By the time the United States purchased the Virgin Islands in 1917, slavery had technically been abolished in most of the colonized world.

But freedom had not come easily to the Virgin Islands, and the United States was buying one of only two territories in the Caribbean that had won that freedom through a fight. It all started when the enslaved people of Frederiksted, one of St. Croix’s most significant cities, got sick and tired of being sick and tired.

In 1847, Danish Governor Peter von Scholten put their freedom on a timetable, presenting a twelve-year plan to give every Crucian (the people of St. Croix) their independence.

Nobody was having that.

Sugar cane was one of the island’s primary exports, and without it, a whole lot of (white) people would go bankrupt. On the other hand, the enslaved saw no reason to wait for what was rightfully theirs.

A stand-off was brewing on St. Croix. After the Haitian Revolution in the early 1800s claimed nearly 500,000 lives, required a military response from Britain, France and Spain, and brought Haitian slave labor to an end, rebellion lingered in the Caribbean air.

The first match lit in St. Croix was struck just a year after the governor’s abolition law.

St. Croix’s enslaved already had a few key learnings on uprising strategy in the islands. First, as they were expected to provide every bit of labor, they far outnumbered those who kept them in chains. Second, though they’re surrounded by water, islands are particularly vulnerable to fire. And third, any help to quell an uprising would have to come from miles, if not, entire oceans away.

With that knowledge, and led by skilled worker John Gottlieb, 8,000 Black Crucians stormed Fort Frederik, and demanded their freedom that day, else they’d set all this stuff on fire.

And they got it.

Sort of. Upon receiving the governor’s abolition law, the plantation owners got busy finding loopholes, and they were ready. They presented these newly freed people with contracts, a reasonable expectation upon being freed, right? Except that per these contracts, a worker and their family were obligated to work the plantation they’d signed with for one year. During that year, they could make no complaint on wages, treatment, working conditions or any other labor concern, until “Contract Day.” On that day, and only that day, could contracts be amended.

And had everything been on the up and up, it probably would have been a pretty decent outcome.

But everything was not on the up and up. You’d think the Danes would have learned.

Their newly contracted labor force was not paid a living wage, and most found themselves in worse condition than they had been as slaves. Because the workers were no longer their property, the plantation owners had no interest in ensuring their well-being. Without money for the basic necessities or even medical treatment, Black citizens suffered, but were still expected to serve as the backbone of the labor force. Black women in particular were bearing the full weight of an unjust society. They worked brutal jobs and long hours for insufficient wages, cared for sick and injured husbands and children, foraged food to feed their families, and so many more hardships exacerbated by Danish oppression that they had finally had enough.

So, on Contract Day – October 1, 1878 – THIRTY whole years after the abolition law that was supposed to make them fully free, WOMEN led Black Crucians to demand their grievances be heard.

They were not.

Instead, Danish troops escalated the situation by firing on the crowd. But still massively outnumbered, they were forced to retreat into the walls of the very same fort they’d defended 3 decades before.

With Danish troops self-barricaded and all other Danish colonialists too afraid to intervene, Mary Thomas, Agnes Salomon, Mathilda McBean and Susanna Abrahamson made good on the Black Crucians’ original threat.

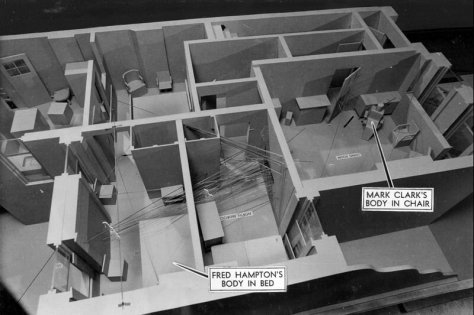

Cane fields, plantations, mills, corrupt government buildings… nothing was spared the torch. When the smoke cleared, only 2 soldiers, 1 plantation owner, and less than 100 Black Crucians were dead. 400 were arrested. But nearly 900 acres of Frederiksted had burned to ash.

12 people were sentenced to death for their part in the 1878 St. Croix uprising known to the locals as the Fyah Bun. But Queens Mary, Agnes, Mathilda, and Susanna were not among them. Executing them as martyrs might have incited another uprising, but imprisoning them on the island was equally dangerous and unpredictable. Instead, all four women were extradited to Denmark, and sentenced to life in a hard labor prison.

It wasn’t immediate, but the Black Crucians DID get true freedom, and the scars they left in their fight for it are still visible all over Frederiksted.

“The young [Danish] people ask ‘Why don’t you take care of the ruins? You should rebuild some of the places. There’s so much lost history,’” Crucian historian Frandelle Gerard recalls. “I say to them, ‘Honey, they were burned on purpose! And they will never be rebuilt!’”

But in 2018, something else was. In Copenhagen. Artists La Vaughn Belle and Jeannette Ehlers, Black women from St. Croix and Denmark respectively, erected their massive 23 foot statue, “I Am Queen Mary,” not far from where its subject was imprisoned and just outside the Danish West Indian Warehouse where imported sugar and rum produced by enslaved people was stored. “Queen Mary” is Copenhagen’s first public monument to a Black woman. She’s fashioned after a seated photograph of Black Panther Huey P. Newton, holding her torch and cane knife fast at hand, and serving as a towering reminder of Huey’s words “You can jail the revolutionary, but you can’t jail the revolution.”

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

The anniversary of John Gottlieb’s uprising is known as Freedom Day in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Read all about it on St. Croix’s tourism website.

Black Danes are preserving the history of the Fireburn and you can view their archive and more history of the Danish slave trade here.

Learn more about slavery in Danish Colonies like St. Croix at the Danish National Museum’s website.