All of the money in California might not have been enough to buy freedom for black Americans still enslaved and oppressed in the mid-to-late 1800s.

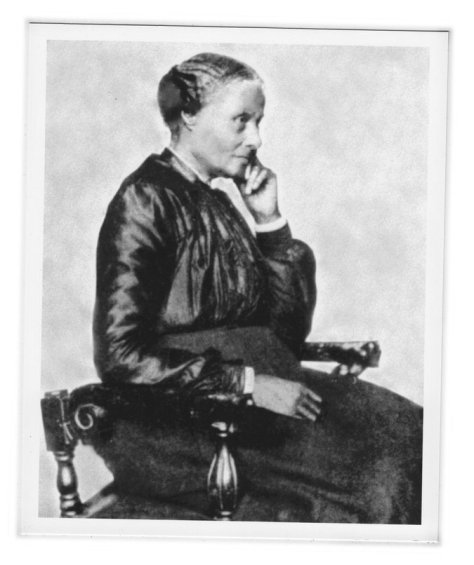

But free woman Mary Ellen Pleasant sure had enough to try.

Through an early life enshrouded in mystery and speculation, by the 1840s, a twenty-something Mary Ellen was coming into her own and creating her story, both literally and figuratively. Mary Ellen and her first husband James, both born from mixed-raced parents, could easily pass for white, but rather than benefit selfishly, they put themselves at risk freeing the enslaved. With the fortune James inherited from his white father, he and his “white” wife financed all manner of slave escapes – purchasing their deeds only to release them later, funding their travels along the Underground Railroad, and even providing shelter in the couple’s own home, a monstrous Virginia plantation with no staff because they’d all been set free.

When James died only 4 years after they were married, Mary Ellen embraced her newfound freedom, living her life in a way that only a single woman with light skin, lots of money, and a little backbone could. She and James had been rebellious, but Mary Ellen became an unrepentant renegade who preferred to dress in disguise and concoct elaborate back stories that allowed her to “steal” slaves right off the plantation. Her brilliant surprise attacks were the stuff of legend, but after 4 years of these ruses, she was infamous among southern plantation owners and had to make an escape of her own.

Slowly moving west in the direction of growing cities and eventually remarrying along the way, Mary Ellen was soon forced to pick up the pace by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Although she’d never technically been a slave (Massachusetts was a free state when she lived there as an indentured child servant instead), she also didn’t have the necessary papers to prove her freedom should anyone question her skin color and lineage. In a stroke of extraordinary luck, the free state of California was in the infancy of a Gold Rush and she had an eye on growing her fortunes. So with all of her money and her moxie, Mary Ellen landed in San Francisco, where she only became an even more formidable woman.

Gliding effortlessly between both white and black communities, Mary Ellen amassed millions. When she arrived in San Francisco, surveillance was her top priority. A brilliantly clever and well-educated woman, she relied on her domestic skills and society’s traditional gender roles to blend into the background of the upper-crust homes and restaurants she worked, knowing that no man would pay much attention to a servant woman, white or black, while discussing important financial business.

Her eavesdropping paid off extravagantly, granting her insider information on precious metals, natural resources and the stock market. Though she had to combine her investments with that of a white partner, since women – especially those masquerading as white – still didn’t have full property or financial rights, Mary Ellen’s savvy made them both rich to the tune of $30 million ($327 million today).

But Mary Ellen wasn’t the only transplant growing wealthy from California’s bounty. Southern slaveowners were migrating too, and though California was a free state, that didn’t apply to those who came as slaves. Her riches were propelling her rapid rise in San Francisco society, but Mary Ellen couldn’t overlook those who didn’t have the luxury of freedom she enjoyed.

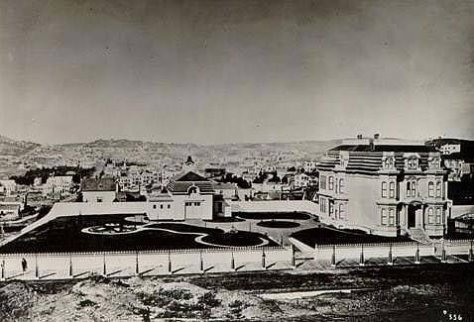

Instead, she used her money and power to take her abolition efforts to the next level: California law. When black citizens were discriminated against on San Francisco’s trolleys, she sued on their behalf, winning multiple cases against the city and the state over the course of the 1860s. Forbidden from testifying in California courts, black defendants often found themselves robbed of any chance of a fair trial, an injustice that Mary Ellen saw to in 1863, successfully repealing the law. Those who needed the means to escape could rely on her to front the money, transportation, food and any other necessities. She was so beloved among the black citizens of California that they soon called her home “The Black City Hall.”

When Mary Ellen’s white partner suffered an untimely death, all of that began to change. His wife ran a full-page smear campaign on Mary Ellen in the San Francisco Chronicle that destroyed what was left of her fast-crumbling reputation. After the Civil War and free from any fear of retribution (or so she thought), Mary Ellen stunned all of San Francisco when she submitted her census documents with an extravagant checkmark through the box labeled “black.” Racist rumors circulated about voodoo and black magic being the source of her wealth and social graces, and soon, unable to defend against the crushing public opinion or to distinguish her finances from her partner’s, she was left destitute and living with friends, where she died in 1904 at the age of 90.

As civil rights were won though, the details of Mary Ellen’s philanthropic and strategic impacts on black communities nationwide finally began to be revealed. All of her efforts in aiding the black people of California came to light, but on her deathbed, Mary Ellen still had one more secret to share with the world. When abolitionist John Brown – famous for the 1859 rebellion in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia where he and a small group of enslaved men stormed a confederate arsenal – was captured & hanged, a coded letter was found crumpled in his front pocket. “The ax is laid at the foot of the tree. When the first blow is struck, there will be more money to help,” it read. It was she who’d written that note, Mary Ellen revealed, and the “more money” she’d promised was in addition to the already $30,000 invested in Brown’s cause, just shy of $90K by today’s standards.

Her life of covert deeds now public knowledge and the record of her reputation set straight, the woman who once presided over “Black City Hall” and defiantly told those who tried to deter her she’d “rather be a corpse than a coward” is now known to all as “The Mother of California Civil Rights” and the “Harriet Tubman of the California Underground.”

”Mary Ellen Pleasant Memorial Park 1814 – 1904

Mother of Civil Rights in California

She supported the Western Terminus of the Underground Railway for fugitive slaves 1850-1865. This legendary pioneer once lived on this site and planted these six trees.

Placed by the San Francisco African American Historical and Cultural Society.”

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

The New York Times briefly chronicled Mary Ellen’s dramatic and eventful life in their “Overlooked” series.

Read more about Mary Ellen’s powerful sway in San Francisco and the wild scandals that led to her downfall in the Paris Review.