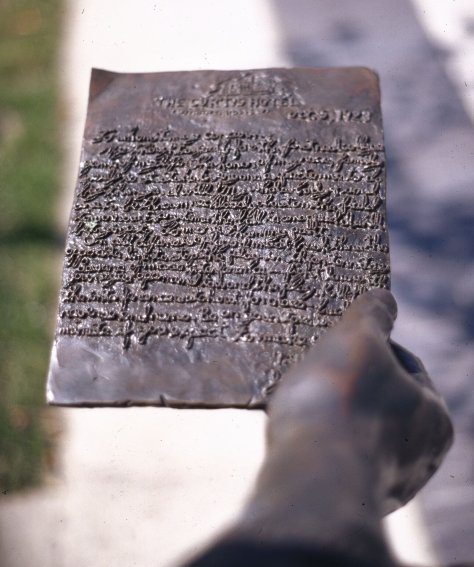

“My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life. The honor of my race, family, and self are at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will!”

In pointed, anxious cursive, Jack Trice took his innermost thoughts to the stationery of the Curtis Hotel in Minneapolis, Minnesota. After all, there was no one else for the 21-year-old to share his excitement, anticipation, and gameplan with. As Iowa State University’s only black player, the segregated accommodations at away games meant he ate dinner in an empty room, and unburdened his true feelings to the only person he could: himself. Once he’d claimed his victory on paper, he folded the letter, humbly tucked it inside his suit pocket and prepared for the game of his life.

My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life. The honor of my race, family, and self are at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body and soul are to be thrown recklessly about on the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped I will be trying to do more than my part. (supper) On all defensive plays, I must break through the opponents line at (sic) stop the play in their territory. Beware of mass interference, fight low with your eyes open and toward the play. Roll block the interference. Watch out for cross bucks and reverse end runs. Be on your toes every minute if you expect to make good. (meeting) 7:45

Jack

Three days later, that bright young life was lost. Jack Trice died on October 8, 1923 from injuries sustained in his second ever college varsity football game.

Back then, for a football player to be critically injured, or even die, wasn’t entirely out of the norm. Without the protection of pads, facemasks and other safety developments that came later, the game could be brutal. But in Jack’s case, there was another dynamic at play. In 1923, Iowa State was one of only 10 integrated major college football teams. On the field, the 215-pound tackle, who by all accounts was a quiet force who worked hard to succeed and blend in at Iowa State, couldn’t have stood out more to the University of Minnesota Gophers. Whether it was out of fear of his race, his indomitable blocking, or both, the opposing team focused their efforts on one man.

His teammate Johnny Behm reflected on the events that led to Jack’s untimely death, quite aptly capturing the conflicting feelings about what was at least a very public demise: “One person told me that nothing out of the ordinary happened. Another who saw it said it was murder.”

In just the second play of the game, Jack’s collarbone was broken, but he insisted on staying in. Toward the end of the third quarter, Jack was trampled by Minnesota linemen, and still only begrudgingly allowed himself to be carried off the field. He was treated and sent home to Ames with his team, where he finally succumbed to internal bleeding days later.

Despite “we’re sorry” chants from Minnesota’s fans as the Cyclones hauled Jack’s broken body off the field, that game’s events led to Iowa State’s refusal to play Minnesota again for 66 years in protest of Trice’s mistreatment on the Gophers’ home field. Jack’s integrity and tenacity so inspired Iowa State fans that they launched a 24-year-long campaign to officially name their football stadium in his honor, making it the only NCAA Football Division I stadium to bear the name of a black man.

One account surmised that Jack was so determined to stay on the field in spite of his fateful injuries because he hadn’t achieved what he set out to do in his letter, which was to “make good” on his promises to himself. But by 1930, just 7 years after Jack’s death, four more Division I teams were integrated, and 42 years later, every major college football program in the United States had a black player. Though he didn’t survive to see it, Jack Trice’s legacy was to open the door for thousands of others to make good on his handwritten promises forever.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

See more Jack Trice images and history at the Iowa State Digital Archives.