Everybody knows that in 1968 Shirley Chisholm was the first African-American candidate to run for United States President, right?

Right! She actually gets a brief mention in American history books, so surely that’s right…

…right?

Not even close.

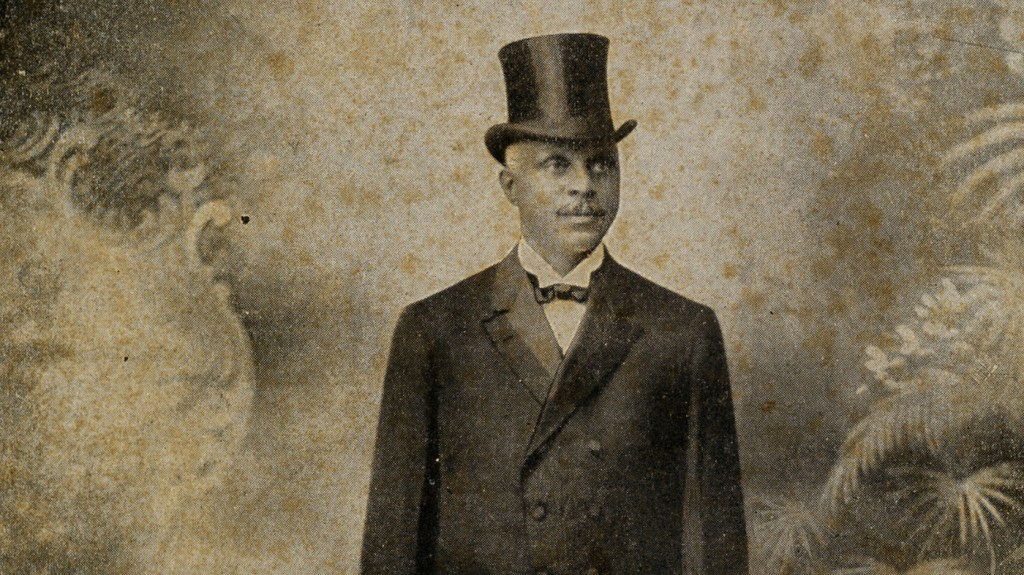

64 years before Shirley, a man you’ve never even heard of tossed his hat into the presidential ring. His name was George Edwin Taylor and the reason you’ve never heard of him is because radical Black independents don’t make the history books.

But before we get into the specifics, let’s start at the beginning, because George lived a life that came full circle.

Born in 1857, he was only two years old when Arkansas passed the Free Negro Expulsion Bill, ordering all free Black people to vacate the state of Arkansas, or else find themselves re-enslaved for a full year to cover their own relocation fees. So to be clear, the offer was leave on your own now, or be enslaved and ultimately put out a year later. Of the state’s 700 free Black people, all but 144 took option A.

George’s mother was one of those people, and fled to the free state of Ohio where she and her son could live in their peace. But their shared peace was short-lived when she died just three years later. George was a 5-year-old orphan, with nothing and no one to call his own. For three years, he survived as a street urchin, until he was finally taken in by one family, assigned to another through foster care, and went on to a Wisconsin prep school. Even if he’d stopped achieving there, folks would have considered George a success for his time, his race, and his circumstances.

But for better or worse, George had a penchant for pushing the envelope, and good enough simply wasn’t. Over the next 20 years, he excelled in writing and operating an assortment of news publications, which gave him an intimate knowledge of political issues facing African-Americans and the country as a whole. And that knowledge came in handy in 1904 when the National Negro Liberty Party asked him to him run as their leading man.

Here’s the kicker. Founded in 1897, the National Negro Liberty Party, formerly known as the Ex-Slave Petitioners’ Assembly, originated in Little Rock, Arkansas, where George had been born 40 years earlier. After the Free Negro Expulsion Bill that drove George & his mother out of Arkansas, it’s no wonder folks assembled politically against the state’s tyranny, and absolute kismet that the man who would come to represent those people nationally was born amongst them.

The Ex-Slave Petitioners’ Assembly was originally formed seeking legislative reparations of any sort after the “40 acres and a mule” that were promised did not materialize and “the poverty which afflicted [African-Americans] for a generation after Emancipation held them down to the lowest order of society, nominally free but economically enslaved,” as Carter G. Woodson put it in The Mis-Education of the Negro.

After years of trying (and failing) to push bills through Congress, the National Negro Liberty Party decided they’d shake another branch of government. And George was JUST the man for the job. He didn’t have the statesmanship of men like Frederick Douglass or W.E.B. DuBois. Their visibility among Black and White Americans helped them to temper their passions and find delicate ways to deliver harsh words to hearts and minds.

George wasn’t that dude. He’d been both a Democrat and Republican, until they’d both offended him by rejecting proposals brought to them by Black delegates, backing candidates with clear racist platforms, and failing to take up issues that only affected people of color, but when George went full scorched earth against the Republican Party by printing “A National Appeal, Addressed to the American Negro and Friends of Human Liberty,” it was game over for any affiliation he might even hope to gain with those parties. He was officially a radical independent.

The National Negro Liberty Party shortened their name to remove “Negro,” as every American ought be in favor of liberty, and delivered their party’s demands:

- Universal suffrage regardless of race

- Federal protection of the rights of all citizens

- Federal anti-lynching laws

- Additional black regiments in the U.S. Army

- Federal pensions for all former slaves

- Government ownership and control of all public services to ensure equal accommodations for all citizens

- Home rule for the District of Columbia

A very reasonable platform, but one that even George knew was unlikely to be taken seriously. “Yes, I know most white folks take me as a joke,” he said in interviews. “But I want to tell you the colored man is beginning to see a lot of things that the white folks do not give him credit for seeing. He’s beginning to see that he has got to take care of his own interests, and what’s more, that he has the power to do it.”

That Election Day was not a day of power for us. George’s name wasn’t added to a single state’s ballot. Though estimates say he received as many as 70,000 write-ins, none of that can be verified because his votes weren’t tallied in individual state records that only counted Democrats and Republicans. In fact, the only real success that George personally reaped in his presidential bid was that he came out of it alive. “He was a black man running on a third-party ticket in a country that had little interest in black men or third parties,” Trinity College historian Dr. David Brodnax said.

Between that sad but true reality and all the bridges that George had burned to get there, his national political ambitions were essentially one and done, go big or go home. But he actively continued making what strides he could by continuing his publishing career, supporting local politicians and community organizations, and empowering the Black community. He’d implored that same community on Emancipation Day in 1898 to “press on until [you have] reached the top of the ladder and then reach up to see if there isn’t another ladder on top of that one.” Then, in spite of his own certain failure, he took a leap that extended that ladder just a little further for those who’d climb next, even if American history never acknowledged his steps.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Discover more about “A Forgotten Presidential Candidate from 1904” and the circumstances that led to his nomination at NPR.

Dive into the photos, articles, and documents on George Edwin Taylor archived at the University of Wisconsin—La Crosse.

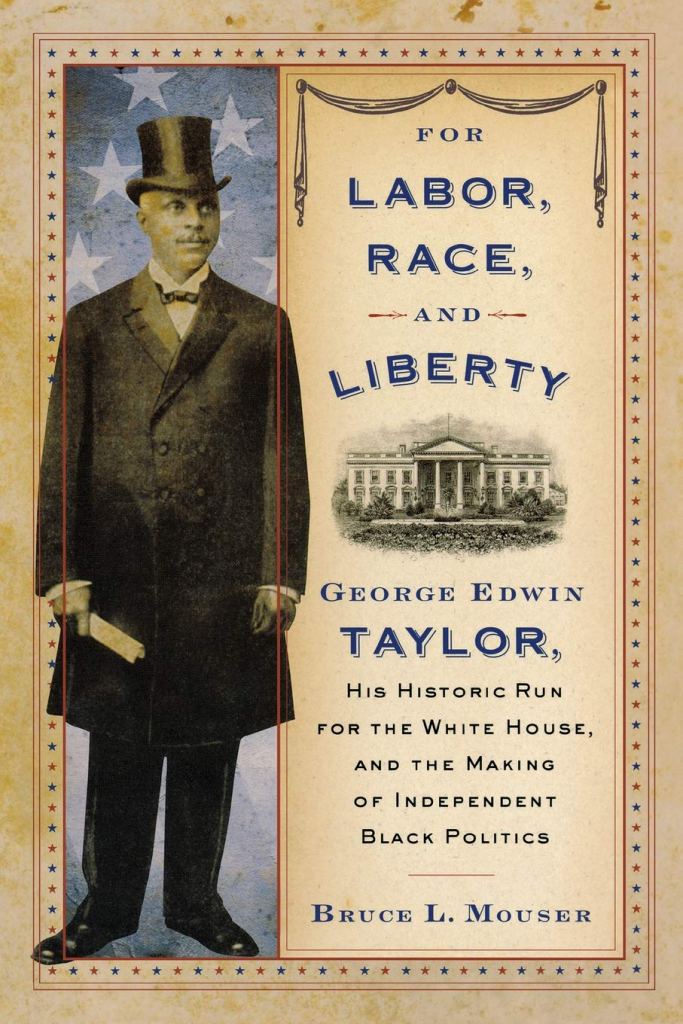

Find out more about the untold presidential run and more background on Black American politics in Bruce Mouser’s George Edwin Taylor, His Historic Run for the White House, and the Making of Independent Black Politics.

Read more about the book at the University of Wisconsin Press here.