“We had to practice nonviolence because if we didn’t, we’d get the sh*t kicked out of us.”

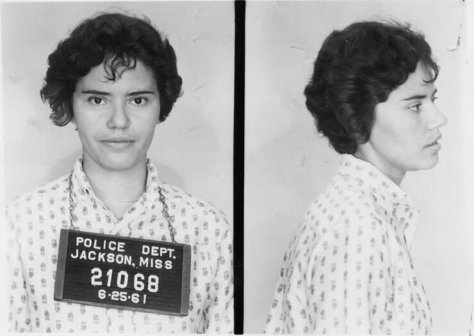

Mary Hamilton was non-violent all right. But the lady had a tongue sharp enough to commit murder, and when the state of Alabama refused to put some respect on her name, she showed them just how deeply she could cut. Like most of the Freedom Riders, Mary was no stranger to gross insults, physical and mental humiliation, petty imprisonments, and violent beatings. Unlike many of her companions, turning the other cheek didn’t come so easily, so if she couldn’t fight back with her hands, Mary wielded words as her weapon of choice. As her daughter later told NPR, “Dr. King called my mother Red, and not for her hair but for her temper. For a nonviolent movement… she was one to get pissed off.” Jailers, doctors, not even the mayor of Lebanon, Tennessee escaped the righteous indignation spoken from the mouth of this black woman.

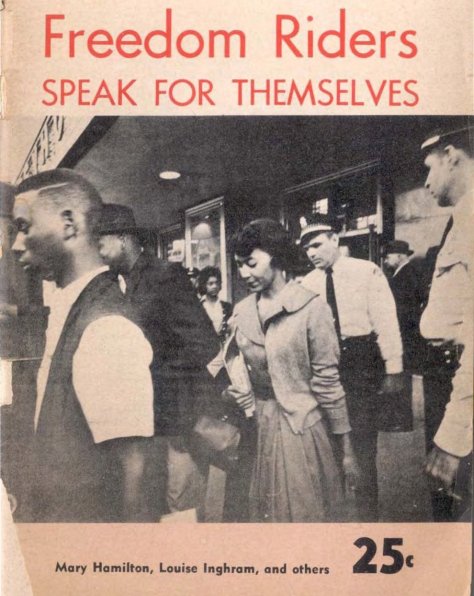

Men with that level of status were especially not accustomed to such treatment from a woman who could pass for white but self-identified as black, even in the worst of circumstances. In a book of letters from Freedom Riders, she recalled, “The official who checked our money and belongings had put on my slip I was white. When the girl behind me told me, I notified him otherwise. He was very angry. He told me that I was lying. He then took it upon himself to decide what other races I could be, and told the typist to put down that I am Negro, white, Mexican, and I believe that’s all. This made me very angry.”

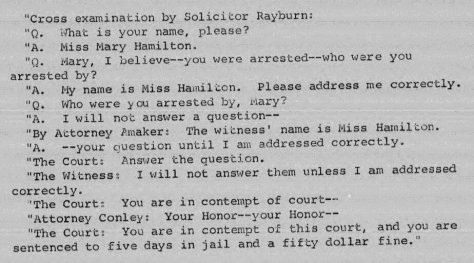

Identity was everything for Mary DeCarlo who was so committed to living her truth that she dropped her father’s Italian surname in favor of her mother’s more nondescript maiden name. So when all of her activism finally landed her in court and the attorney had the gall to call her by her first name, Mary couldn’t let it go and gave him hell instead. Jailed over yet another act of civil disobedience, Mary’s 1963 hearing in Gadsden, Alabama should have been just another ordinary procedural matter. But Mary Hamilton was anything but ordinary.

“Mary, I believe you were arrested…” the prosecuting attorney started. “My name is Miss Hamilton… and I will not answer a question unless I am addressed correctly,” she quickly interjected. Her insubordination wasn’t just shocking, it was an audacious protest right in the middle of open court.

Referring to black people by first name, regardless of rank, class, educational background, or social situation was the norm before the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. Barbara McCaskill from the University of Georgia gives more context, explaining, “Segregation was in the details as much as it was in the bold strokes. Language calls attention to whether or not we value the humanity of people that we are interacting with. The idea was to remind African-Americans, and people of color in general, in every possible way that we were inferior, that we were not capable – to drill that notion into our heads. And language becomes a very powerful force to do that.” Calling grown black men and women “boy” or “girl” was another common linguistic tool that passively reinforced the American social and racial hierarchy.

Mary had endured stifling southern summers in segregated cells where the black inmates were denied air conditioning, physically invasive jail exams that amounted to sexual abuse, and so many police assaults in her pursuit of freedom that her health was already starting to deteriorate by the time she was 28. After all of that, she’d be damned if she was going to let someone turn her name into a slur.

Absolutely enraged at her calm but repeated refusals to comply until she was addressed respectfully, the judge found Mary in contempt of court that day, and her minor charge escalated to a $50 fine and 5 more days in jail. She dutifully served her sentence, and then appealed her case all the way to the United States Supreme Court. The NAACP filed documents arguing that Alabama’s use of first names perpetuated a “racial caste system” that violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment guaranteeing the same rights, privileges and protections to all citizens of the United States. The Alabama court’s transgression was so evident that without hearing a single oral argument, the Supreme Court decided in Mary’s favor, establishing the 1964 case of Hamilton v. Alabama as the legal decision that gave black adult plaintiffs, witnesses, and experts the same respect granted to white children and convicted criminals for the first time in American history.

Just a year later, Mary married out of the activism circles, but someone close to her had found major inspiration in a minor detail of her story. When Mary received a letter regarding her case, her white roommate and best friend Sheila Michaels couldn’t help but notice how the letter was addressed: Ms. “That’s ME!” she exclaimed. The honorific was rarely used, and even then, only for business correspondence where a woman’s race and marital status might be unknown, not in popular culture and most certainly not by women to describe themselves. Unmarried women in proper society were “miss” and married women were “mrs.” Mainstream language didn’t account for anyone in between. “The first thing anyone wanted to know about you was whether you were married yet,” Sheila said. “Going by ‘Ms.’ suddenly seemed like a solution; a word for a woman who did not ‘belong’ to a man.” Sheila’s campaign to popularize the term led to its adoption as the title of Ms. Magazine, and a new way to show respect was once again inspired by Mary’s work.

Despite Sheila’s best efforts to preserve the story of how Mary’s triumph lead to her linguistic epiphany, the tale of Ms. ultimately overshadowed the struggle to be called anything respectable at all. While Mary’s sharp tongue and unflinching rebellion against systematic racism ended up mostly buried in legal texts, black women today like NAACP lawyer Sherrilyn Ifill who’ve personally experienced the long “fight for respect and dignity against demeaning and ugly stereotypes in the public space” still find inspiration and courage in the woman who’d endured too much of this country’s worst to be called by anything but the best.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Read all about Mary’s life and even listen to Mary & Sheila chat together in NPR’s story & archival audio.

Dig into Mary’s first-hand account of her jailhouse treatment published in a book of letters from Freedom Riders.

The New York Times documented Mary’s historic 1964 Supreme Court win.