There’s a not-so-secret slander running through the undercurrent of American history & media. It’s fairly obvious if you know what to look for… or if you’re a Black American.

For example, Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?” is one of the earliest pieces of African-American literature introduced in elementary & middle-school curriculums. Most famously appearing in an April 1863 issue of the New York Independent, transcribed by Ms. Frances Gage (an associate of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton) twelve years after the speech was delivered, “Ain’t I A Woman” is written in thick southern colloquialisms and the supposed vernacular of an enslaved person,

But journalist Marius Robinson published the same speech on June 21, 1851 in The Anti-Slavery Bugle, and not only is it written in clearly decipherable King’s English, the words “ain’t I a woman?” NEVER appear in that version, approved for print by Sojourner Truth herself.

Not convinced? Think she pulled a favor from a friend? Think again. Sojourner Truth’s first language wasn’t English or an African language, but Dutch. She was born in Swartekill, NY. The only evidence that Sojourner would have spoken as presented in “Ain’t I A Woman?” is Frances’ Gage’s account itself, appearing second in historical records and over a decade later.

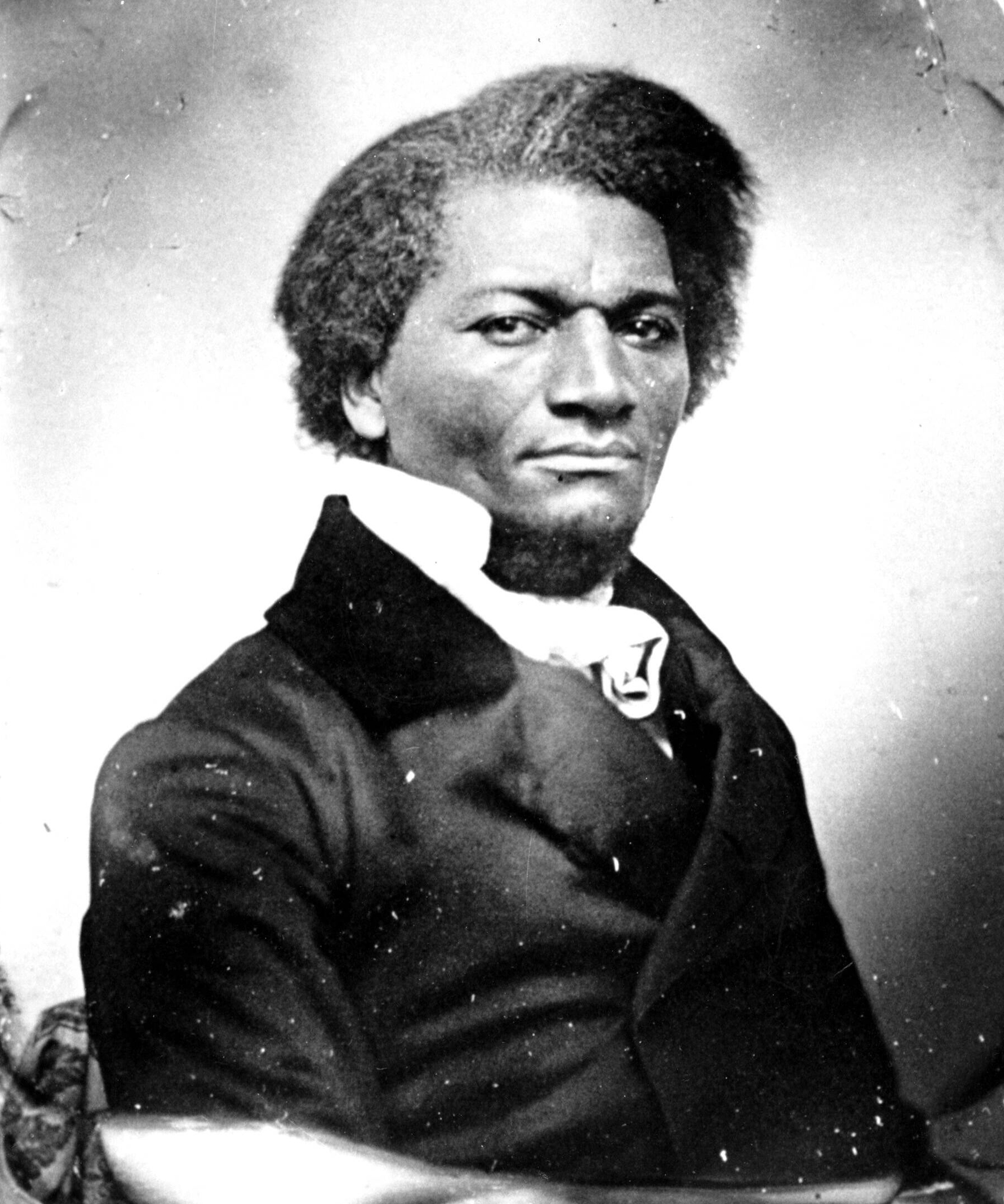

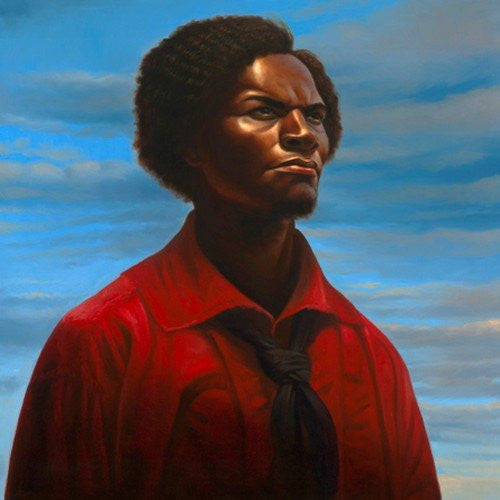

For a more visual representation, consider another of the few African-American figures who frequents American history books: Frederick Douglass. There are 160 known photographs of Frederick Douglass, more even than President Abraham Lincoln. And yet, the image of Mr. Douglass we know best is most likely that of a stern-faced, graying, relatively unapproachable man. No one ever sees the young Frederick Douglass, proud, handsome, full of personality.

RIGHT: the Frederick Douglass we COULD know.

Frederick Douglass was the most photographed person in his lifetime, and though he rarely smiled because he didn’t want to be seen or represented as a “happy slave,” why do we only see the harshest version of him when so many exist?

Even today, media representations of African-Americans tend toward extremes. Criminals or memes. Rappers or impoverished. Jezebel, Mammy. Sapphire.

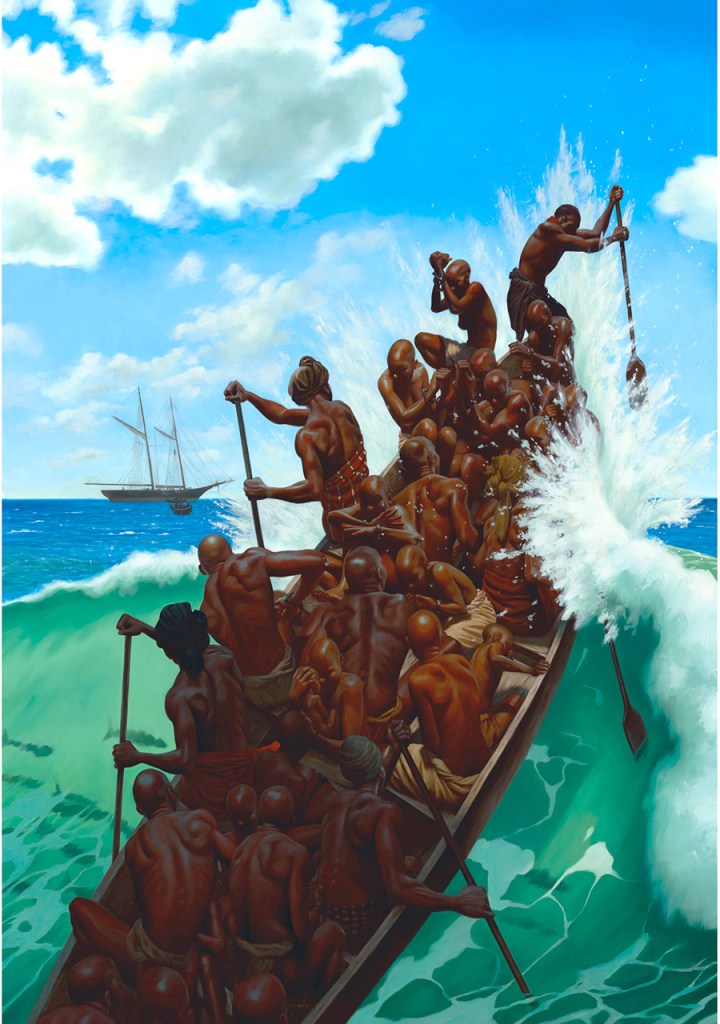

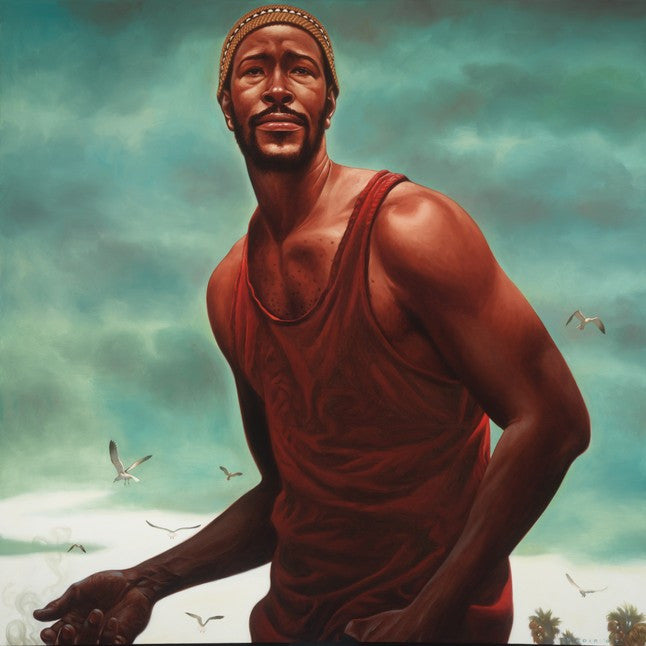

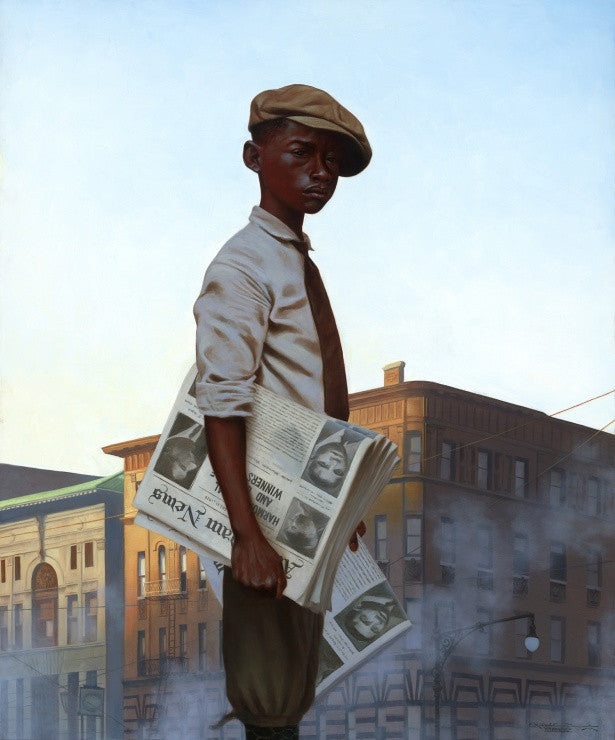

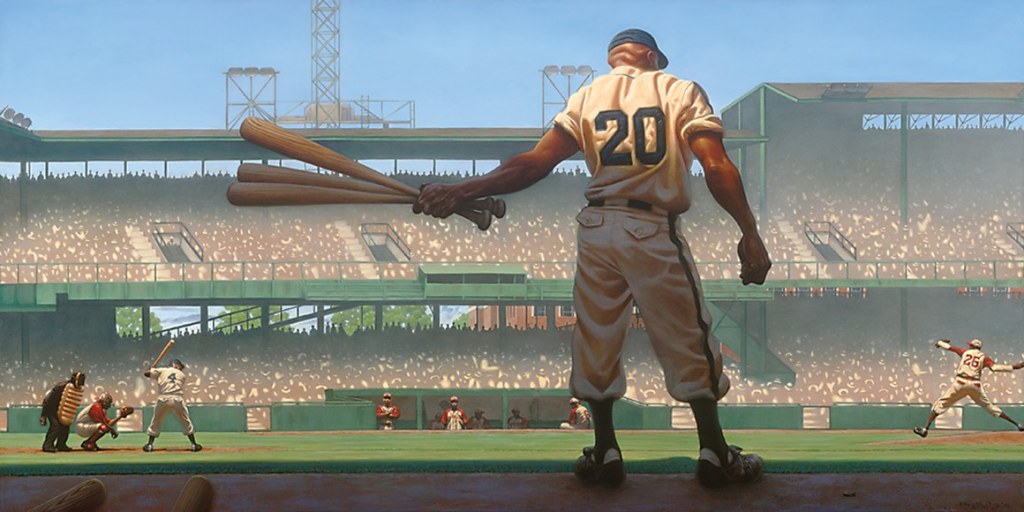

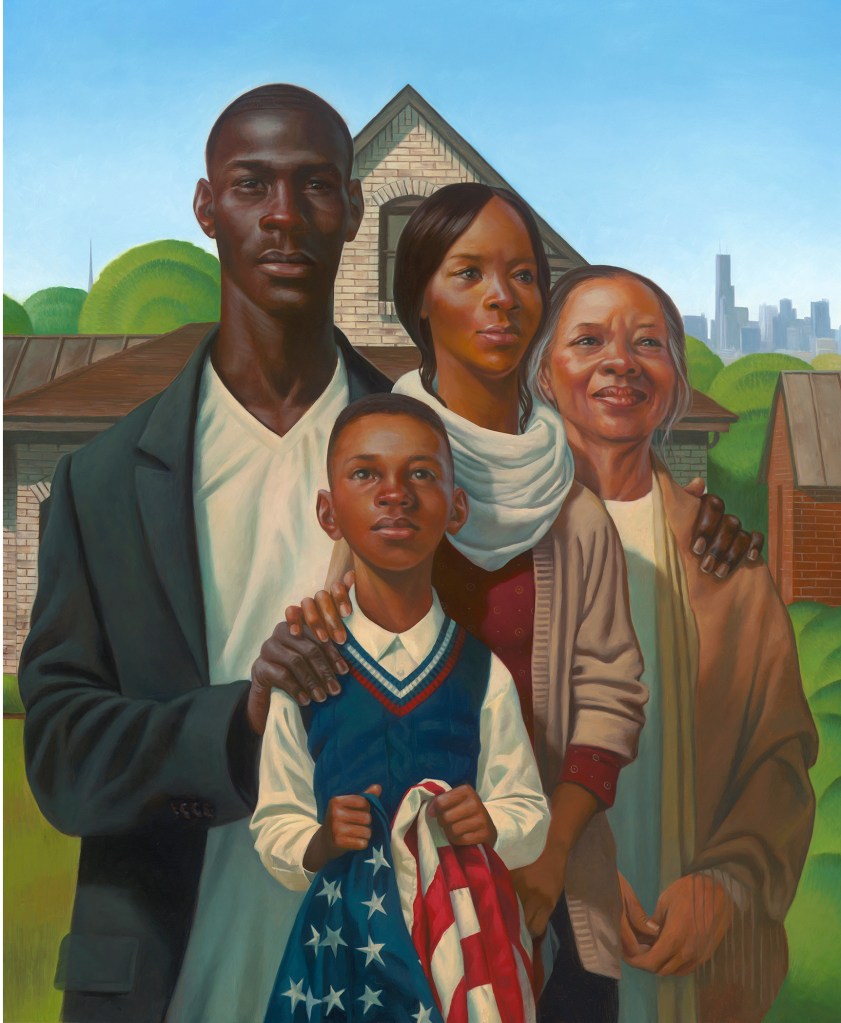

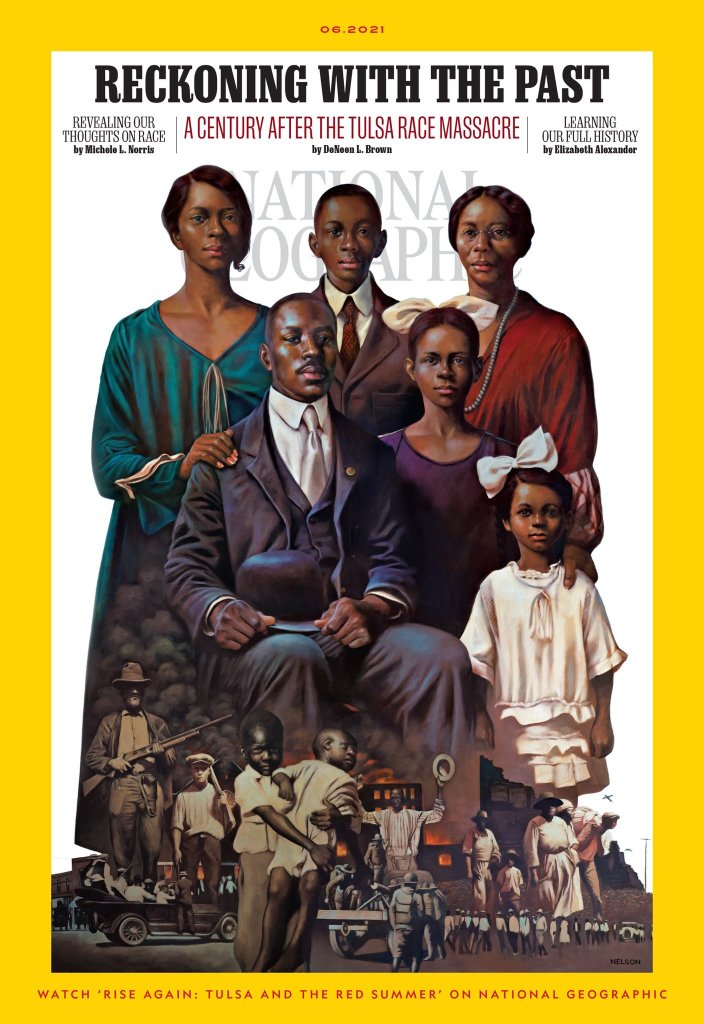

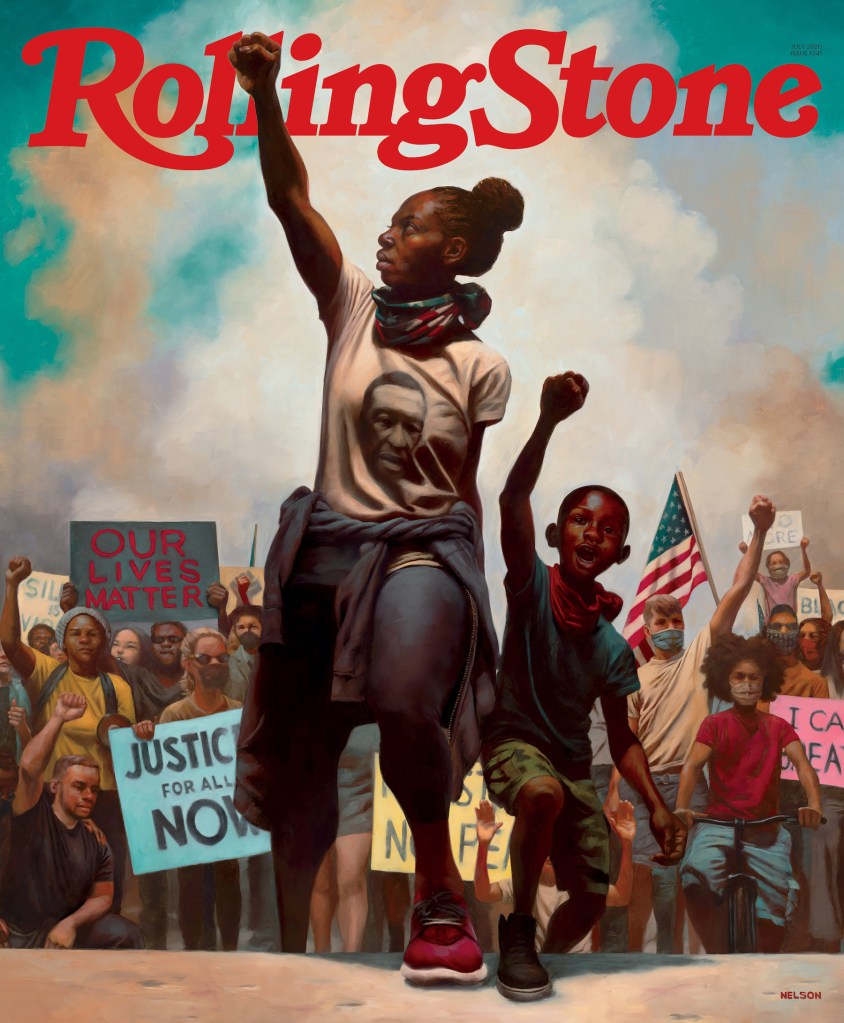

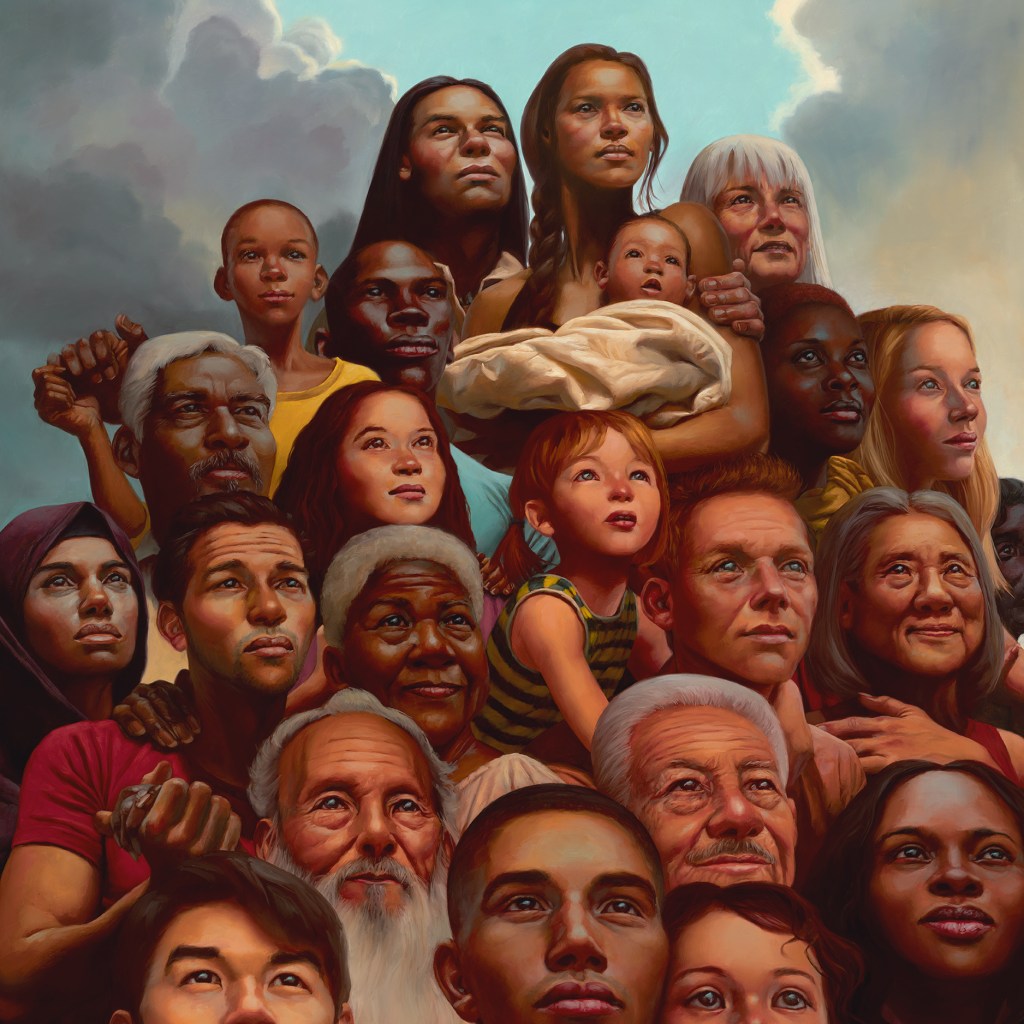

In this historical context, Kadir Nelson is more than an illustrator. He’s the hand holding a mirror to the truth.

Through Kadir’s paintings and illustrations, we see Black people from all over the world represented through eyes that adore them, not by those who would use them for their own gains, those who would undermine their credibility, or those who’d keep them out of positions of power.

But Kadir’s artistic vision wasn’t always so clear. As a child, his mother, who didn’t pursue her own passions for art, highly encouraged his. Nevertheless, he attended the illustrious Pratt Institute as an architecture major for the age-old reason: money. Despite the idealized “starving artist” archetype, the “unemployed, impoverished and Black” stereotype deters so many African-American creatives from pursuing their true calling. Luckily, only a year in, Kadir couldn’t resist his, changing his major to illustration instead.

“I have taken on the responsibility of creating artwork that speaks to the strength and inner beauty and outer beauty of people from all over the world,” Kadir said. “I like to create paintings of people who have overcome adversity but by being excellent or being strong or intelligent or having big hearts to remind people that they share those same qualities. When they see the paintings and feel the spirit of the people I am depicting, they are reminded of that within themselves. It all speaks to the story of the triumph and the hero that lives in all of us. If people take anything away from my work, that’s what I hope they take away from it.”

They most certainly did. Kadir’s first job was as a concept artist for the critically acclaimed film, Amistad. Since then, his work has lived in The National Baseball Hall of Fame, the US House of Representatives, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and many, many more.

But Kadir’s work isn’t out to glorify the myth of Black exceptionalism. He recalls a moment of everyday Blackness as inspiration he holds onto still. “My family was piling into my grandmother’s white Cadillac and I stood and waited for everyone to get inside. It was cold and breezy, and warm streetlights reflected off the shiny bluish sidewalk. I stood there feeling warm, wrapped up in my heavy winter coat, enjoying the breeze and the scenery. I remember thinking to myself, ‘This is beautiful.’ I was a six-year-old kid savoring the moment. It felt pretty special to me.”

Life’s littlest moments always are the most special, and those moments are so rarely seen occupied by Black faces. While validation from the mainstream was never necessary, the wider world has definitely taken notice of Kadir’s celebration of authentic Blackness as well. His art has been commissioned by HBO, Nike, Coca-Cola, National Geographic, Rolling Stone, and the list goes on and on.

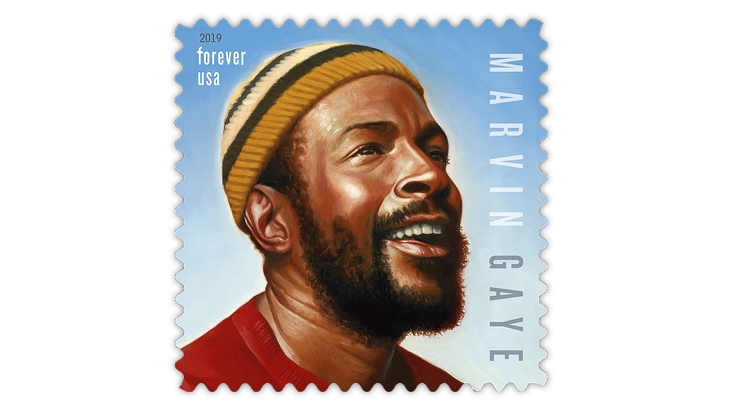

The illustration work that he’s personally published or collaborated on outnumbers everything I’ve mentioned so far. His book illustrations have won too many awards to count from names like Caldecott, Scholastic, New York Times, and more authorities in the field. Kadir’s paintings also hang for purchase in high-end galleries, grace an assortment of music album covers, and have even appeared on USPS stamps. He might well be one of the most saturated African-American visual artists of the 21st Century, if not all the centuries. Perhaps because the truth resonates.

“I feel that art’s highest function is that of a mirror, reflecting the innermost beauty and divinity of the human spirit; and is most effective when it calls the viewer to remember one’s highest self… as it relates to the personal and collective stories of people,” he says.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, Kadir’s speak volumes upon volumes.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Browse Kadir’s portfolio of illustrations and commissions, and shop his gorgeous prints at his website.

Keep Kadir’s beautiful representations of Blackness and other Americana close at hand with a follow on Instagram.