Greta Garbo, Marilyn Monroe, Marlene Dietrich, Joe DiMaggio, Marlon Brando, James Dean, Grace Kelly, Jean Harlow, Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Rita Hayworth, Lauren Bacall, Katherine Hepburn, Lana Turner, and Bette Davis.

Notice anyone missing?

(Aside from a single Black person? I digress.)

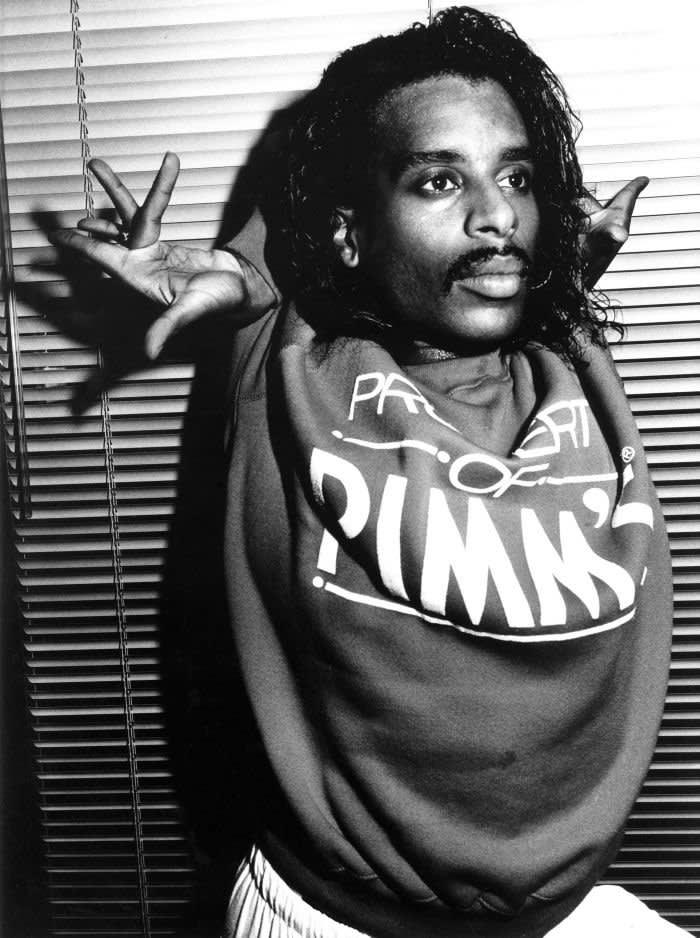

If there’s one name that unequivocally belongs among those listed in Madonna’s “Vogue,” it’s Willi Ninja.

He’s frequently described as “the Godfather of vogueing,” but I’m not sure he’d care for that title because Willi Ninja was a mother, honey.

And he got it from his own.

If you recall from Marie Van Britten Brown’s post, being a mother in Queens where Willi was born in 1961, was a tough gig. The borough was in the thick of a heroin epidemic, civil rights protests, and turmoil over the Vietnam War. Hardly what we’d call a “safe” neighborhood for raising children, but Ms. Esther Leake did her best. That included recognizing when her son (then known by William Roscoe Leake), who was a brilliantly budding dancer, was also quietly but deeply struggling with being “different” than the other boys on the block.

Willi never exactly “came out” to his mother. She coaxed him out, and not only supported his pursuits of dance and fashion, but encouraged them. Willi developed his own approach to voguing, the Harlem gay underground’s preeminent dance form, closely studying the movements of dancers like Michael Jackson and Fred Astaire, Olympic gymnasts, Asian martial artists, and the figures drawn in Kemetic hieroglyphics. (“Kemetic” refers to ancient Egypt, known as Kemet, or “black land”) And then he perfected it, diving headfirst into gay dance communities popping up around New York’s famous queer outdoor gathering places like Christopher Street Pier.

Those spaces became the forerunners and foundations of New York’s LGBTQ ballroom culture. Technically, ballroom culture has existed globally for centuries, but its earliest appearances in New York were to flout laws against wearing “clothes associated with the opposite gender.” Though those early balls were integrated, the judge’s panels were all-white, driving African- and Latino-American dancers back to Harlem’s underground in the 60s and 70s where they established their own balls . Fresh off the heels of Marsha P. Johnson’s stand-off at Stonewall, New York’s gay culture had been empowered to stand its ground, and ballroom culture let them claim space where gender, race, sexuality, and class had no place to define them.

Having always known acceptance, thanks to his mother, in the ballrooms, Willi danced with a freedom and confidence unlike anyone else in the scene, and those iconic moves made him a fixture of New York ballroom culture. But the society Willi and his fellow pioneers rejoined outside of the balls cast all the glam and good vibes they celebrated inside into stark contrast.

There, LGBTQ teenagers outcast from their families after coming out or running away had nowhere else to go but the streets. Gentrification was beginning to push lower-income families in Brooklyn and Manhattan out of their homes already. Non-profit organizations and shelters in the midst of a Reaganomics depression had less to go around than ever. Unemployment was at an all-time high. If that New York was unsafe and uncertain for everyone, it was especially so for a 16-year-old transgender person.

From those circumstances, houses were born. Each “house” specializes in an aspect of ballroom culture. They’re headed by a mother or father, and its children are cared for with food, shelter, clothing, or simply love and encouragement, by all their brothers and sisters. And the House of Ninja grew to become one of the most long-lasting and well-respected of them all. Willi welcomed people from all walks of life into his house, becoming “mother” to one of the most inclusive houses in ballroom culture, even as it endures today. That influence Willi brought to ballroom is also reflected today in long-running and tremendously diverse TV representations of LGBTQ characters like those in “Pose,” “Ru-Paul’s Drag Race,” and “Queer Eye.”

As the ranks of his house expanded, so did Willi’s own dance skills, becoming so absolutely flawless and otherworldly that even mainstream entertainment took notice. Willi danced alongside Janet Jackson in two of her Rhythm Nation videos, walked runways for couturiers Thierry Mugler and Jean-Paul Gaultier, and even taught supermodels like Iman and Naomi Campbell how to own a catwalk in ways only he could.

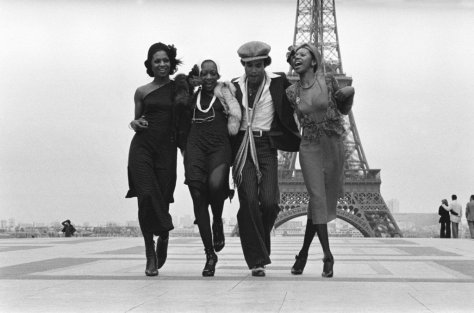

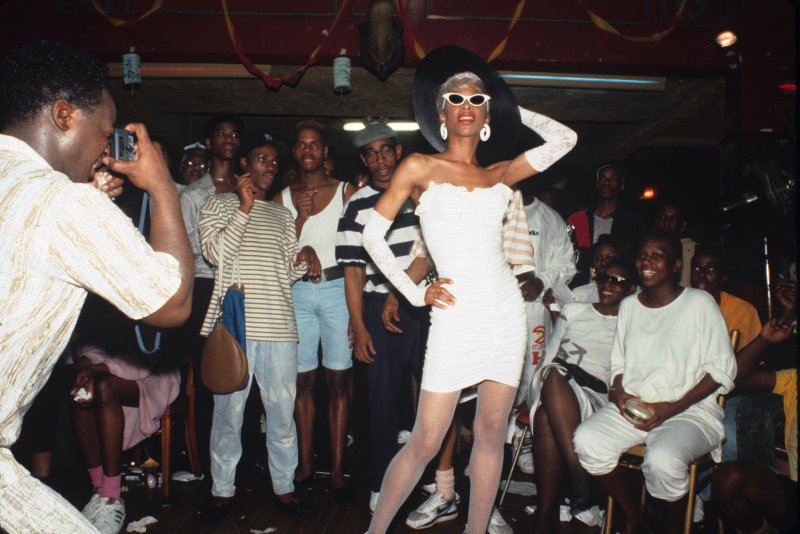

Of course, all of that was behind the scenes. If you’ve ever heard Willi Ninja’s name before, it is almost undoubtedly associated with the landmark documentary “Paris is Burning.” The film, preserved by the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry, is compiled from six years of study, interviews, first-person footage, and immersion into the African-American, Latino-American, gay and transgender communities forming New York ballroom culture. The filmmaker Jennie Livingston describes it not as a dance documentary, but a tale of “people who have a lot of prejudices against them and who have learned to survive with wit, dignity and energy.”

But not all did survive. Willi’s endlessly shooting star was snuffed out by yet another American social ill: the AIDS epidemic. In his 45 short years, Willi Ninja was instrumental in launching vogue and ballroom culture into the global phenomenon it is today, and brought the community, the triumphs and the plights of Black and Latino LGBTQ faces to the forefront of mainstream culture. Willi died on September 2, 2006 from AIDS-related heart failure, giving everything he had for his children, right down to the last beat. As family does, the House of Ninja returned that love, using their ballroom winnings to care for Willi’s mother in his absence.

All no thanks to Madonna.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

French photographer Chantal Regnault spent 3 years photographing Willi & the Harlem ballroom scene. This post’s cover photo is from her series, and accompanies Chantal’s first-person account of her ballroom experience, which you can read here.

TIME Magazine recognizes the history of voguing and the importance its culture still holds for marginalized people today.

Even the Financial Times has in-depth articles on “how the mainstream discovered voguing.” My how far we’ve come.