Dr. Feranmi Okanlami experiences discrimination every single day.

It’s not necessarily because he’s a Black man, but because he’s a Black man in a wheelchair.

“Until I started to live life on the other side of the stethoscope… I did not realize how ableist our world was, how inaccessible the world was and how I was unintentionally complicit to this world,” he told Good Morning America.

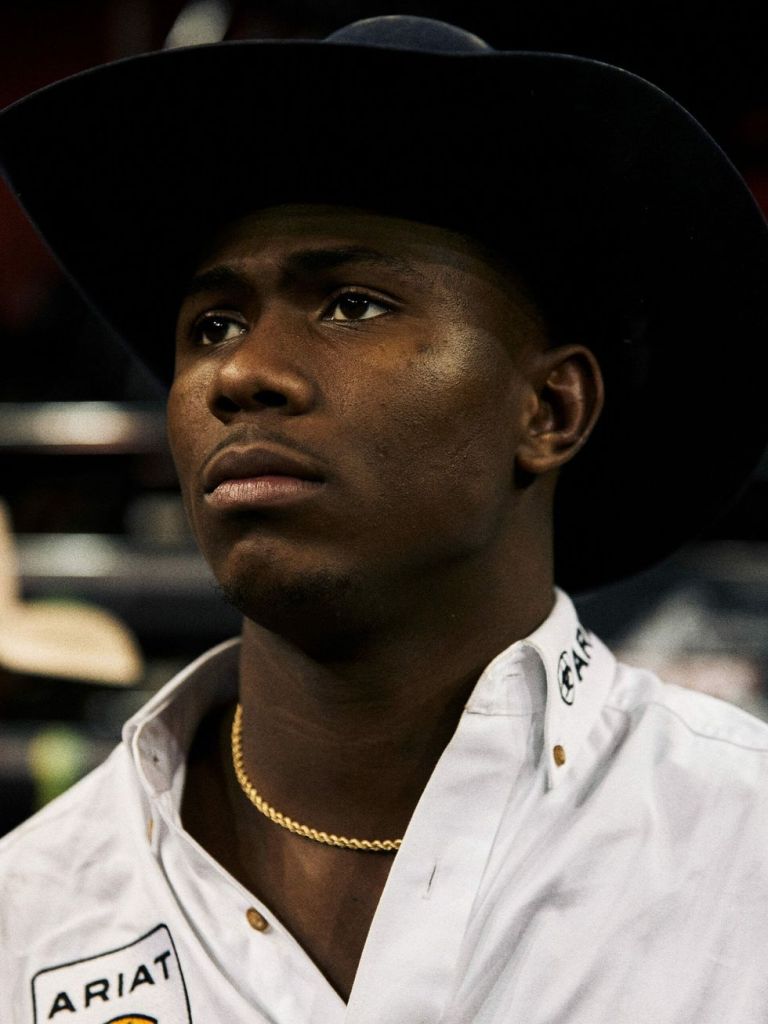

Dr. O, as he’s nicknamed, didn’t always use a chair. Born in Nigeria and raised in Indiana, he’d graduated Stanford as an All-American track star and captain of his team, then medical school at Michigan, and worked as a third-year resident in orthopedic surgery at Connecticut’s Yale New Haven Hospital. Dr. O was on a brilliant path until a 2013 Fourth of July accident changed his mode of transportation, and then some.

“I jumped into the pool,” he said. “I didn’t do a backflip or anything like that. There was no diving board, but I hit either the ground or the side of the pool or someone’s leg. I can’t be completely sure, but immediately I was unable to move anything from my chest down.”

Most people with his cervical injury “are not expected to ever be able to walk or stand,” his mother Bunmi said.

Dr. O is a man with higher expectations.

“I have an interesting intersection of science and faith, such that even if doctors had said I would never walk again, I wasn’t going to let that limit what I hoped for my recovery,” he said. “I know there is so much we don’t know about spinal cord injury, and I know the Lord can work miracles.”

Two months and countless hours of physical therapy later, Dr. O gained the mobility to extend his leg. With time, he gained something else too: a Master’s degree in Engineering, Science and Technology Entrepreneurship from the University of Notre Dame. “[I was] looking for something I could do to stimulate myself intellectually while I was working myself physically,” he said. Dr. O even finished his medical residency.

After his injury, he accomplished everything he’d set out to do as an able-bodied person, and then some. But Dr. O also found that the outside world put up unnecessary physical barriers every step of the way.

He learned that medical school admissions require physical qualifications that prevent those with certain disabilities from even applying. That’s just one reason why only 2.7% of doctors identify as disabled compared to more than 20% nationwide.

He realized that there have been more advancements in high-end self-driving cars than in making standard vehicles more accessible.

And as an athlete in a wheelchair, finding a good pick-up basketball game was near impossible.

Dr. O suddenly had invaluable insight into the lives of so many of his patients. “I have one foot in one world and one wheelchair wheel in another,” he said. Disabled patients can better relate to disabled doctors, of course. But think of how other patients like the pregnant woman on bedrest, the aging person beginning to lose mobility, even the child with a broken limb might benefit from a doctor who’s compassionately vulnerable.

“How are we supposed to be able to talk to patients and tell them it’s okay, that life can still go on, while creating a culture where the providers themselves must come across as immune to the same ailments we treat our patients for?” he wondered. “My goal is trying to demonstrate to them, through one lens of disability, that we are all going to have our difficulties and our struggles and that’s what makes you human, and believe it or not, sometimes your patients will value seeing the human in you.”

Dr. O knew that the human experiences he’d faced as a newly disabled person weren’t unique to him. So he set about changing those experiences for the better.

Where other doctors rightfully fear being judged for their disabilities, Dr. O used his experience as a spinal trauma patient to help develop a device that makes spinal screw placements more accurate and efficient.

He uses his platform and privilege to be vocal about how airlines treat wheelchairs, reminding PBS that “People don’t think that this is a serious concern and it’s just a matter of finding space to put your wheelchair, like not having enough space for your luggage in the airplane. They miss the fact that this is individuals’ lives that are at stake.

And as Director of Adaptive Sports and Fitness at the University of Michigan, he’s doing his part to ensure that people with disabilities have the same access to physical and outdoor activities that others do.

“Too often, we are judged by what we cannot do, rather than what we can,” he said, speaking to his goal of “Disabusing Disability” and creating a world where equal access and diversity truly extend to everyone.

Dr. O’s dream is for Michigan to combine its talents in medicine, athletics and science to become the premier home for accessible sporting facilities, drawing Paralympic and other elite level athletes from all over the world.

He’s gained so much traction that others are stepping up to help make his dream a reality for countless more. Just last year, the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation, whose mission of “changing the world for those living with spinal cord injuries and the definition of what is possible” aligns perfectly with Dr. O’s, donated $1 million dollars to Michigan Adaptive Sports.

But he also recognizes that it doesn’t take millions to make a difference in medicine, just a change of attitude.

“It is not that every Black patient needs a Black doctor, nor that every patient with a disability needs a physician with a disability. Every patient deserves an empathetic doctor,” he said.

And he means EVERY patient. His work at Michigan has earned Dr. O a place on national boards like the Association of American Medical Colleges Steering Committee for Diversity and Inclusion, the National Medical Association’s Council on Medical Legislation, and even the White House Office for Health Equity and Inclusion.

They said he’d never walk again. Today, with assistive devices like his standing frame wheelchair, Dr. O can perform surgeries, stand before an audience, and yes, even walk. He’s working on running, but until then, catch him chasing disability discrimination out of medicine, and with a little luck, the world.

He’s faced worse odds.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Get more of Dr. O in GMA host Robin Roberts’s Facebook Watch series, “Thriver Thursday.”

Hear Dr. O and Dr. Lisa Iezzoni from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital discuss how “Medicine Is Failing Disabled Patients” at Science Friday.

Read more about how Dr. O and others practicing “seek to mend attitudes” in medicine.

Follow Dr. O’s journey on Instagram.