“Slavery” is a cold, factual word that tidily boxes up millions of personal indignities repeated over and over again.

“Freedom” is usually considered its opposite, but I’d propose another: “agency.”

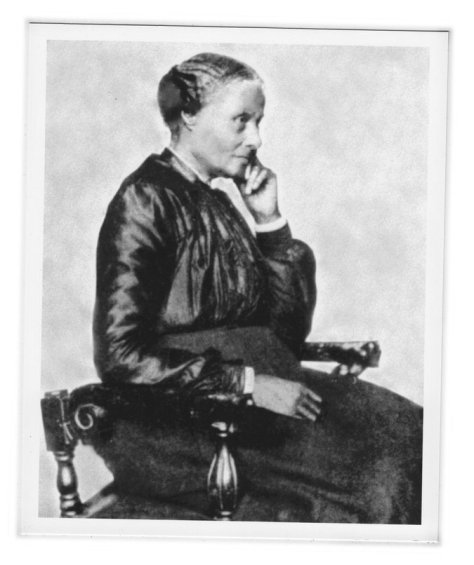

Everything about the antebellum Virginia world Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly was born into was designed to deprive her of agency. She lived to take it back.

Elizabeth’s mother Aggy wasn’t as fortunate. Her daughter’s father wasn’t her husband George, but her owner Armistead Burwell. She’d attempted to claim what little agency she could in the circumstances by rejecting her enslaver/rapist’s last name in favor of her husband’s: Hobbs. Aggy didn’t share that truth with her daughter until her deathbed. Perhaps it brought back too many bad memories, like how Burwell gave the Hobbs family two hours notice before selling George to a slaver in the West. Elizabeth recalled their collective helplessness in her autobiography: “I can remember the scene as if it were but yesterday;–how my father cried out against the cruel separation; his last kiss; his wild straining of my mother to his bosom; the solemn prayer to Heaven; the tears and sobs–the fearful anguish of broken hearts… the last good-by; and he, my father, was gone, gone forever.”

Prized by the Burwells for her many talents, especially the seamstress skills that she was expected to teach her daughter, Aggy was kept. But Aggy could also read and write, and likely taught her daughter those skills as well. Instead of the domestication expected of her, Elizabeth eventually wielded her needle and pen as silent weapons of subversion instead.

That subversive streak simmered early on. As a teenager, she was sent to North Carolina to work in the service of her (then unknown) half-brother Robert. Perhaps because Robert’s wife Margaret easily guessed the source of Elizabeth’s light skin and wanted to punish her for it, or perhaps simply because she was cruel, Margaret enlisted the help of a neighbor to “break” Elizabeth. When the neighbor summoned Elizabeth, demanding that she strip down for her first humiliating beating, she replied, “You shall not whip me unless you prove the stronger. Nobody has a right to whip me but my own master, and nobody shall do so if I can prevent it.” She could not. Week after week, Elizabeth was beaten until her abuser was too exhausted to continue. Week after week, “I did not scream; I was too proud to let my tormentor know what I was suffering,” she wrote. Eventually, it was he who “burst into tears, and declared that it would be a sin” to continue inflicting such harm upon an innocent human being.

But her torment did not end, and a new owner inflicted a different physical punishment on Elizabeth. “For four years, a white man—I will spare the world his name—had base designs upon me. I do not care to dwell upon the subject, for it is one that is fraught with pain. Suffice it to say that he persecuted me for four years, and I… I became a mother,” she wrote.

Then and now, there is no greater personal indignity, but Elizabeth’s despair over that act went deeper: “I could not bear the thought of bringing children into slavery — of adding one single recruit to the millions bound in hopeless servitude.”

When Armistead Burwell died, Elizabeth returned to Virginia to care for his heirs, then accompanied them to St. Louis. That’s where she began stitching her terrible circumstances into gold.

By then, the family had grown to 17 members, and without a patriarch and his estate, they were destitute. Elizabeth was the only one among them with employable skills, and she was hired out to sew for other families, eventually growing that casual business arrangement into an actual business that single-handedly supported all 17 people.

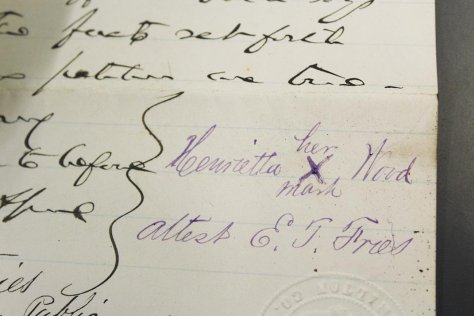

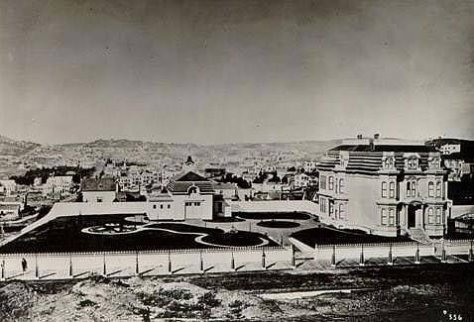

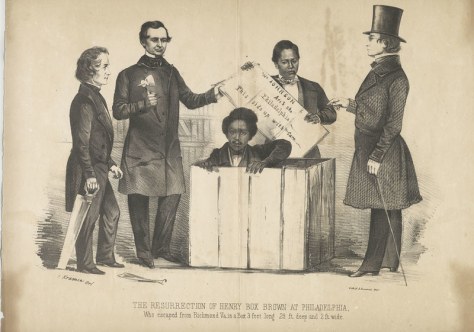

Seeing her true value, Elizabeth made an offer to her owner. She would buy her freedom and her son’s for $1200. At first, he refused. Then he tried to trick her, saying he would accept no payment, but offering to pay her passage on the ferry across the Mississippi. She was smart enough to know that the Fugitive Slave Act meant she could be returned to her owner anytime, and she refused. In 1855, she finally gained her independence and made her first fateful decision. Elizabeth took her talents to the nation’s capital, where they caught the eye of a very important lady: Mary Todd Lincoln.

Under the First Lady’s employ, Elizabeth flourished. In a single season she fashioned almost 20 dresses, many of which were complimented by the President himself. In Mrs. Lincoln, Elizabeth also found a timely friend. Elizabeth and Mary both lost sons in 1861 and 1862, respectively. That experience reshaped their very personal business relationship into a friendship. “Lizabeth, you are my best and kindest friend, and I love you,” Mrs. Lincoln once wrote. Best of all, she put her money where her mouth was.

Elizabeth was in high demand among D.C.’s high society women, even the wives of Confederacy President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee. And in true subversive fashion, she used their old southern money to employ more Black women in her shop and create the Contraband Relief Association, an organization that provided support, relief and assistance to formerly enslaved people.

Mrs. Lincoln regularly donated to the Contraband Relief Association, and requested that her husband do the same. “Elizabeth Keckley, who is with me and is working for the Contraband Association, at Wash[ington]–is authorized…to collect anything for them here that she can….Out of the $1000 fund deposited with you by Gen Corcoran, I have given her the privilege of investing $200 her.. Please send check for $200…she will bring you on the bill,” she wrote to President Lincoln.

But alas, everyone reading knows what came soon enough. President Lincoln was assassinated, and with his death, public opinion of Mary and the ladies’ friendship unraveled. Elizabeth published her autobiography, believing it would salvage both and bolster her income, but her good intentions backfired.

“Readers in her day, white readers — they took it as an audacious tell-all,” Jennifer Fleischner, author of “Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly” said. “You know, ‘How dare she’? There were two categories: the faithful Negro servant or the angry Negro servant. Keckly was neither servant, nor faithful, nor angry. She presented herself, the White House and Mary Lincoln as she saw and knew them. And that didn’t work.”

Mary was devastated by the personal revelations Elizabeth included, society women found it distasteful and didn’t want to appear in the pages of a book themselves, politicians spun it as reasons African-Americans shouldn’t be able to read, write or integrate with regular society, and that was that for Elizabeth. She died in her sleep in 1907, at a home for poor women & children that the Contraband Relief Association had founded.

But her story didn’t end there. Though it was suppressed upon its initial publication, Elizabeth’s biography is in print once again, and considered one of the most substantial documentations of the Lincoln White House surviving today, and proof of the value in owning your own story.

*Ed. Note: I’ve spelled Elizabeth’s last name as “Keckly” because that’s how she spelled it. She was historically recorded as “Keckley” and that spelling has persisted.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

The Smithsonian National Museum of American History details how Elizabeth put her money to work for the people.

The New York Times featured Elizabeth’s biography in their “Overlooked” series that runs modern-day obituaries of famous contributors to American history that their paper overlooked at the time.

The White House Historical Association has thoroughly documented Elizabeth’s life from her autobiography and their own records as part of their “Slavery in the President’s Neighborhood” initiative.