From Atlanta where the players play to the drama of the LBC, and Brooklyn Zoo to 8 Mile Road too, there’s not a corner of this country that hasn’t been touched by hip-hop.

But when summer days driving 2 miles an hour so everybody sees you turn into nights with the sounds of street sweepers and AKs, and even where ya grandma stays carries consequences, one man is making it his mission to give ethnic communities better.

“We hear the lyrics in hip-hop, but the stories that they’re telling are a critique of the environment they live in, so when you hear someone talking about guns or drugs, instead of changing the station, we should be changing those environments,” says Mike Ford.

Mike’s two greatest loves are architecture and hip-hop. It’s an unlikely combination, but at its crossroads, he sees an opportunity to affect generations to come through design justice. It’s a principle that according to MIT Press “is led by marginalized communities and aims explicitly to challenge, rather than reproduce, structural inequalities.” Boiled down, design justice identifies the social, economic, environmental and political issues that exist in community spaces, and uses the community’s knowledge and insight to help solve them. When poor test scores lead to underfunded school districts, and eventually lower economic status or even incarceration, design justice practitioners might learn from moms that thin housing project walls mean kids can’t focus on their studies – solving potential lifelong pitfalls with one simple solution.

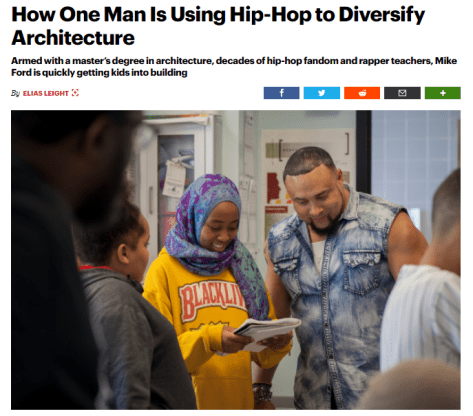

How the legends of hip-hop might have grown up writing different rhymes was a concept Mike was so invested in that instead of thinking about it, he decided to be about it, founding the Hip Hop Architecture Camp.

According to Mike, “The Hip Hop Architecture Camp® is a free, one week intensive experience, designed to introduce underrepresented youth to architecture, urban planning, creative place making and economic development through the lens of hip hop culture.” With the help of architects, urban planners, designers, community activists and hip hop artists, kids use professional drafting software and 3D models to build their own cities and communities “so that nobody has to tell those stories in their songs again.”

Aside from the change he hopes to bring to kids’ lives, Mike’s Hip Hop Architecture Camp serves another equally critical purpose, too. “Hip hop has always been the voice of the voiceless,” he says. “In architecture, less than 3% of the professionals are African American. Less than 1 in 5 architects identifies as a racial or ethnic minority, and black women comprise less than 1% of the field.” By giving kids their first introduction to architecture through hip hop, he’s introducing the field of architecture to them, too.

“I’m trying to show architects, planners, and designers that our profession is more than brick and mortar. We create incubators of culture,” Mike explains. “Even if someone is not a fan of hip-hop, or simply doesn’t like the culture, I challenge him or her to understand why it exists, and how our profession necessitated its birth through bad planning and housing practices.”

Take for example the Cross Bronx Expressway. Its construction on Manhattan Island in 1955, created a structural division and environmental nuisance that drove middle- and upper-class residents to build affluent communities and economic districts further south, but left people of color and the poverty-stricken isolated. Today, the Bronx is arguably considered the birthplace of hip hop, a detail that Mike knows isn’t a coincidence.

He regularly quotes NAS whose song “I Can” encourages kids to be – among other skilled professions – architects. Mike’s taking that song’s spirit and laying the foundation for the engineering, mathematical, imaginative, and critical thinking skills it takes to be successful in his field, as early as possible. After all, as an architect, he’s also familiar with the great communities of color like Greenwood in Tulsa and Black Bottom in Detroit, both long decimated. “I’m letting kids know we have a history of building spaces and places,” he contends.

For the 10-to-17-year-olds attending Mike’s Hip Hop Architecture Camp in dozens of cities nationwide, learning their history, analyzing their playlists and tinkering in models are more than just fun ways to spend a week. It’s what Mike hopes builds the right knowledge, experience and dedication to see to it that the people influenced by trap house environments can graduate to corner offices where they’re empowered to change them.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Host, attend or just learn more about a national Hip Hop Architecture Camp.

Check out Rolling Stone’s feature on Mike Ford & his camps.