

“Hoolihanding,” the act of jumping from the back of a horse directly onto a bull’s before taking it down by the horns was invented and perfected by Jesse before it was eventually outlawed as too dangerous for the animals.

(Fellow Black cowboy Bill Pickett altered the move, jumping from a horse to simply wrestle a steer down by the horns, inventing what’s today known as “bulldogging.”)

A 1912 rodeo in Salinas, CA brought Jesse one of his most fearsome opponents, a bucking bronc forebodingly named Glass Eye. This unbroken horse terrified other competitors, but Jesse handled the gravity-defying ride with such ease, he even had time to ham it up.

Despite these daring displays that literally put his life on the line, most sources—from fellow cowboys to local oral histories to museums—all agree that Jesse rarely ever won.

But as 2019 Blackstory feature Shelby Jacobs said, “If you impress the crowd, the coach can’t put you on the bench.”

Jesse may not have been able to win the judges, but he had so much crowd appeal, that today, some local writers credit Jesse for putting whole rodeos on the map, while giving him the superstar status of a “cowboy Steph Curry.”

And his fellow riders loved him most of all. Because Jesse depended on rodeos that would allow him to ride AND place well AND pay him—all tall orders for a Black person in the early 20th century—he died penniless. Rather than allow a legend to rest in a pauper’s grave, friends and competitors paid for his proper burial.

And though his name receded into history for a while, he was finally honored by the whole of the rodeo industry with his 1979 induction into the National Rodeo Hall of Fame, only the second Black cowboy after his friend Bill Pickett.

Like so many other incredible Black people, Jesse’s only just recently begun to receive his flowers. It speaks not only to the resurgence of Black cowboy culture, but why it had to resurge in the first place.

Leaps and bounds beyond his competitors, one single attribute kept Jesse Stahl’s name in the depths of history: his Blackness.

In the wake of that resurgence, we’re celebrating brand new milestones like the 8 Seconds Juneteenth Rodeo where I first learned of Jesse’s marvelous rides, and most recently, Beyoncé’s wins for her debut country record Cowboy Carter, including Best Country Album, the first EVER in the genre by a Black woman.

One of many unsung Black rodeo cowboys, and perhaps one of the best of any race, Jesse Stahl’s legacy made way for the spectacular accomplishments Black people are making in the rodeo, Western lifestyle, and country music industries today. Every moment of it that we’re able to enjoy now, he fought for 8 seconds at a time.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Learn more about Jesse’s exploits and those of many other Black Cowboys at the Oregon Historical Society.

Browse a more complete list of Jesse’s nationwide appearances & accomplishments over his decades on the rodeo circuit at The Active Historian.

Read “Let’s Go, Let’s Show, Let’s Rodeo: African-Americans and the History of Rodeo” at JSTOR.