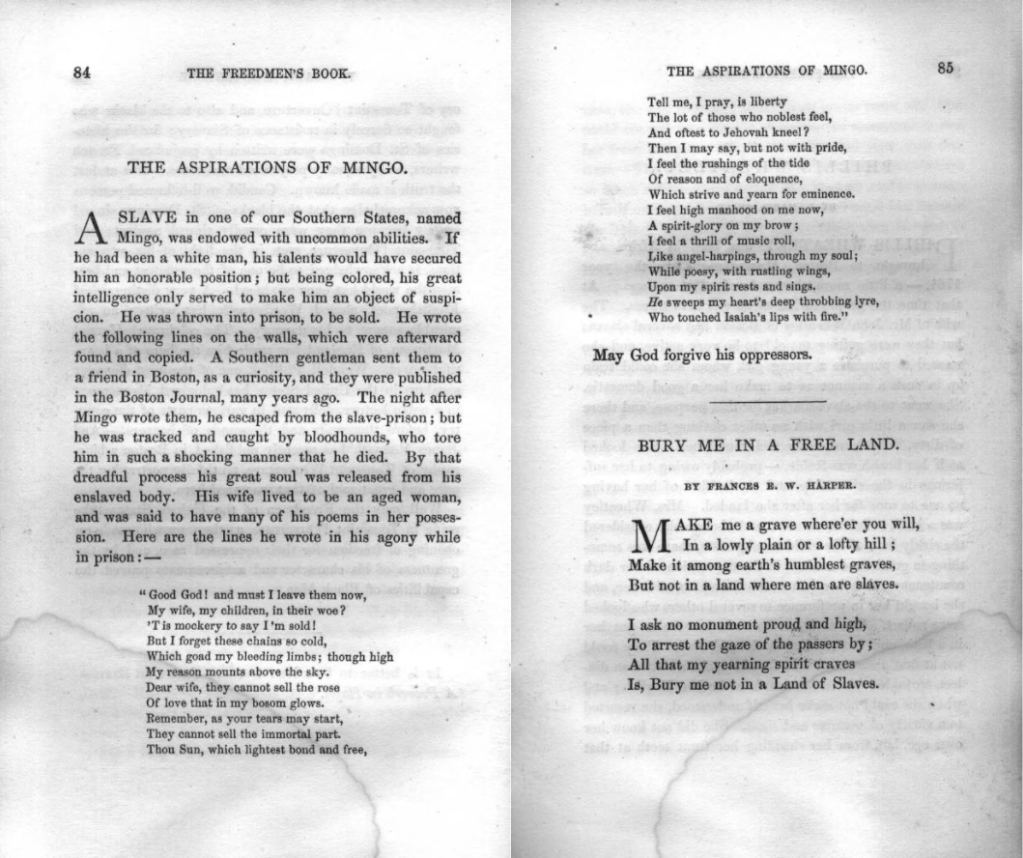

“If he had been a white man, his talents would have secured him an honorable position; but being colored, his great intelligence only served to make him an object of suspicion.”

Those words, written by L. Maria Child, editor of The Freedmen’s Book and an active abolitionist, preface a poem inscribed on a prison wall by an enslaved man named Mingo before he was torn apart by pursuit dogs.

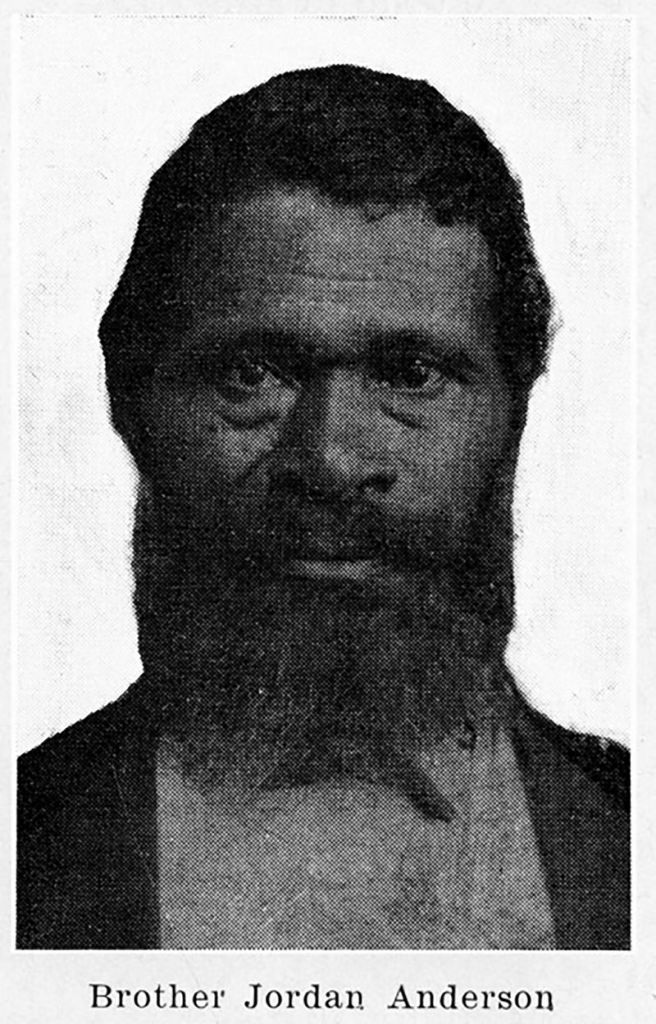

Over 150 years after the Freedmen’s Book went into print, those words still rang true. This time, regarding another writer in the compilation: Jourdon Anderson.

Over the past decade, Jourdon has occasionally gone viral for his response to an 1865 letter from his former owner. Jourdon’s flawless delivery, scathing wit, and audacious request for back pay left “some critics question[ing] the letter’s authenticity,” as Smithsonian Magazine very politely puts it.

But it’s also very telling that several outlets that picked up the story compared Jourdon’s writing to another, more famous writer’s style. Mark Twain’s first book was published in 1869, just four years after Jourdon’s letter. If Mark Twain could write so cleverly and with such tremendous style, why couldn’t Jourdon Anderson write like this?:

To my old Master, Colonel P. H. Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee.

Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again, and see Miss Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.

I want to know particularly what the good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,—the folks call her Mrs. Anderson,—and the children—Milly, Jane, and Grundy—go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated. Sometimes we overhear others saying, “Them colored people were slaves” down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they hear such remarks; but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to Colonel Anderson. Many darkeys would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you master. Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars. Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq., Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense. Here I draw my wages every Saturday night; but in Tennessee there was never any pay-day for the negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter, please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up, and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve—and die, if it come to that—than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters. You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood. The great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

From your old servant,

Jourdon Anderson.

So why would anyone doubt Jourdon? Because Jourdon was enslaved.

Even before Sojourner Truth’s words were twisted into a mockery, the editor of the Freedmen’s Book knew to defend against the same thing happening to the words within its pages.

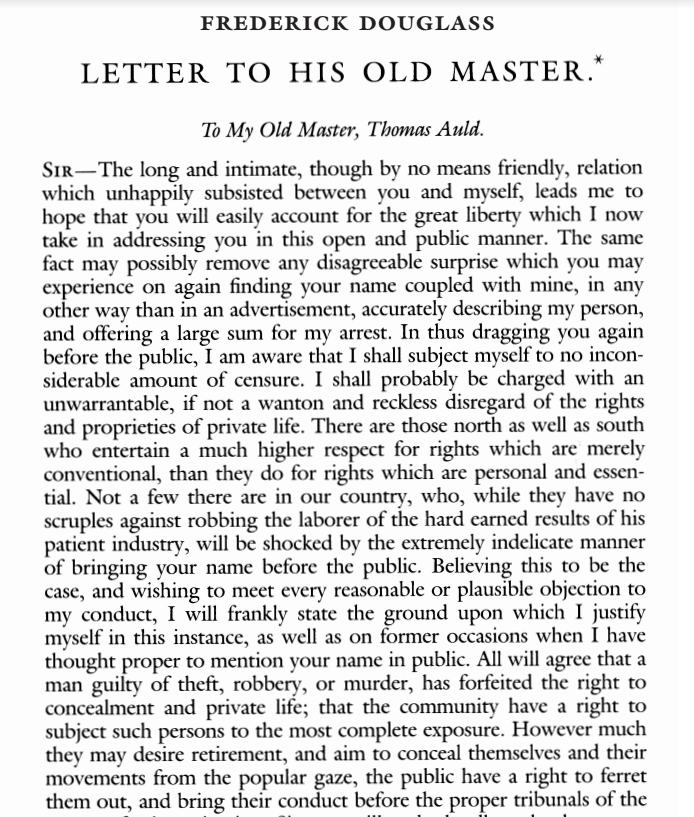

of you as a means of exposing the character of the American church

and clergy-and as a means of bringing this guilty nation, with

yourself, to repentance,” and closing with “I am your fellow-man, but not your slave.” Read it in full here.

And again, why?

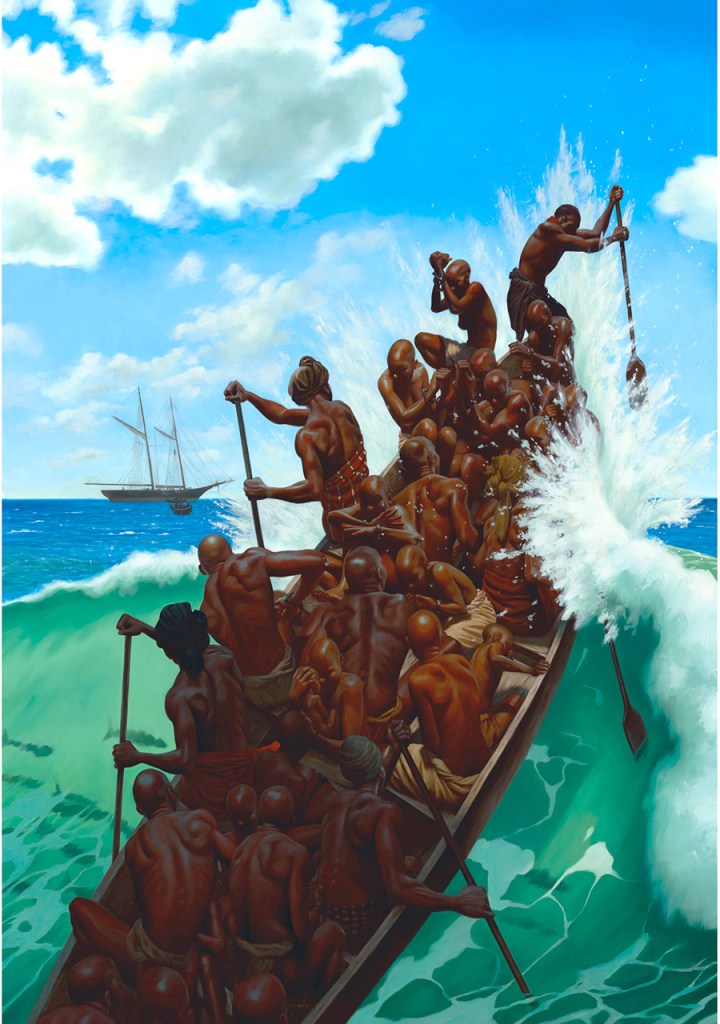

Because the Trans-Atlantic slave trade couldn’t have survived 400 years if the people enslaved were seen as intelligent, thoughtful, sympathetic and autonomous human beings.

That’s why.

I freely admit bias, so I’ll share independent words from Roy E. Finkenbine, a professor at the University of Detroit-Mercy: “It’s kind of a racist assumption… that when someone is illiterate, we make the assumption they’re stupid. Enslaved people had deep folk wisdom and a rich oral culture,” he adds. “Why would we think that he hadn’t been thinking about these things and couldn’t dictate them to willing abolitionists?”

The opening quote of this post is just one clear attribution prefacing several inclusions in the Freedmen’s Book, and Jourdon’s letter has one as well: “[Written just as he dictated it.]”

But we don’t have to take the word of the Freedmen’s Book. Historic record backs it up.

Jourdon’s letter is dated August 8, 1865. An issue of The New York Tribune dated August 22, 1865, just two weeks later, ran the same letter (from a Cincinnati paper), with a different certification: “The following is a genuine document. It was dictated by the old servant, and contains his ideas and forms of expression.”

So now that we’ve established a timeline of independent sources, here’s the twist that’s not as frequently reported in this viral tale: Just a month after Jourdon’s letter was written, Col. Anderson was forced to sell his plantation in payment for his debts. The Thirteenth Amendment officially abolishing slavery was ratified by all of the states in December of the same year. Begging Jourdon to come back was quite literally Anderson grasping at straws.

According to Raymond Winbush, director of the Institute for Urban Research at Maryland’s Morgan State University who tracked down some of Col. Anderson’s descendants, to this day, the family is “still angry at Jordan for not coming back, knowing that the plantation was in serious disrepair after the war.” As he’d spent 32 years enslaved by the Andersons, Jourdon was intimately familiar with their plantation, and they’d hoped that if he returned, others they’d enslaved might stay on, even after they’d been freed. Instead, Col. Anderson died destitute in 1867, only two years after his missive to Jourdon.

As for Jourdon, he lived another 40 years in Dayton, OH, passing away at 79 in 1905. His obituary is even referenced in the archives of the Dayton Daily News, and he’s buried next to his Mrs. in Dayton’s Woodland Cemetery and Arboretum.

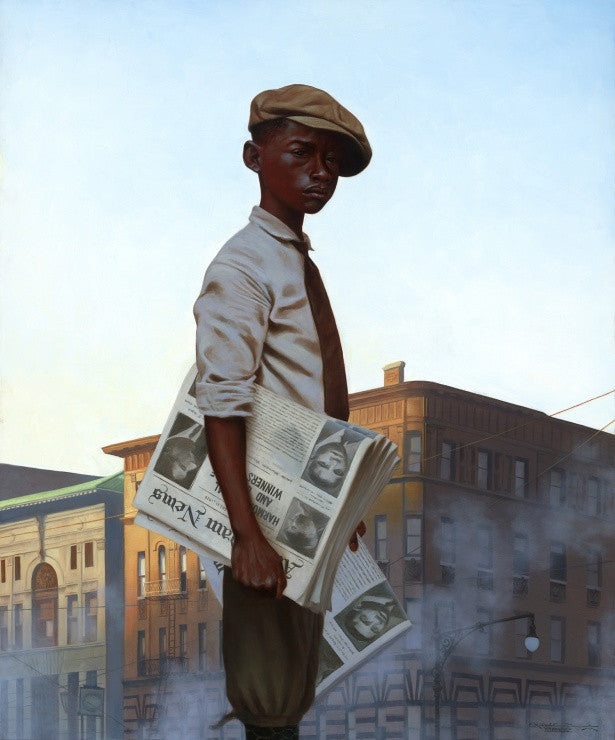

Jourdon’s family and many more prospered too. Among many other achievements in Dayton, Jourdan’s son, Dr. Valentine Winters Anderson, was a supporter of renowned poet Paul Laurence Dunbar in establishing the Dayton Tattler, the city’s first Black newspaper.

Times may change, but Jourdon and his family are shining examples that the power of the written word lives forever… as long as the rewriters of history will let it.

*Ed. Note: As usual, I’ve spelled Jourdon throughout the same way it was spelled in his original letter, not as history recorded him.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Read Jourdon’s letter as it was published in the Freedmen’s Book at the Dickenson College Archives.

More records authenticating Jourdon’s life and ancestors, along with those of his enslaver’s, is available with context from current historians, through an article circulated by the Associated Press.