Each winter, from a window high above New York’s Central Park, Mabel Fairbanks gazed down in awe at each of the tiny figures dancing over the frozen pond. One winter, she decided to stop being an onlooker, and with a couple of dollars she’d scraped together from babysitting earnings, Mabel marched down to a nearby pawn shop, and bought herself some brand new used ice skates. Even two sizes too big and stuffed with cotton, they were her first major step toward making it on the rink.

In the late 1920s, she was only fourteen and still too young to know that no matter how much skill she demonstrated on those blades, she’d be iced out of figure skating. Born Black and Seminole, someone like Mabel was a literal blemish against the lily white landscape of the sport.

In fact, Mabel’s first experience on the ice was in Harlem. Even though the ice was better in Central Park, she didn’t have the confidence to skate back where she’d first seen it happen, back where people didn’t look like her. But with a little encouragement, she went for it, and her bravery was rewarded. “I got on the pond and then I discovered that I could skate around too, just like the other kids,” she said. “Blacks didn’t skate there. But it was a public place, so I just carried on.”

Naturally, she stood out among the crowd.

And for once, the color of her skin wasn’t the only reason.

Spectators took notice of Mabel’s talent and one suggested that skills like hers belonged on a real rink. But when she followed that suggestion, Mabel discovered that talent doesn’t matter when you can’t even get through the front door.

“I stood in line and said, ‘I’m next, I’m next!’ but I’d get up front and they would just push me away,” she recalled.

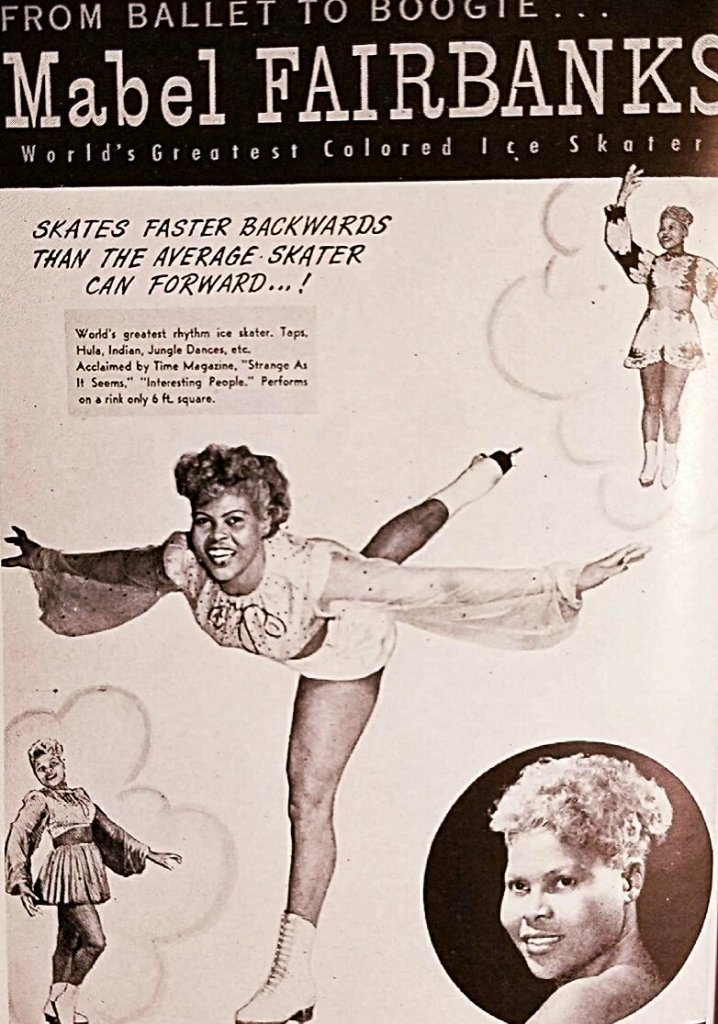

She wasn’t giving up that easily. If Mabel couldn’t get into a rink, she’d bring the rink to her. With the help of a relative, she built her own 6×6 indoor practice rink: a block of wood and dry ice, topped with sheet metal and freezing water.

Mabel’s persistence paid off when she was finally admitted into that real indoor rink (even if it was after hours). She was noticed again, and this time, it was by figure skating royalty. Olympian and nine-time U.S. ladies champion Maribel Vinson Owen helped Mabel perfect her technique and encouraged her to keep going, even if she had to go it on her own.

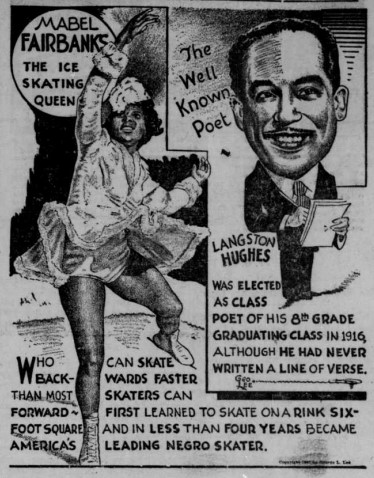

So Mabel packed up her tiny personal rink and did just that. She took skating places it had never been before like the Renaissance Ballroom, the Apollo Theater, and social clubs all over New York City and Harlem. Each show was more than a novelty; Mabel was skilled enough to perform some of figure skating’s most difficult routines, and create her own moves too. The New York Age, one of America’s most prominent historically Black news publications, credited Mabel as the inventor of the Flying Waltz Jump, the Camel Parade, and the Elevator spin, even though they weren’t named after her as per the standard in figure skating.

By the 1930’s, Little Mabel from Central Park had grown into a sensation.

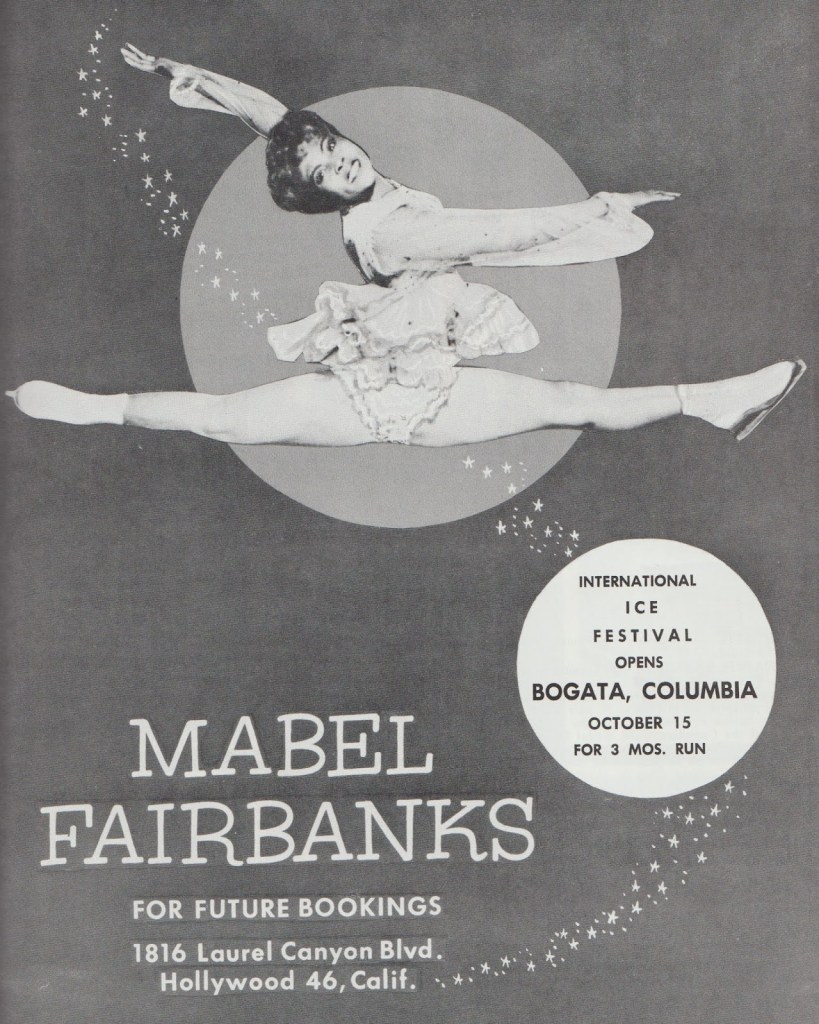

But she still couldn’t try out for the Olympics, because she couldn’t gain admission to a qualifying event. So once again, Mabel made her own way.

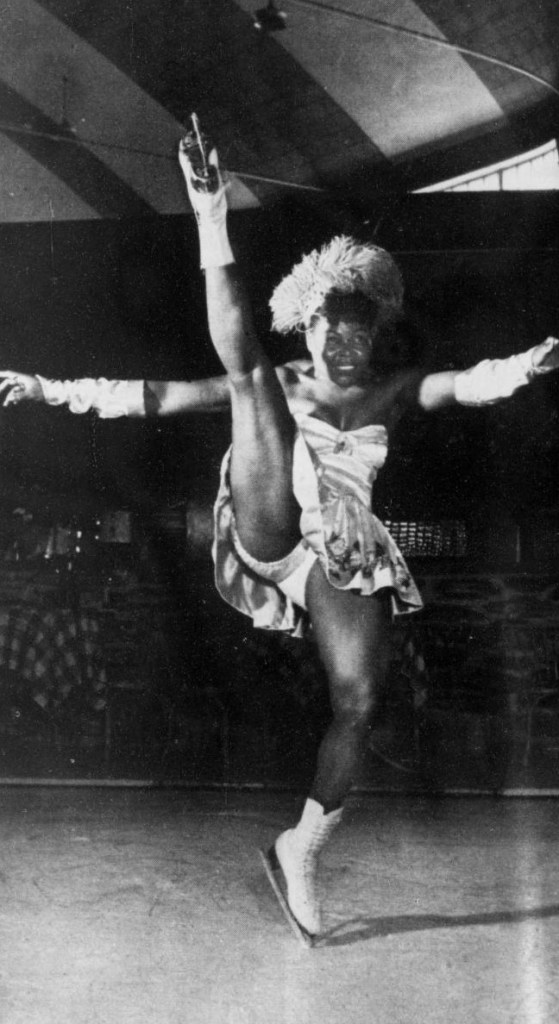

Mabel skated her way through interracial ice tours and USO clubs in France, Germany, Cuba, Japan, and all over the world before coming back to the States as a bonafide star. Her show included flying splits and other death-defying jumps, wildly flexible grabs, and unbelievable balance through it all. When she took that show to Vegas, celebrities and Hollywood flocked to witness Mabel’s talent unlike they had ever seen before, and certainly unlike they’d been allowed to see before from a Black woman.

But she STILL had to run a whole campaign to be able to practice at the Pasadena Winter Gardens, where she and her skates were greeted by a sign reading “Colored Trade Not Solicited” (read: “Melanated people, go elsewhere.”) And even when she toured with the Ice Capades, she was expected to eat separately from the rest of the cast.

And still, her star power couldn’t be denied. By 1951, Mabel landed a regular role on an LA television show called “Frosty Frolics,” where she could dazzle viewers watching at home. For the next four years, Mabel appeared on television and toured in ice skating shows, until “Frosty Frolics” was finally canceled and she found a new calling. Words from her very first mentor, Maribel Vinson, still echoed in Mabel’s mind: “‘Mabel, there are never going to be Black kids in competitions or even ice shows unless you do something about it.’”

When the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964, Mabel had a stable of Black skaters ready to break into the sport. It was only 2 years before one of her students, Atoy Wilson, became the first African-American figure skating champion. Since then, many more skaters of color like Debi Thomas, Kristi Yamaguchi, and Tai Babilonia have come under her wing and gone on to be champions. She even gave a young Scott Hamilton skating lessons as part of a program she established for skaters whose families couldn’t afford the monumental costs of elite figure skating, as she campaigned for greater accessibility all around in the sport.

Constantly pushing boundaries, Mabel continued coaching, mentoring and financially assisting skaters until she was 79 years old. Though she was never able to skate competitively herself, Mabel’s tireless contributions to the sport did not go unrecognized, and she was inducted into the United States Figure Skating Hall of Fame in 1997, the first African-American to be so acknowledged.

Before her death in 2001, Mabel told the Los Angeles Times, “If I had gone to the Olympics and become a star, I would not be who I am today.”

And who she was changed the face of figure skating forever.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Teen Vogue compares and contrasts Mabel’s story with the picture of figure skating today.

The LA84 Foundation, created by the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee has preserved and transcribed Mabel’s whole life story in her own words here.

Read about and donate to the U.S. Figure Skating Association’s “Mabel Fairbanks Skatingly Yours” Fund to “financially assists and supports the training and development of promising figure skaters who are Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) with the goal of helping them realize and achieve their maximum athletic potential.”

Keep exploring Mabel’s life through Mental Floss’s extremely well-documented article with links to more historical sources to dive into.

Hear from more underrepresented voices carrying Mabel’s torch into figure skating today and the barriers they still face via NBC News.