Stonewall had a formidable security team, and her name was Stormé.

And though Marsha P. Johnson, another famous face at Stonewall, may not have participated as once believed, everybody agrees that Stormé DeLarverie was not only there on June 27, 1969—she got her lick in.

“She literally walked the streets of downtown Manhattan like a gay superhero,” her friend Lisa Cannistraci told the New York Times.

Well-known for her neighborhood patrols—and her gun permit—Stormé didn’t tolerate “ugliness” in her community. But that’s exactly what met her when she rushed to the chaotic raid at the Stonewall Inn.

“Move along, f****t,” NYPD spat at her.

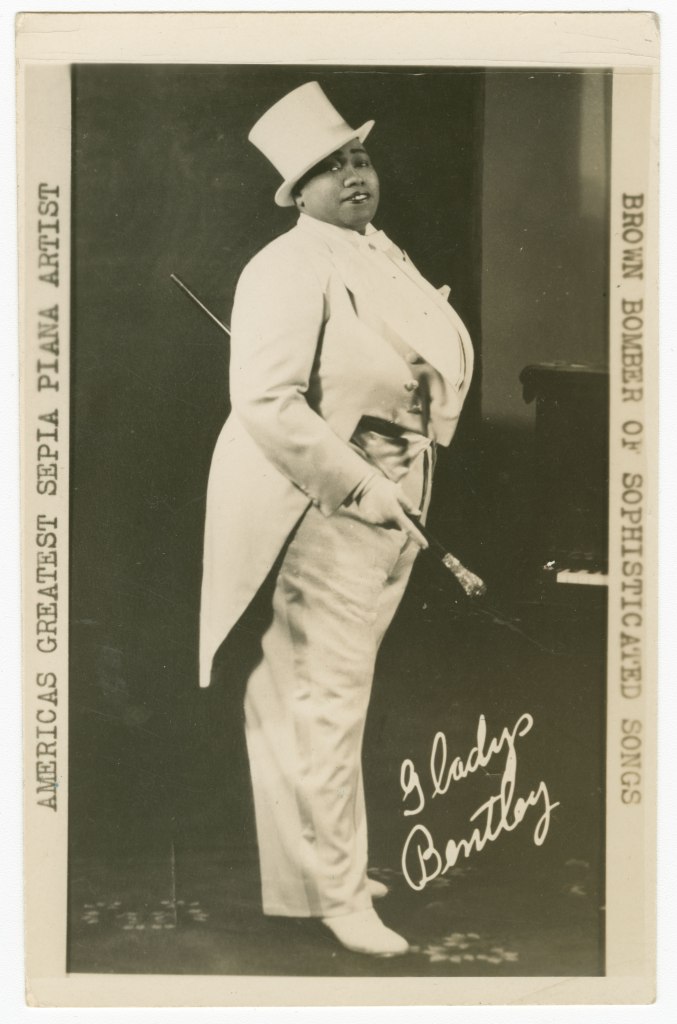

New York penal code prohibited cross-dressing, but police had to know someone was cross-dressing to enforce it. Stormé had been a chameleon all her life.

That night, she lived up to her name.

Stormé defied police orders, insisting on standing watch over their treatment of her “children” at Stonewall.

Her resistance was met with a club to the face.

In return, the man attached to that club officially met Stormé.

“I walked away with an eye bleeding, but he was laying on the ground, out,” she recounted to PBS.

NYPD couldn’t have known it, but never backing down was Stormé’s specialty.

Born in 1920 as Viva May Thomas, the clear offspring of a Black mother and white father in a time when interracial relationships were still illegal, Stormé had grown up a pariah. She was once so badly bullied, she was left hanging from a fence by her leg, an injury she carried her entire life. The trauma stuck with her too. Even as a queer elder, Stormé wouldn’t repeat the names she’d been called as a child.

“Somebody was always chasing me – until I stopped running,” she said in one documentary.

Finally done running, Stormé started shining.

From a prolific local singing career to a side-saddle horse act with the Ringling Brothers Circus, Stormé confidently found her place center-stage.

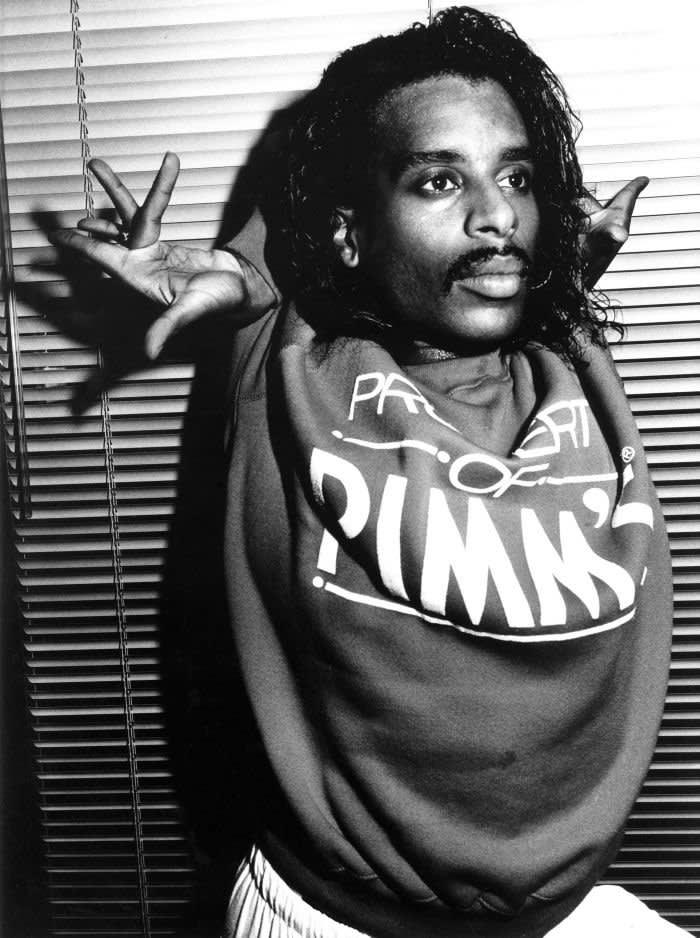

But somewhere along the line—public documentation of Stormé’s life starts to get intermittent as her name changed several times throughout the years—she also discovered that she wanted to shine a little differently.

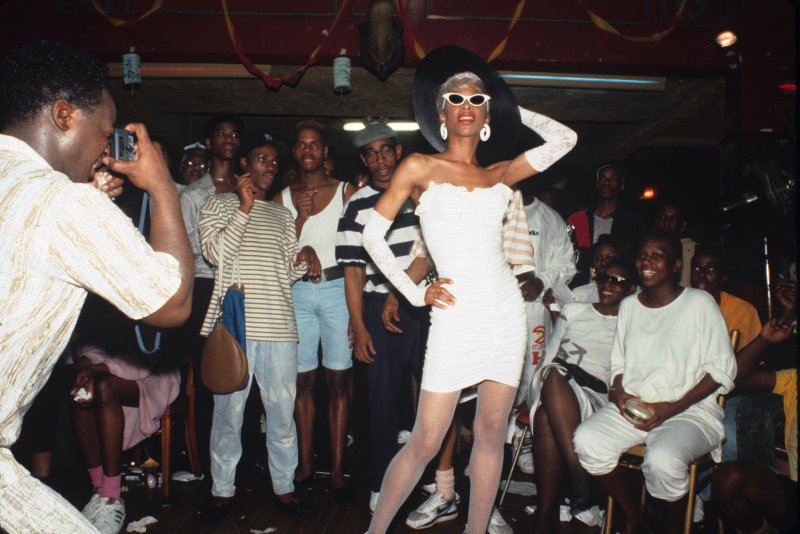

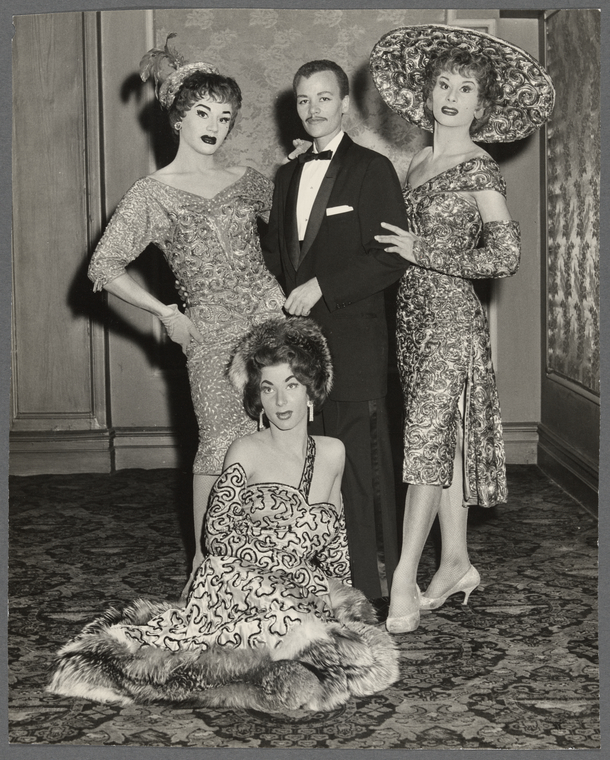

In 1955, Stormé remerged as the only female-born performer at the Jewel Box Revue, a drag burlesque and variety show. At the same time, she unveiled a whole new face.

Stormé remembers that “somebody told me that I would completely ruin my reputation, and…didn’t I have enough problems being Black? I said, I didn’t have any problem with it. Everybody else did.”

Stormé slowly perfected that face until as far as casual observers, paying customers, and consequently, police officers, were concerned, at least on her performance nights, they were looking at a man.

June 27, 1969 was one of those nights.

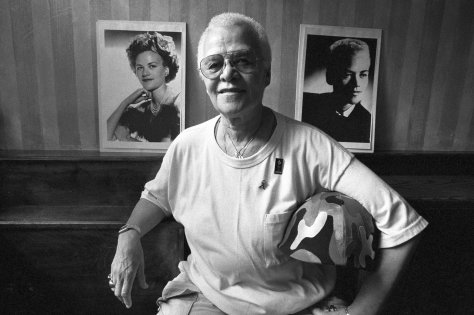

And though Stormé faded from the straight gaze once again, from that night on, she symbolized security in her community in more ways than one.

On July 11, just two weeks after the incident, Stormé became a founding member and Chief of Security of the Stonewall Rebellion Veterans Association.

She worked as a bodyguard, volunteer street patrol, and bouncer for several gay clubs still operating in New York like The Cubby Hole and Henrietta Hudson, but hated those titles.

“I consider myself a well-paid babysitter of my people, all the boys and girls,” a friend recalled her saying.

When AIDS ravaged New York’s gay communities in the 80’s, that same friend asked Stormé for a $5 donation to buy Christmas gifts for those affected.

“Several hours later Stormé walked back into the restaurant with over $2,000,” and subsequently made it her annual tradition, he wrote.

In 1999, Services & Advocacy for LGBTQ+ Elders awarded Stormé their Lifetime achievement award for “crashing the gates of segregation and for the gender-bending example she showed the world,” noting that “she lives her life quietly and does much of what she does very quietly, sometimes anonymously… because what matters to her is that she does what she does, not that it makes a big splash.”

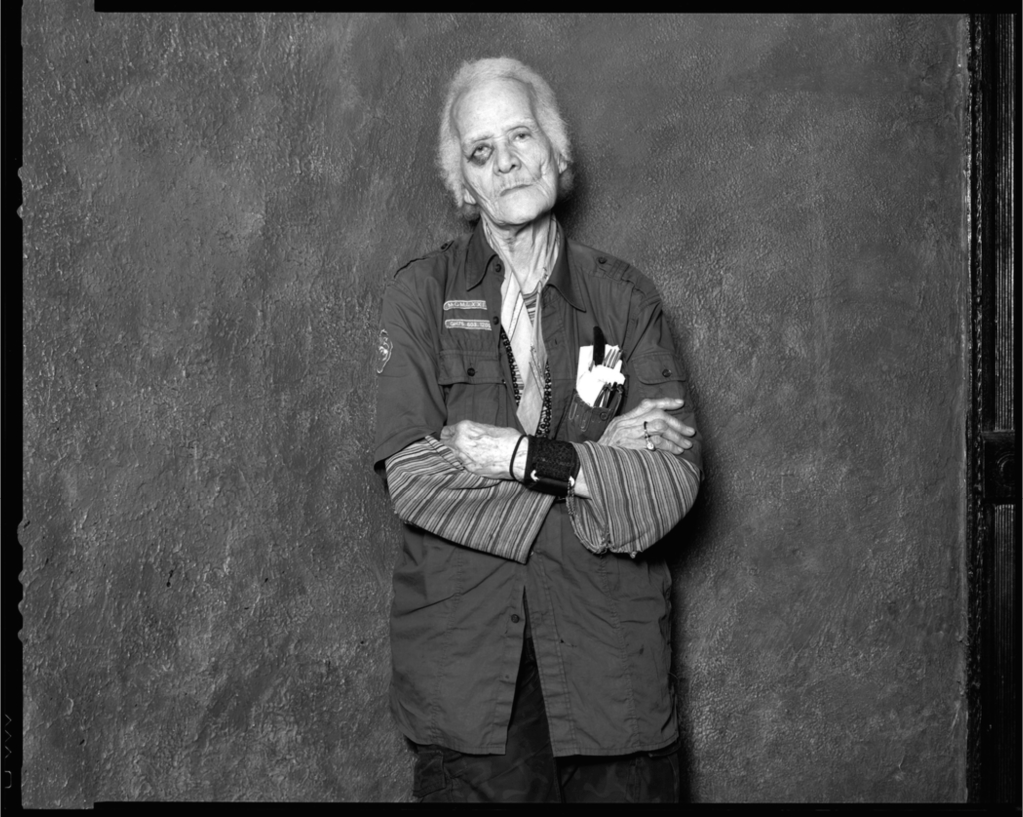

Unfortunately, that quiet life did not serve Stormé well. As she aged and her financial, living, and mental conditions all deteriorated, friends and admirers found themselves rallying others to her aid. Describing her as “someone who gave willingly of herself so that others might live meaningful, fulfilling lives free of discrimination and harassment,” their attempts at supporting an aging Stormé ultimately fell to a non-profit organization.

“I feel like the gay community could have really rallied, but they didn’t,” her friend Lisa told a Times reporter who found Stormé’s absence from NY’s 2010 Pride parade so unusual, he made it his headline.

Four years later, at the ripe old age of 93 (miraculous for anyone, but especially among queer elders), Stormé passed away quietly and alone.

But not forgotten.

When the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor was unveiled inside the Stonewall Inn, 50 names adorned the plaque in honor of the Rebellion’s 50th anniversary.

One of those names was Stormé DeLarverie.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

There’s no more complete history of Stormé’s entire life than the one created by Chris Starfire here.

The Stonewall Veterans’ Association has an extensive entry on Stormé’s activism here.

The Code Switch podcast tackles Stormé’s story through an intersectional lens of queer pride, police brutality and racism, all topics prevalent throughout her life and still relevant today. Listen in here.

Read Stormé’s obituary published in the New York Times on May 30, 2014.