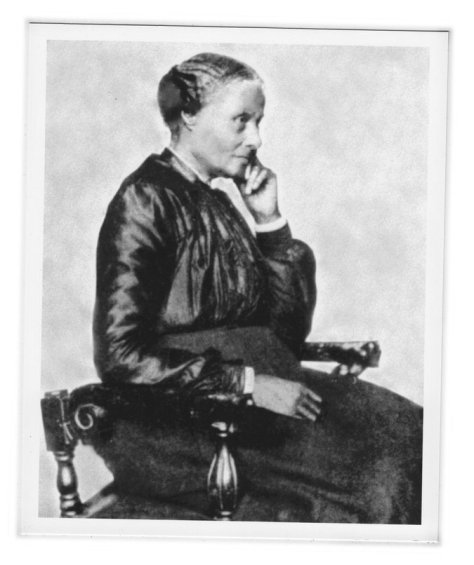

Eight interviews into the hiring process, suddenly, Stephanie Lampkin “didn’t have enough technical experience.”

By 13, she’d learned to code. By 15, she’d grown into a proficient developer. Then graduated with a Stanford University engineering degree, and an MBA from MIT Sloan School of Management, too. Her resume boasted engineering, web development and project management positions with tech giants like Microsoft, Lockheed Martin and Tripadvisor.

It was almost laughable that of all people, Stephanie Lampkin didn’t have enough technical experience. And then they dropped the punch line.

“We’ll hang onto your résumé in case a sales or marketing position opens up.”

She couldn’t have been more caught off-guard. “I thought, ‘I’ve been in computer science since I was 13. What more can I do? I have degrees from both Stanford and MIT and you’re telling me that I’m still not qualified? It was a big “aha!” moment for me.’”

Instead of looking for the right job, she’d code her way into getting the right job to look for her.

Enter Blendoor, a job-matching platform Stephanie built to eliminate unconscious bias in the hiring process, and empower companies to hire based on merit, not the majority. It provides a blind review process that removes all references to biasing demographic details – age, name, race, gender, and photos – and fills positions at diversity-minded companies with the most qualified candidates, period.

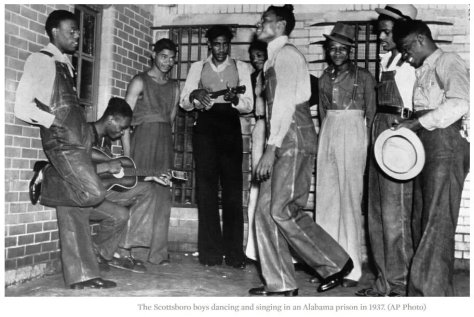

Too often, women, people of color, those with disabilities and other marginalized groups hear that companies WANT to hire diverse talent, they just can’t find it. But research indicates that the hiring pool isn’t the problem as much as the people doing the hiring are. “Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal?” an American Economic Association study asked. The answer then – and in repeated studies since – was overwhelmingly yes, with “white-sounding names” receiving 50% more callbacks than “black- or foreign-sounding names.” A joint study between Northwestern University, Harvard University, and the Institute for Social Research in Norway conducted repeatedly in multiple industries found that “at every step of the way, employers were more likely to proceed with white candidates.”

It’s a state of affairs many are aware of, but no one wants to believe is happening in THEIR organization. Stephanie disagrees. “Everybody has unconscious bias. It’s not a sexism thing, it’s not a racism thing, it’s a human thing.”

It’s the crucial insight behind removing the human element of the initial screening process altogether, and one she actually learned from an unlikely source: symphony auditions. When they began holding auditions behind a curtain, symphonies found that their gender diversity increased as much as five times that of the typical open audition. And when based on the talent alone, of course those symphonies found improved performance as well. Stephanie has replicated that model for the tech industry through Blendoor.

“I don’t want to get pigeonholed into, ‘Oh, this is just another Black thing or another woman thing,’” she says. “No, this is something that affects all of us and it’s limiting our potential.”

And what’s more, Stephanie doesn’t just empower clients like Apple, Facebook, Google, Intel, and Airbnb to diversity their hiring efforts, she empowers employees to leave their own anonymous rankings of their company’s internal inclusion efforts. With input from both sides of the equation, she’s able to solve for how each individual corporation can boost its hiring, retention and philanthropic efforts to ensure that everyone has access.

But even building her own start-up hasn’t given Stephanie immunity to the very problem she’s trying to solve. “The thing that I come up against that is always unspoken is the fact that a lot of these men haven’t seen a black woman create a product that leads to a billion-dollar valuation.” she explains. “But someone has to break through. You have to have the Jackie Robinson.., the Amelia Earhart of tech. There have been no examples of a black woman building a product, engineering a product, and making it a billion-dollar company. I’m representative of something people haven’t seen before.”

Since Blendoor officially launched in 2016, Stephanie’s not content with just tackling bias in tech. “I fear that there are many people in this world (including myself) who may never be able to reach their full potential, due to poverty, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, racism, and many other ‘isms,’” she explains. So she’s making it her business to tackle those issues everywhere, starting with venture capital where “black women lead more than 1.5 million businesses in the U.S., but received .002 percent of all venture funding in the past five years.” It’s a huge hill to climb, but if anyone can, it’s Stephanie.

After all, she’s got experience.

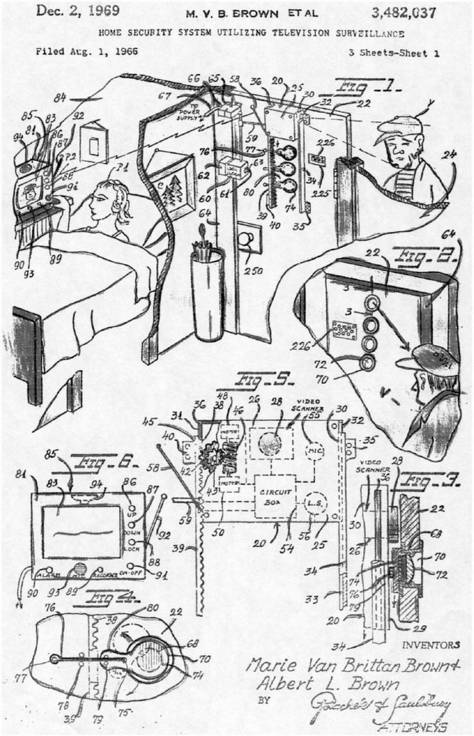

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Explore the platform & get the details on how Blendoor works.

Read Business Insider’s profile on Stephanie & what she’s up against.