In the wee hours of December 4, 1969, the residence at 2337 W. Monroe St. on Chicago’s West Side became an all-out war zone. The sounds of wooden doors and their frames erupting into splinters, drywall vaporizing behind shotgun blasts, and indistinguishable shouting over the bedlam tore through the stillness.

By the time the smoke cleared, 100 hot shell casings littered the home, 2 people were dead, and Illinois State Attorney Edward Hanrahan had a perfect explanation at the ready: “The immediate, violent and criminal reaction of the occupants in shooting at announced police officers emphasizes the extreme viciousness of the Black Panther Party. So does their refusal to cease firing at police officers when urged to do so several times.”

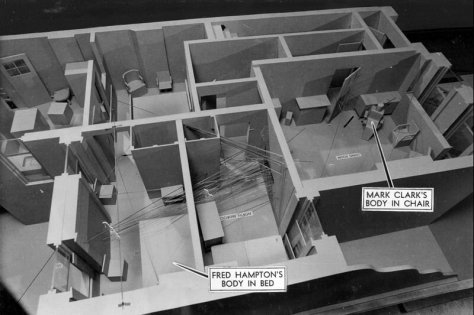

In an effort to appear transparent, Hanrahan and the Chicago Police Department staged reenactments of the raid on the Chicago Black Panther headquarters and even invited the press to see the aftermath inside. But when ballistic analysis was done, something didn’t add up.

Of the 100 shots fired, 99 were from Chicago Police. The single round fired by the Black Panthers had come from the gun of Panther security man Mark Clark as he was shot in the heart, involuntarily triggered when he fell dead from his post.

Ballistics also corroborated the story told by five other surviving occupants — one of the deceased hadn’t been killed in the onslaught of gunfire at all. He’d been dragged from bed with serious but non-critical injuries, and then fired upon, killed by two parallel, point-blank gunshots to the head.

Witnesses overheard the conversation between officers in another room:

“Is he dead?… Bring him out.”

“He’s barely alive.”

“He’ll make it.”

Suddenly and unexpectedly, two more shots rang out.

“Well, he’s good and dead now.”

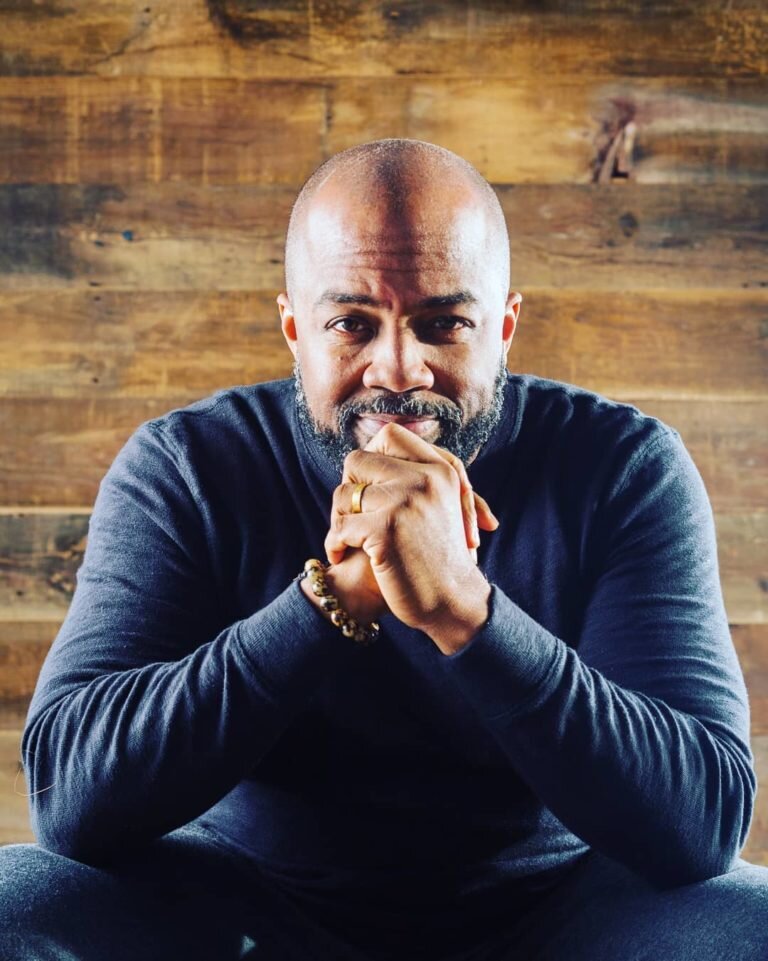

HE was Fred Hampton, 21-year-old chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party, and HE had just been assassinated by the Chicago Police Department and the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Fred Hampton was a rising star in the Black Panther Party. The warm tone and upbeat tempo of his voice made people lean in to listen more closely, and the anti-establishment message he delivered was only magnified by the charisma and congeniality he demonstrated among people of all races.

He first forced the government’s hand when, concerned that inner-city children couldn’t focus on education with empty stomachs, Fred introduced free lunch programs in several predominantly black schools. Ashamed and hoping to quell growing support for the Panthers, the local and federal government implemented their own free lunch programs for the very first time. When the neighborhood’s black children were dying from a genetic epidemic, Fred opened clinics specializing in tests for sickle cell disease. Soon after, government clinics began providing those same tests in their own clinics as well. Even warring Chicago gangs came to a tense but meaningful cease-fire with the help of Fred’s mediation, but when Fred’s leadership and organization skills began crossing racial lines, the FBI, under the directive of J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO, enacted their plan to “destroy, discredit, disrupt the activities of the Black Panther Party by any means necessary and prevent the rise of a Black Messiah.”

In one of the galvanizing speeches that gave the FBI particular concern about Fred’s ability to “unify and electrify the masses,” he said, “Black people need some peace. White people need some peace. And we are going to have to fight. We’re going to have to struggle. We’re going to have to struggle relentlessly to bring about some peace, because the people that we’re asking for peace, they are a bunch of megalomaniac warmongers, and they don’t even understand what peace means.” As the original founder of the “Rainbow Coalition,” Fred recognized the common goals of the Black Panthers, Puerto Rican Young Lords, and Appalachian Young Patriots sought for each of their respective communities, and unified the three groups to champion the disenfranchised of all races, threatening an imbalance in power that had to be stopped.

The FBI planned a raid on Fred’s apartment and the Panther HQ under the guise of seizing illegal weapons, and recruited the Chicago PD who’d recently lost officers in a shootout with a lone Black Panther to do the dirty work. But too many inconsistencies and surviving witnesses, along with the police’s failure to secure the scene that allowed the public to walk right in to evaluate the crime scene for themselves quickly tanked law enforcement’s credibility. There was even evidence that Fred had been drugged, preventing him from resisting the confrontation and explaining why he was still in bed after what police and witnesses actually agreed was at least 5 straight minutes of gunfire. The “weapons stockpile” police claimed in justifying the raid turned out to be 19 guns and a few hundred rounds of ammo, all legal. Despite mounds of evidence contradicting law enforcement, every officer involved was cleared of any wrongdoing. Though the state’s attorney had the nerve to bring charges of attempted murder of police and resisting arrest against the survivors of the “Massacre on Monroe,” they too were found not guilty as the one shot fired by the Black Panthers came from the gun of a dead man.

Insistent upon accountability for Fred’s death, which still hadn’t been adequately explained by any theory presented on behalf of either the FBI or Chicago PD, his family and the survivors opened a federal civil rights case. In 1983, almost 15 years after Fred’s death, despite the drama of continued cover-ups from judges involved in the case, a failed attempt by the FBI to force the plaintiffs into paying thousands of dollars in labor and printing fees for evidence they didn’t want to turn over, an eventual FBI whistleblower confession, and repeated appeals, the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals decided in the Hamptons & Panthers favor. Federal, state and local law enforcement agencies took equal financial responsibility for Fred Hampton’s death and granted the family a combined $1.85 million settlement.

But the damage was done. Though they hadn’t been successful in keeping it quiet, the goals of COINTELPRO and politicians on the state and local levels had been accomplished. Fred Hampton was dead, the alliances he’d fostered were effectively dissolved, and their smear campaign had played out long enough that in the public eye, the Black Panthers were a violent, racist threat suppressed by peace-keeping law enforcement agencies.

Chi-Town knows the truth, though. In addition to several landmarks around the West Side named after him, December 4th is recognized as Fred Hampton Day according to a resolution that he “made his mark in Chicago history not so much by his death as by the heroic efforts of his life and by his goals of empowering the most oppressed sector of Chicago’s Black community, bringing people into political life through participation in their own freedom fighting organization.”

It’s a fitting tribute for one of the most galvanizing figures of the Civil Rights Movement who once asked, “Why don’t you live for the people? Why don’t you struggle for the people? Why don’t you die for the people?” and then proceeded to inspire generations of people through a brave life and martyr’s death validating each and every word.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

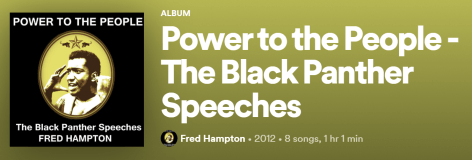

Listen to Fred’s charismatic speeches championing power to ALL of the people via Spotify.

The Chicago Tribune documented Fred’s life, death, and the continued COINTELPRO conspiracy throughout the Hampton v. Hanrahan federal civil rights case.

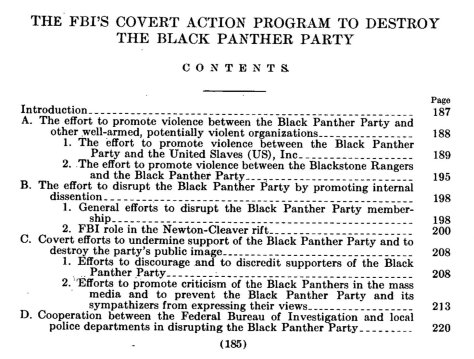

Read the 1976 Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s detailed investigative report that included a section titled “The FBI’s Covert Action Program To Destroy The Black Panther Party.”

The Committee report also details the FBI’s campaign against other black civil rights leadership, including but not limited to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the SNCC, the SCLC, and more “Black Nationalist Hate Groups.”