Even though Ella Grigsby was born free, she still carried a slavemaster’s surname. Just 10 months earlier in January 1865, the 13th Amendment ensured that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude… shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

As human property in South Carolina, her parents had no choice in being labeled with their owner’s name.

As a free woman, Ella chose a new one, vowing that she’d never be owned by anyone again.

With nothing particularly extraordinary about her, Ella Williams would have disappeared into history…

…if a bout of malaria when she was 14 hadn’t yielded an extreme side effect: Ella kept getting taller.

And taller. And TALLER.

And by the time she stopped growing, Ella Williams stood at least seven feet tall.

Today, that would be exceptional.

But height & weight trends published by the USDA note that in 1866, US senators standing 5’8″ “exceed (in height) the average of mankind in all parts of the world as well as the average of our own country.”

By those standards, Ella wasn’t just exceptionally tall—she was a giant. And that got BIG attention. Circus owners and show business agents flocked to her door, promising unimaginable riches. Just sign on the dotted line…

…a premise she absolutely refused.

As human property stolen from Africa, Saartje Baartman had no choice over her nude body being displayed to paying Europeans, then her dead body too.

As a free woman, Ella had pride and agency. She paid her bills through honest work, tending to the home of a South Carolina couple.

Until the bills started coming faster than the paychecks.

Selling out still wasn’t an option. But neither was starving. So Ella chose Door #3: stardom.

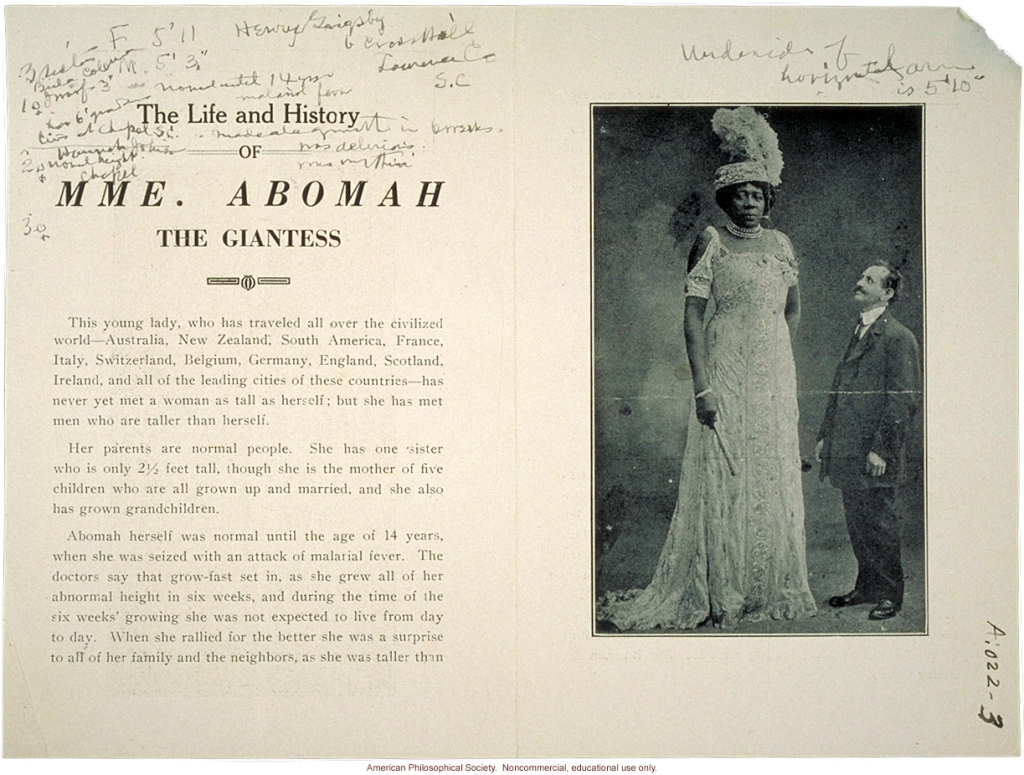

At 31 years old, Ella Williams was once again reborn as Madame Abomah.

![[page heading] The Life and History of MME, ABOMAH, The Giantess [end page heading] ...any of the men folks in the neighborhood, and she was so frail looking and thin that it looked impossible for her to live. When she first rallied for the better, she had to be supported about the house just like a child learning to walk alone. It was said by all who saw her after she first recovered from the six weeks' illness that it was impossible for her ever to get strong again. In about three months, when the cold frost came on and the cold snow began to fall, she got stronger and healthier, but still remained thin for about three years, when all of the malaria vanished and new life began. From year to year she gained weight. While touring Australia and New Zealand her weight was more than four hundred pounds and today she weighs more than three hundred and fifty pounds. Her height is seven feet eight inches, she is forty-six years of age and single, but looking for a husband. Abomah has toured as follows: In 1900, in England, with Reynolds Exhibition, six months; in 1901, at the Alhambra, Blackpool, England, three months; in 1902, the same; in 1903, three months with Reynolds Exhibition, Liverpool and six months in Australia, for J. J. Miller and Son; in 1904-05-06-07-08, touring New Zealand, with John and Ben Fuller; in 1909, in South America, under Manager S. Maranda; in 1910-11, touring France, Italy, Switzerland, Bellgium and Germany, with Manager or Emposier E. Waldmier; in 1912-13, Reynolds Exposition; 1914, touring the variety; 1917, Dreamland, Coney Island, and Cuba for S. W. Lumpertz; 1918, touring America with Barnum and Bailey Circus.[next page heading] THE LIFE AND HISTORY OF MME. ABOMAH THE GIANTESS [end next page heading]](https://theamericanblackstory.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/837-mme-abomah-giantism.jpg?w=753)

“Madame Abomah” was a name chosen for both form and function. A different tall woman named Ella was already touring nationally, so audiences needed a way to distinguish the two.

But furthermore, “Madame Abomah” gave Ella a backstory and a brand. She was no one’s sideshow act. Madame Abomah was royalty. The name was a direct reference to Abomey, capital of the affluent Kingdom of Dahomey, known for its fiercely fighting female warriors. If that sounds familiar, you might recall the Dahomey Warriors as the inspiration for the Dora Milaje of Marvel’s “Black Panther.”

Mind you, Madame Abomah wasn’t an exotic spectacle decked with hoops, shells and a spear either. Instead, she towered over women and men, dripping in lace. Seamstresses stood on tiptoes to lay jewels on her chest. Madame Abomah was the picture of style and grace supersized.

Though it was now a “free country,” most performing venues were still segregated, so white audiences’ exposure to Black performers was largely limited to blackfaced minstrels and Black people with disabilities styled as “human oddities.” The ringmaster of “Greatest Show on Earth” even built his career on the back one of those Black people.

Joice Heth was an elderly enslaved woman so whittled and worn by time and hard labor that she was blind and paralyzed. P.T. Barnum rented Joice Heth from her enslaver, and reinvented her as his very first sideshow act: the 161-year-old nursemaid to George Washington. Not one bit of that was true, but it didn’t stop audiences from paying good money to see her, or popular newspapers from “covering Heth’s shows breathlessly,” according to the Smithsonian. On the other hand, The New England Courier roasted Barnum while painting a vividly gruesome picture of Joice’s treatment, writing, “Those who imagine they can contemplate with delight a breathing skeleton, subjected to the same sort of discipline that is sometimes exercised in a menagerie to induce the inferior animals to play unnatural pranks for the amusement of barren spectators, will find food to their taste by visiting Joice Heth.” Barnum even profited from her death, charging spectators for her public autopsy.

Madame Abomah was no “animal” imprisoned to a circus tent, and she refused to be another Black woman treated like one. Fleeing American stereotypes and exploitation, Madame Abomah traveled the world. In the UK, she was a nanny by day who performed at the famed London Music Hall by night. In New Zealand, her name graced headlines written in Māori. In Germany, she snuggled babies and laughed with children, instead of terrifying them from behind a velvet rope.

For 30 years, Madame Abomah’s story is almost exclusively told through newspapers and photographs captured around the world. But in 1914, Britain declared war on Germany, and the United States was soon to follow them into World War I, making it dangerous to be an American citizen abroad. It was here that Madame Abomah disappeared back into obscurity.

With the war in full swing, the demand for entertainment slowed to a halt, and after a lifetime of performing, there were few options available to an aging, Black tall woman. In her last known photos, Madame Abomah appears among the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey’s Congress of Freaks and at Coney Island. And though the once-tall feather in her fascinator reflects the unfortunate downturn in her career, there Madame Abomah stands with her head held high as a Black woman who repeatedly defied her labels as property to chase her destiny as a big star.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Learn about “A Brief History of the Business of Exhibiting Black Bodies for Profit” at Grid Philly.

There’s more about “African Americans and the Circus” at the Smithsonian Museum of African-American History.