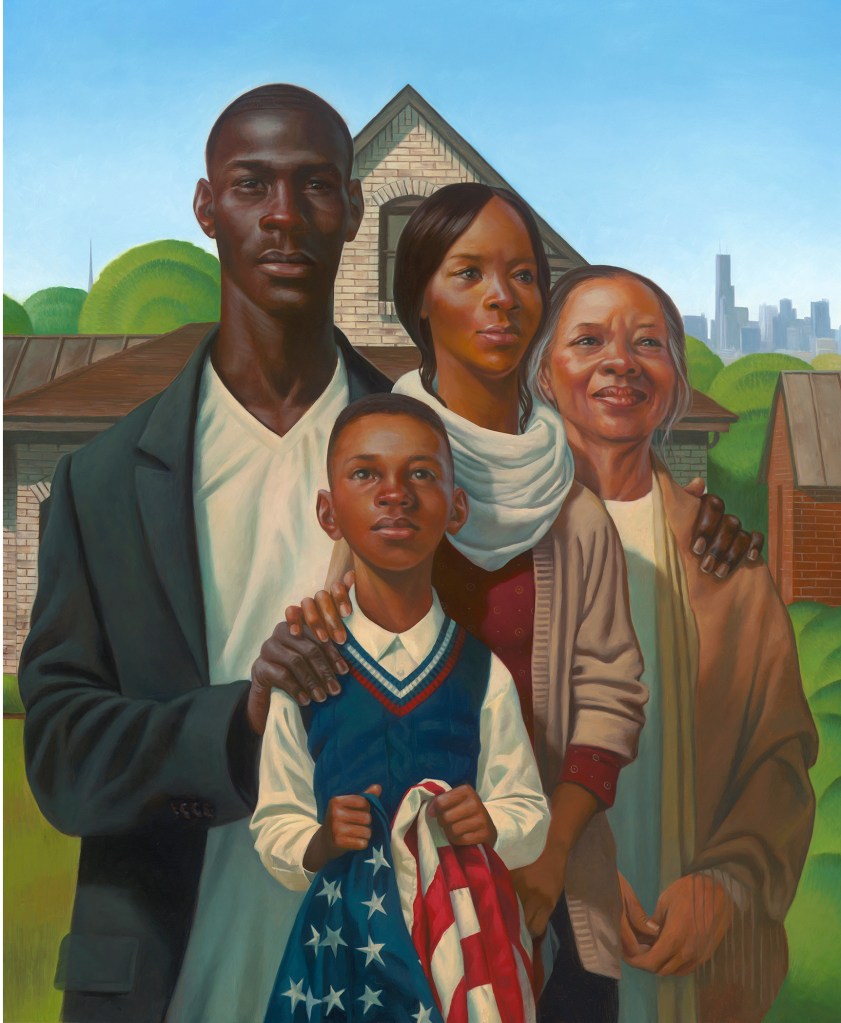

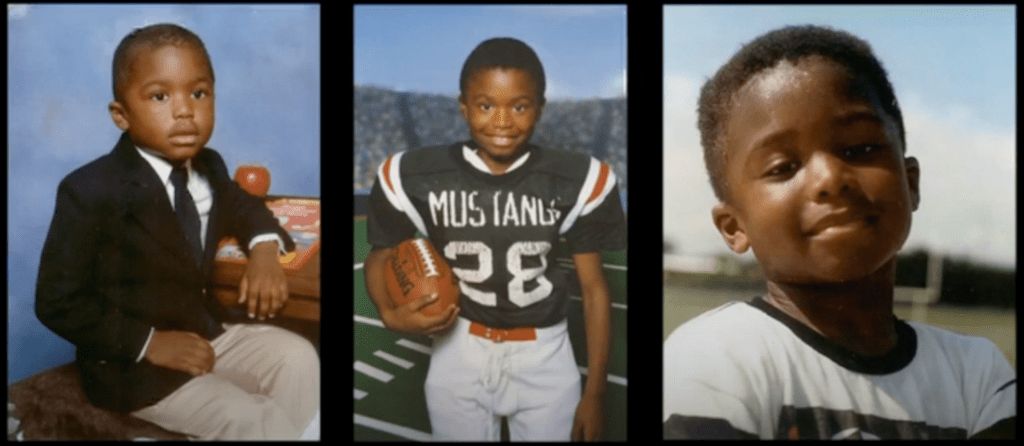

Scouting is in Kendall Jackson’s blood.

Her mother, Kellauna Mack, is a scoutmaster, an assistant scoutmaster, and an executive with the Scouts’ Pathway to Adventure Council.

Kendall’s brother Kenneth earned the rank of Eagle Scout way back in 2011.

The Girl Scouts Gold Award is their organization’s equivalent to Eagle Scout, and many say its requirements are actually more difficult to meet.

But I bet you still didn’t know what it was called until you read it just now.

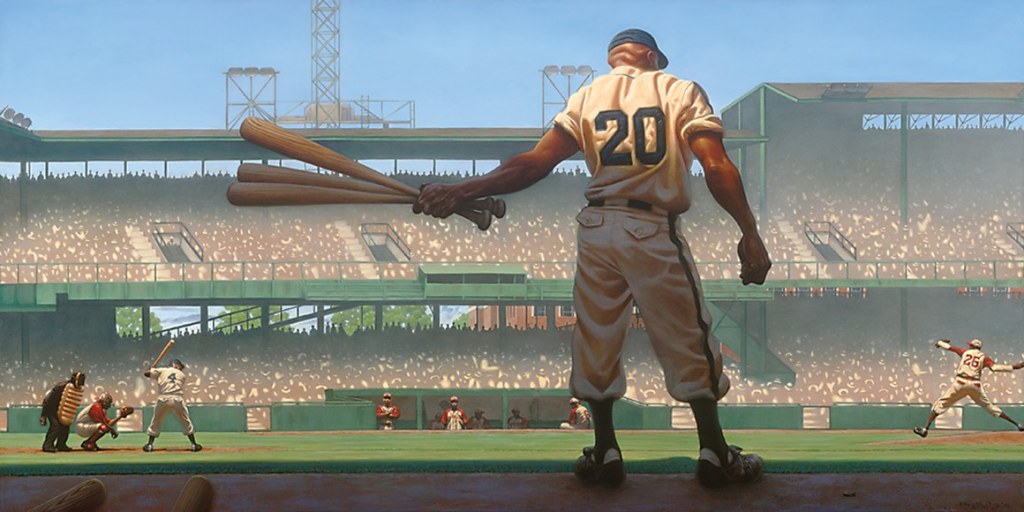

The rank of Eagle Scout is recognized by most Americans as one of the highest honors a minor can receive. In 2019, only 8% of eligible scouts earned Eagle, and since the inception of the Eagle Scout badge in 1912, only around 2% of scouts in Boy Scouts of America history have earned it.

It’s kind of a big deal.

And until February 1, 2019, it was a big deal Kendall Jackson wouldn’t get to have a part in.

But that was the day the Boy Scouts of America became Scouts BSA, opening its ranks to girls. Kendall was 15, and most Boy Scouts join their troops at around 10 or 11, earning their Eagle by 18. Eagle Scout badges are designed to be a process, requiring 7 ranks, 21 merit badges, an Eagle Service Project, demonstration of leadership within one’s troop, participate in a Scoutmaster conference and complete a board of review. Kendall had a lot of catching up to do, and wasted no time doing it.

To be fair, she did have a bit of a leg up. “I had picked up certain skills, like learning the Scout Oath and the Scout Law, I had been saying it since I could talk,” she said.

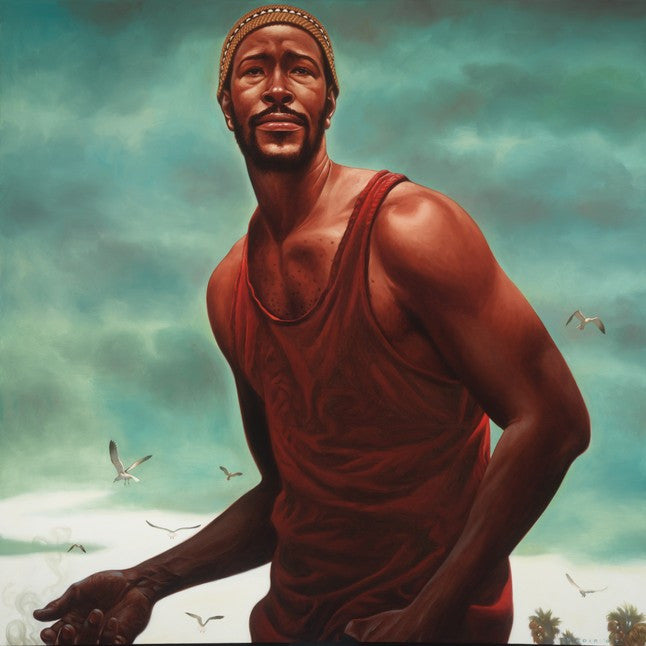

Seems that it all stuck because in 2021, just two years after the Boy Scouts of America admitted girls, Kendall was among their inaugural class of 1,000 earning the title of Eagle Scout. But that’s not all. She also earned the honor of becoming the United States FIRST African-American Eagle Scout, among 21 other African-American girls in the thousand.

Needless to say, Kellauna was over the moon. And probably all of her ancestors with her.

Backpacker Magazine says that “When the BSA began allowing young women to join its programs, it faced criticism from those who believed that girls like Jackson would be better served by girls-specific programs and that the organization was not equipped to accommodate female scouts.”

That language sounds familiar.

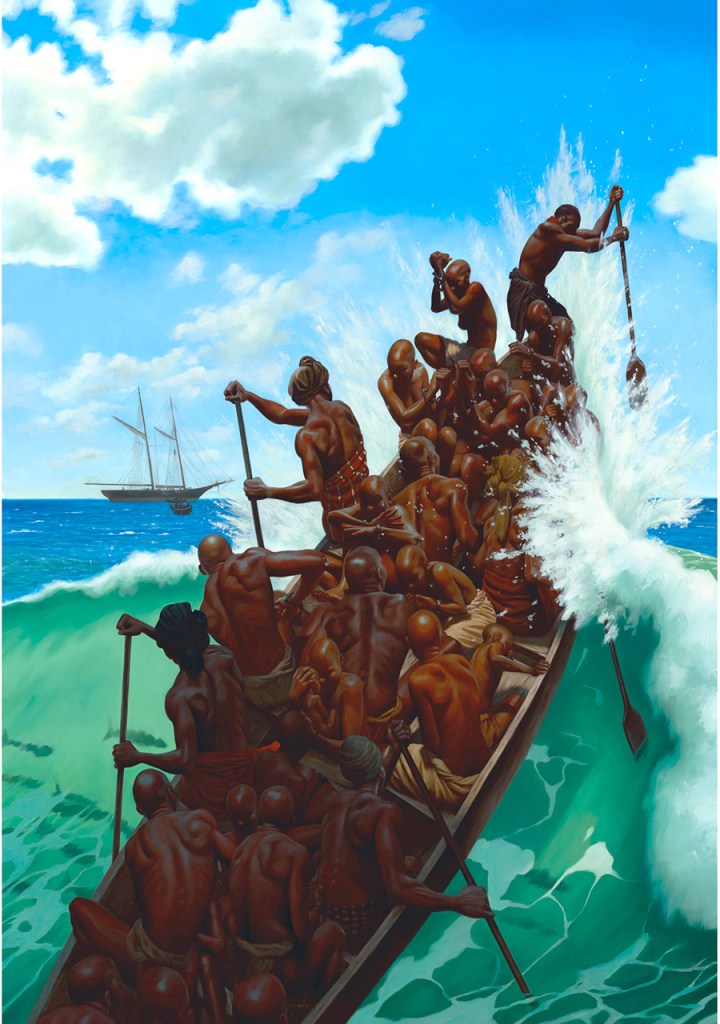

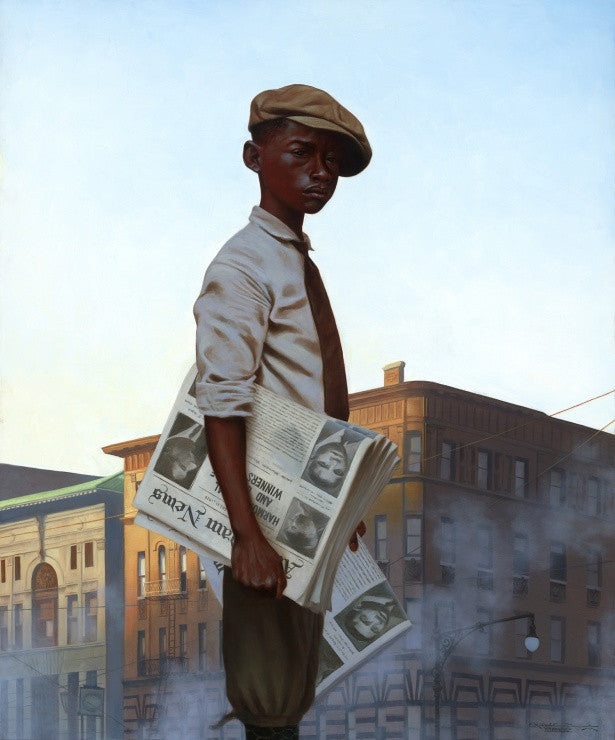

Though the first African-American troops were formed in the early 1910s, due to segregation, it wasn’t until the 1920’s, that the Boy Scouts established “Project Outreach” as a recruitment effort. Project Outreach split its non-traditional (read: non-suburban, non-white) troops into categories: “feeble-minded, orphanages, settlements, and delinquent areas.” But let’s not mince words. The Boy Scouts of America categorized being Native, African, or Latino American alongside mental deficiency and homelessness.

That’s not necessarily a surprise if you know that one of the biggest financial supporters of the Boy Scouts was the Ku Klux Klan. When the Boy Scouts began to allow integration, but ultimately left those decisions up to the troops themselves, the KKK was so furious, they began attacking scouts of color.

The Girl Scouts didn’t make any landmark strides in integration either, according to Stacy A. Cordery, author of Juliette Gordon Low: The Remarkable Founder of the Girl Scouts. “Daisy Low had proclaimed in 1912 that she had ‘something important for the girls of Savannah and all America. […] It is safe to say that in 1912, at a time of virulent racism, neither Daisy Low nor those who authorized the constitution considered African-American girls to be part of the ‘all,'” she writes.

Of course, the BSA has had lots of very public struggles with inclusion, none more public than their 2000 Supreme Court case upholding their right to exclude LGBTQ scouts, a decision the Scout Council rescinded just 5 years later. The inclusion of women, especially Black women, as recipients of their highest award is monumental progress.

“I don’t think any of us really thought this day would come. To say I have made Black history is a blessing. It is very humbling,” Kendall said. “For me to be a part of that first class and say that I did it, I’m really proud of myself.”

Proud and prepared, that is.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Get a few more details of Kendall’s amazing story at the Chicago Tribune.

Kurt Banas of Wake Forest University writes for the the African-American Registry about what it meant to minorities to become a scout.

Scouting Magazine begins a conversation about the first Black troops and what they overcame to be included in an organization of distinction.

The Smithsonian Magazine details a short history of integration in the Girl Scouts and the African-American women who made it happen.

Browse the issue of Scout Life Magazine celebrating the journeys of BSA’s brand new Female Eagles.