The Buffalo Soldiers have a deceptive name.

And I’m not talking about the “Buffalo” part.

Yes, reports do vary as to whether that nickname came from the heavy buffalo fur coats these Black regiments wore on the American frontier, or from their hair texture that seemed nearly identical to the buffalo’s.

It’s the “soldier” that reasonably implies that all these men did was fight.

From their establishment in 1866 to the last regiment’s formal service disbanding in 1951, their military contributions are too tremendous to count.

But their peaceful contributions here at home are absolutely stunning.

In fact, if you’ve ever been to ANY major national park west of the Mississippi, chances are you’ve walked directly in their footsteps and don’t even know it.

Yosemite, Yellowstone, Hawai’i Volcanoes, Klondike, and Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks simply would not exist without the Buffalo Soldiers’ relentless work.

And that’s still just a fraction of the trails they blazed across the United States.

Between 1866 and 1891 alone, the Buffalo Soldiers are documented at 250 sites across twelve different states.

One of the furthest is Hawaii, and its “highly challenging” 36-mile Mauna Loa Trail. 30 of those miles leading to the 13,681-foot summit were painstakingly carved out of solid lava by the Buffalo Soldiers with 12-pound hammers as their only tools.

Further north in California, Brigadier General Charles Young—who later became the first Black U.S. national park superintendent and the highest ranking Black Army officer until he died in 1922—led his company in clearing a road into Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Park, allowing public citizens access to the giant trees for the first time ever.

When leadership suggested naming a sequoia for then-Colonel Young, he refused, humbly requesting the tree be named for Booker T. Washington instead. If sentiments were the same in 20 years, he said, only then might he accept the honor. Spoiler alert…

But that wasn’t the only big work the Buffalo Soldiers took on in California. If you’ve ever taken the trail up nearby Mt. Whitney, the highest peak in the lower 48, you got it. Buffalo Soldiers.

Among the first people to survey and create trails through the land that would become Yellowstone National Park, the nine men of the 25th Infantry bicycled from Missoula, MT to Yellowstone, crossing the Continental Divide twice over a 800-mile round trip. Since Yellowstone was still a largely uncharted place, there were no permanent accommodations. By necessity, these men carried over 100 pounds of gear, munitions and provisions, all on their bikes.

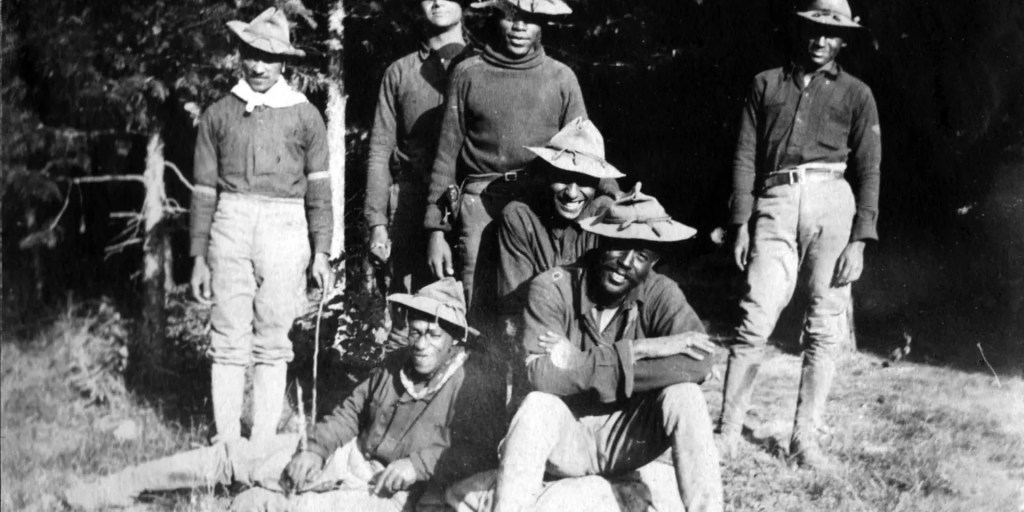

Compared to those assignments, Yosemite’s pristine landscape was a “cavalryman’s paradise” actively sought out by soldiers from all corners of the States. And yet, to this day, Yosemite specifically names the Buffalo Soldiers as the “stars of its story” and “safeguards of its mountain cathedrals.”

All of these trailblazing acts of service by the Buffalo Soldiers were before the National Park System was created. So more than just pioneers and explorers, the U.S. Army served as the country’s original Park Rangers.

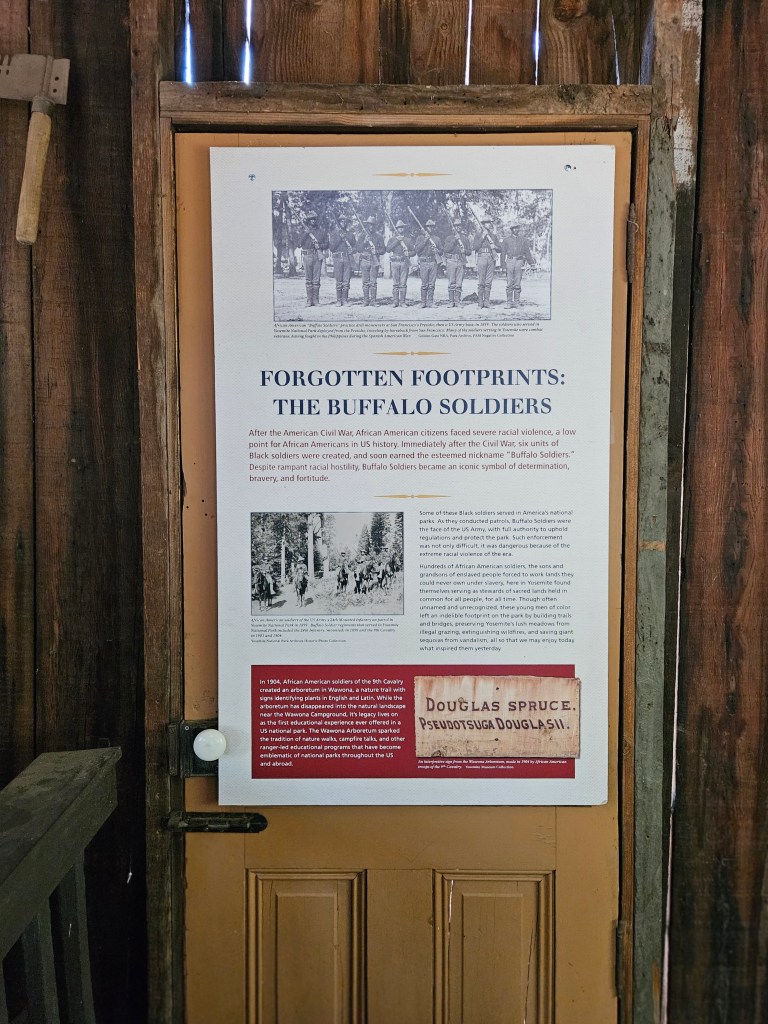

In Yosemite, that service was especially vital as the park was especially vulnerable to all sorts of dangers like poachers, wildfires and overgrazing. The Buffalo Soldiers regularly patrolled against those dangers and were fully prepared to oppose them if necessary. When they weren’t protecting Yosemite’s borders, they built the Wawona Arboretum in 1903, and in the process, launched the U.S. National Parks’ first educational program, a cornerstone of the system today.

Now, if you’re paying attention, you might notice a theme. The Buffalo Soldiers were frequently sent to the most remote and rugged parts of the U.S. territories to forge new lands and protect them through military force if necessary. Aside from poachers, fires and livestock, the Army was almost certain to confront Indigenous People.

And Army leadership knew they had a secret advantage in the Buffalo Soldiers, because they’d learned it from some of the first U.S. pioneers, Meriwether Lewis & William Clark.

When native tribes encountered Lewis and Clark, it was frequently their curiosity or admiration of York, the expedition’s enslaved man, that gave those tribes any incentive to speak to white men at all.

It’d be naive to believe this didn’t influence the Buffalo Soldiers’ peacekeeping AND wartime assignments, where they were deployed against native Americans, the Spanish, Filipinos, and Mexicans among many others. Whether it was that they were expendable against other brown people, or that they unknowingly served as a shock tactic against them, the Buffalo Soldiers valiantly fought on behalf of the United States anyway.

The Army enlisted fighters, but look closer and you’ll find the Buffalo Soldiers’ true legacy still growing along the most peaceful streams, under purple mountains, and so many more places that make America beautiful.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Listen in on Ranger Johnson’s historically based podcast “A Buffalo Soldier Speaks” here.

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture maintains an extensive Buffalo Soldiers collection here.

Learn more about their historic service at the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum.

Browse the beautifully crafted history of the Buffalo Soldiers maintained by Yosemite.

Explore the National Parks Service archive of the Buffalo Soldiers 85 year long impact on the foundation of the United States.

There’s still more about how and why the Buffalo Soldiers were the first national park rangers at History.com.