To an outsider, Kimberly and Jehvan Crompton seem like your run-of-the-mill mother and son. Jehvan is 15, introverted and loves science, English and video games. His mom describes herself as a “mommypreneur steady grinding.” Jehvan lives with his mom, sister and brother, and stays up too late. The Cromptons’ lives look pretty ordinary.

And until late 2019, they would have thought so too.

But that was the year that routine blood work Jehvan had done ahead of a foot surgery revealed news no mother with a symptom-free child is prepared for: his results showed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML).

CML is a cancer that starts in blood-forming cells of the bone marrow. It almost always occurs in adults, but Jehvan was that 1 in millions. And even worse, no one in his family was a full match.

As rare as childhood CML is, turns out Jehvan’s story isn’t very out of the ordinary at all.

“Right now, the make-up of the registry, it’s just overwhelmingly white,” according to reps at Be the Match, the national marrow registry. While 77% of all white patients find a match within its records, only 23% of Black patients ever do. (Notice that number adds up to 100%, so donor rates from other racial segments–along with the likelihood of donees finding a match–is infinitesimal.)

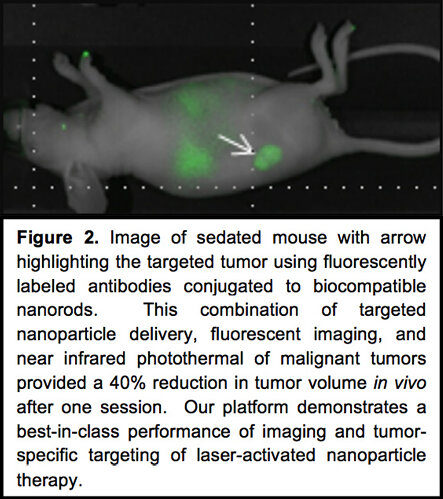

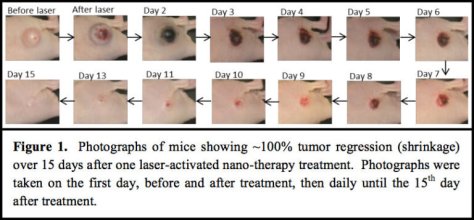

Aside from the many structural and social obstacles preventing Black patients from finding a match, there’s a genetic variable too. “Overall, blood cancers tend to be less common among African-American populations, but distinctly, multiple myeloma is the one blood cancer that’s seen at two times as high a rate in African Americans compared to other ethnicities,” Dr. Adrienne Phillips, medical oncologist at Weill Cornell Medicine says. Other blood diseases like sickle-cell also disproportionately affect Black and Hispanic patients, too often resulting in preventable deaths simply because these patients don’t have the same visibility and their cancers don’t have the same awareness or organizational support as the other 77%.

So instead of waiting for the odds to fall in Jehvan’s favor, Kimberly decided to put her own numbers up against CML. “I believe this was God’s plan. But I have to do my work,” she said.

Her goal was 200. If she could get just 200 more Black donors on the Be The Match registry, her son’s chances of matching one would increase dramatically.

As of January 2021, Kimberly’s campaign alone has brought 13,000 fully registered donors to Be The Match. That number has no doubtedly continued to skyrocket.

Thousands, but still no match for the one patient who mattered most.

But Jehvan was already prepared for that outcome: “Even if I don’t get a match out of the 13,000 or more that come up, it’ll just be great to see that everyone else got a match,”

Her son’s optimism and selflessness only made the doctors’ next call that much harder to hear: Jehvan’s leukemia had become resistant to chemotherapy, the cancer cells were multiplying and a blood stem-cell transplant was his only hope.

“It’s like getting hit by a dump truck and then that dump truck hitting you again and going back over you again,” Kimberly said.

The news forced them to resort to a half-match, which was just as likely to lead to Jehvan’s death as it was to his cure. The closest half-match doctors could find turned out to be Jehvan’s adult half brother, with whom he “didn’t have much of a relationship before this happened,” Jehvan said.

“This” is a successful transplant in March 2021, leaving Jehvan cancer-free.

He says his relationship with his brother is “getting better and better by the day,” especially now that he has so many more ahead.

And 13,000 more people of color on the bone marrow registry are getting that same opportunity now, all thanks to one “ordinary” little boy.

“At first I didn’t think my story was so much different than anyone else’s, but apparently people think otherwise. So, I guess I’m very special,” Jehvan said.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Read more of Kimberly & Jehvan’s story and the science about how race affects blood cancers at SurvivorNet.

Bakersfield news station 23ABC followed Jehvan from half-match to cancer-free, and as its the most visible and vulnerable I’ve seen a Black family fighting cancer represented in the media in some time, I found both articles worthy of sharing.