“It’s just hair, it’ll grow back,” or so the saying goes.

But millions of little black girls’ and womens’ earliest memories are of their daily hair ritual beginning and ending at their parents’ feet.

And black boys, well-groomed by cultural standards, regularly submit to biased dress codes that force a choice between their educational and extracurricular activities or their hair.

Between daddy-daughter videos and the national news, Matthew Cherry saw commenters and media outlets sharing raw reactions to hallmarks of black hair as though they were novel occurrences. But in black communities, “hair is such an intimate thing,” he told Good Morning America. Where the world saw viral moments and dress code violations, Matthew saw centuries of culture, tradition, and most of all, love.

It inspired him to capture all of that emotion in a creative suite he ultimately titled “Hair Love.”

“Hair Love is more than a film. It is more than a book. It is the buoyed confidence of a little black kid. It is the flickering screen commanding the rapt attention of a little black girl who sees herself. It is the collective embrace of a young loc’d black boy discriminated against at his school. It is the ally of a progressive law,” he explains.

The CROWN Act currently being legislated in California “recognizes that continuing to enforce a Eurocentric image of professionalism through purportedly race-neutral grooming policies that disparately impact Black individuals and exclude them from some workplaces is in direct opposition to equity and opportunity for all.” Its language is intended to extend to housing and school codes for full protections against the policing of black hair in any government-regulated setting.

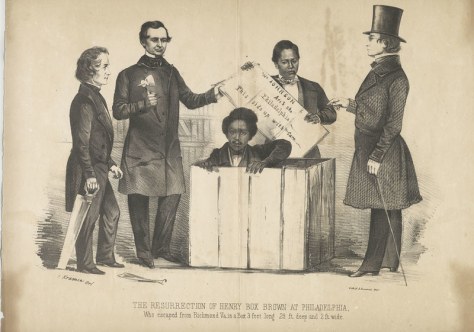

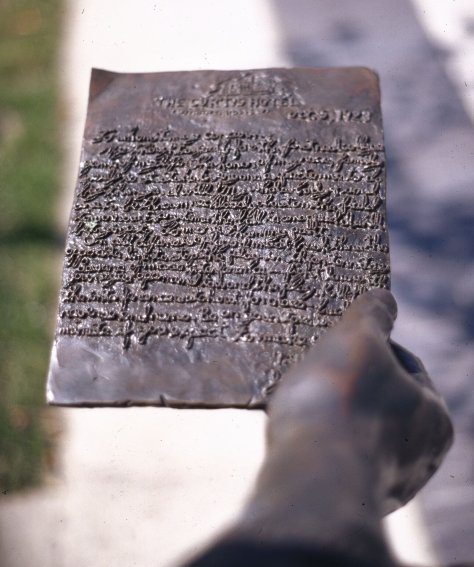

The irony of that legislation isn’t lost on black Americans familiar with 18th-century “Tignon Laws” that attempted to dehumanize black women by forcing them to cover their hair under penalty of arrest, but ultimately backfired when their extravagant hair wraps became fashionable and coveted by everyone. Past and present, hair that’s regulated, exoticized, appropriated and misunderstood also runs deep throughout the history of black American culture.

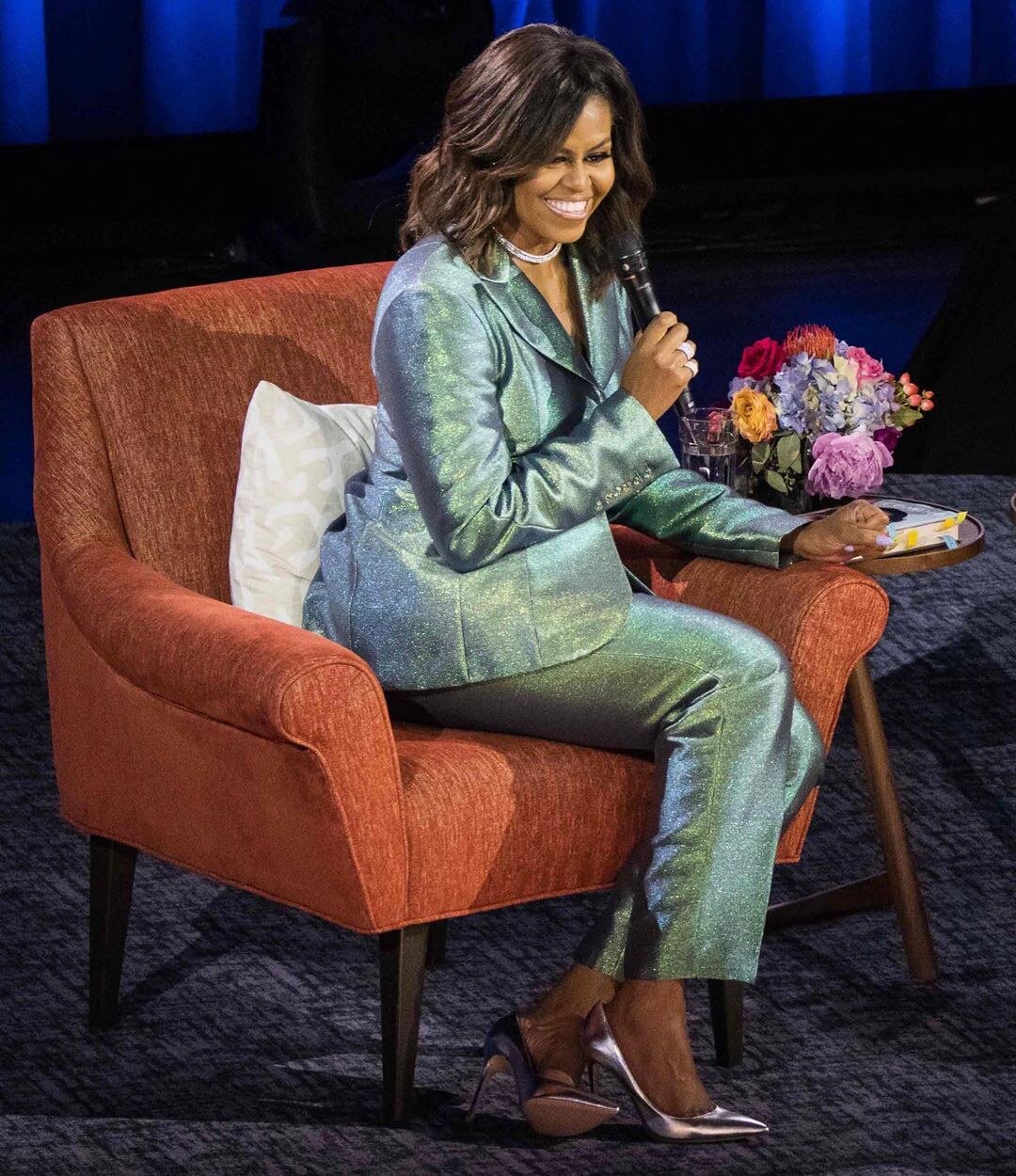

So it’s no wonder that when Matthew pitched it to her, Sony Pictures Animation’s Executive Vice President of Creative (and black woman) Karen Rupert Toliver saw something truly special in “Hair Love” and the universal black experiences it communicated – something she knew had to be shared. “I think images are so important to changing people’s perceptions [of others] and changing their own perceptions of themselves,” she says. And Matthew agreed that “if you focus on how you’re affecting the culture and you’re affecting change… even if [awards] don’t come, you’re still doing great work.”

But tonight, at a ceremony with fewer black nominees than it’s seen in the last 3 years, The Academy Award for 2020’s Best Animated Short DID come.

For a not-quite-7-minute short that Matthew created for the purpose of “see[ing] more representation in animation, but also wanting to normalize black hair,” this evening’s win was monumental in the hearts of black people, in the extremely white landscape of the Oscars, and surely in the future history books of a country still learning through the centuries that “just hair” can mean so much more.

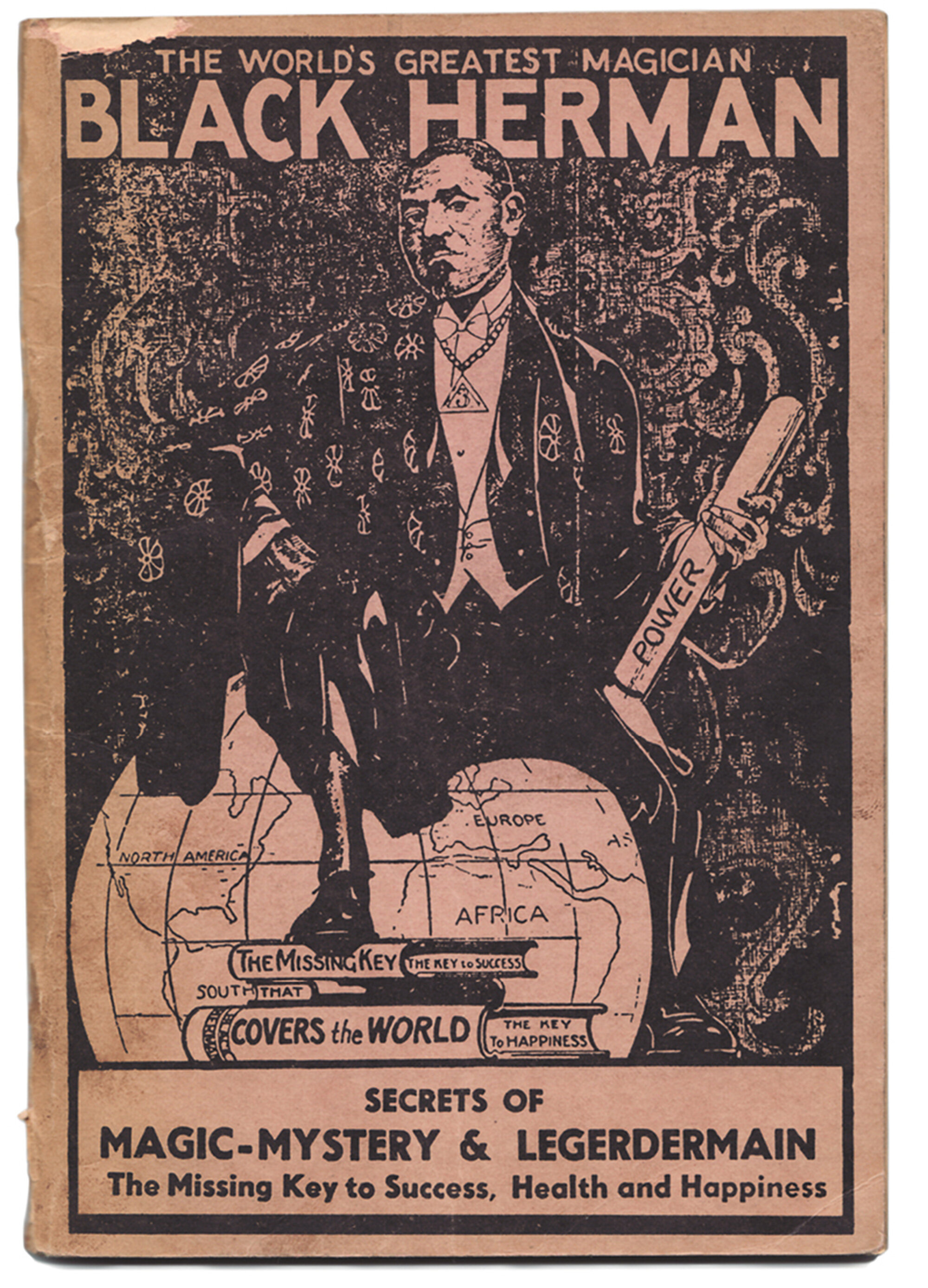

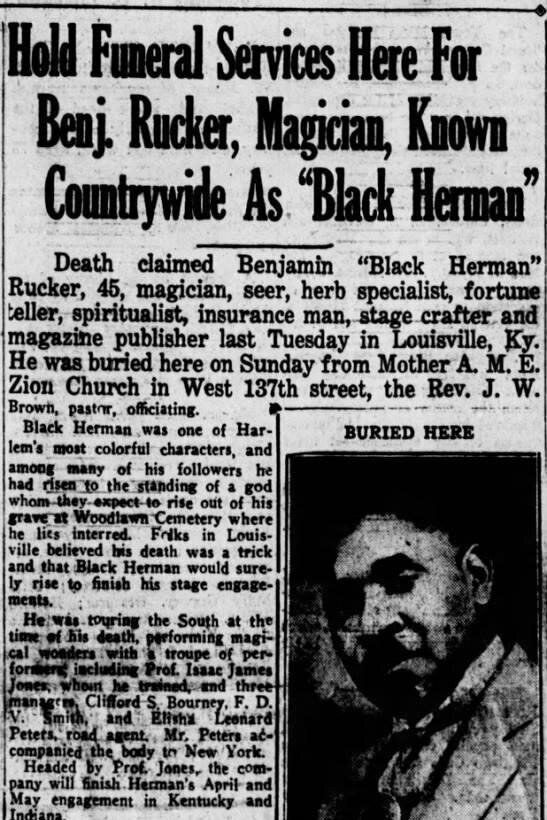

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY: