Only a handful of places immediately come to mind as somewhere a hat can transcend accessory to become ceremony.

Royal weddings and the Kentucky Derby have their own hat stories, but they’ve got nothing on the history and tradition a hat carries atop an African-American woman’s head.

Flash back to the Middle Passage, 1518.

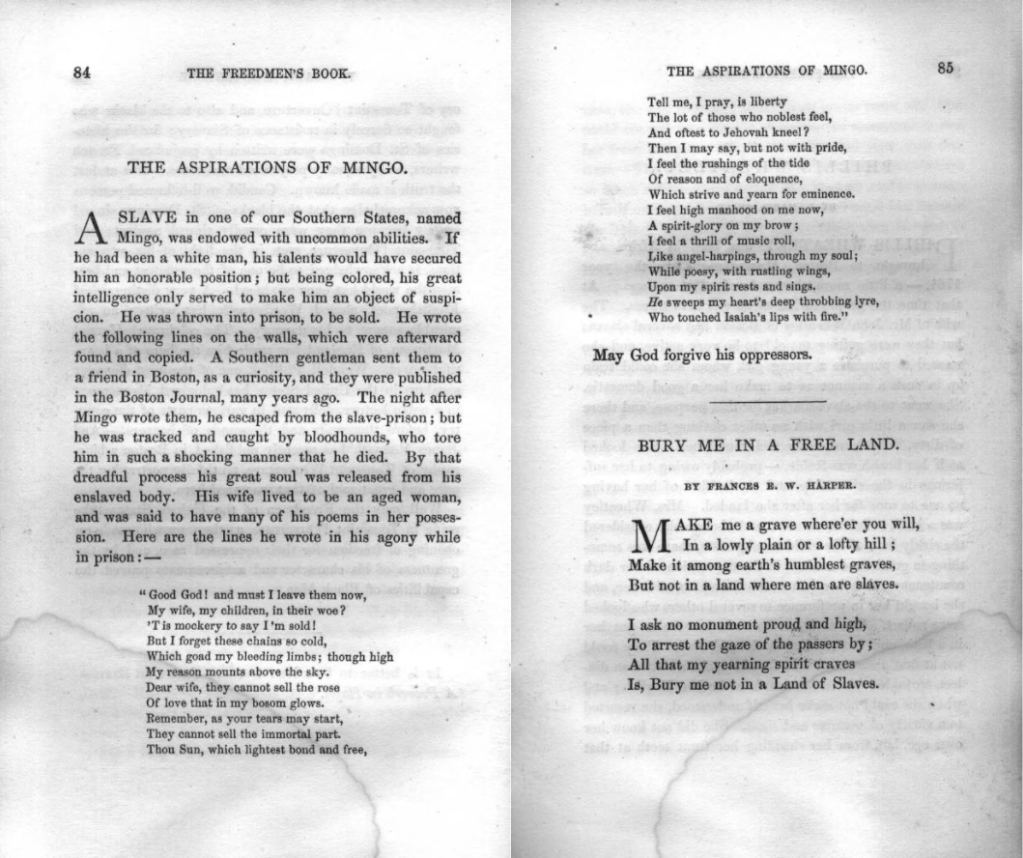

Before Africans were transported on ships to the British Empire, the Americas, and all over the colonized world, they were shaved bald. Officially, shorn heads prevented lice and the sanitation issues bound to arise when people are chained in excrement.

But there’s more to the story. Shaving a person’s head is the easiest way to dehumanize them. Throughout the centuries, it’s been used as a tool of war, degradation, and shame. The mighty Sampson lost his identity when his hair was shorn. Even Nazis knew to shave and commodify their captives. And American slavers did the same, profiting from the hair, teeth, and even living bodies of the enslaved.

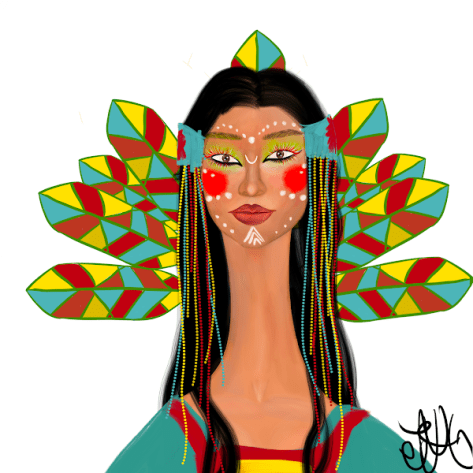

But on glorious Sundays, away from the strict eye of their captors, the enslaved could adorn their shaved heads in any way they pleased. The hair once decorated with beads, shells, feathers and dyes in Africa, was replaced with elaborately tied wraps, some of which used techniques that had been carried across the Atlantic. Community and individuality were both reclaimed, all in a single piece of fabric.

Flash forward to the French colonies, 1685.

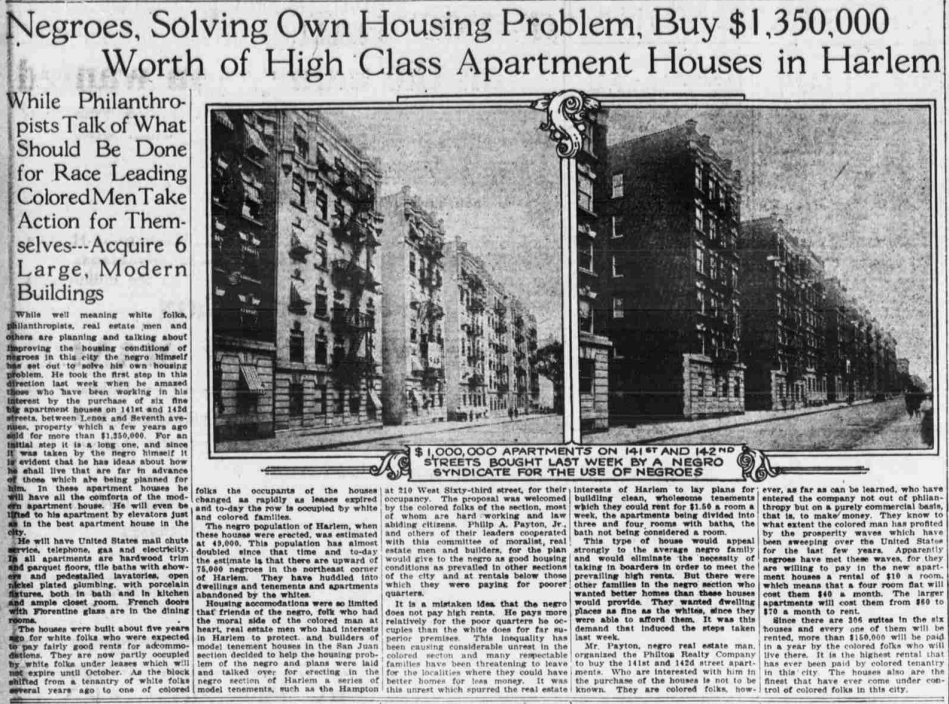

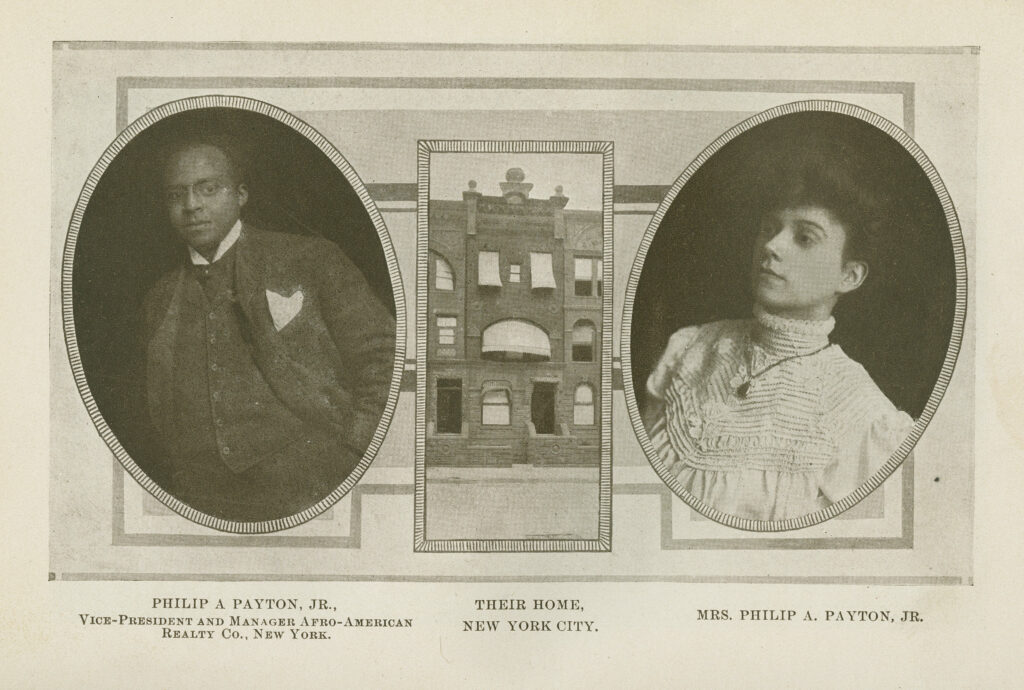

The French held a great deal of land in what’s now North America, and enacted the Code Noir enforcing specific (and outrageous) rules on the conduct of Black people throughout their colonies. In 1786 Louisiana, Code Noir was made even more outrageously specific when the governor, lobbied by his white female constituents, ordered that all women of color, free or enslaved, must cover their hair with a scarf or handkerchief called a tignon, devoid of any added embellishments like feathers or jewels. You see, white enslavers had so abused Black women that it had gotten hard to tell who was who anymore. A fair-skinned, well-dressed woman could be an upstanding white woman, a free Black woman, or the slave girl of a wealthy French family, and of course, treating them all the same would be disgraceful. Forcing only enslaved women to cover their hair would create visible classes among Black women, and that wouldn’t do either because the whole point of Tignon Law was to prevent Black women from thinking too highly of themselves and presenting themselves accordingly. Actually, the governor’s exact words were “too much luxury in their bearing.”

Those actions backfired in the biggest way when tignons caught the eye of one Empress Josephine Bonaparte who began wearing her own as a fashion accessory. The tignon turned into a trend, and the racist society snobs of Louisiana were right back to square one.

Flash forward to modern day Civil Rights, and today’s story.

African-American churches were the lifeblood of the movement. There, boycotts were organized, flyers were printed, and the people were fed, physically and spiritually, throughout their tireless fight. Those churches were also the only place African-Americans could truly serve as leaders in a culture where work, school, and leisure were segregated. African-American women in particular acted as pioneers and again, head coverings played their part. Women in leadership roles or married to leaders needed to be identifiable among crowds of their congregations and onlookers. A beautiful hat is also a symbol of dignity, status, and taste. Women who marched in the Montgomery Bus Boycotts came dressed not in their typical domestic uniforms, but in their Sunday best, knowing the optics of both their personal presentation, and of violence against a church-going woman. Nothing speaks to religious piety, humility and grace like a woman with her head covered. And when you couldn’t change your skin color, the one thing you could change was your clothes.

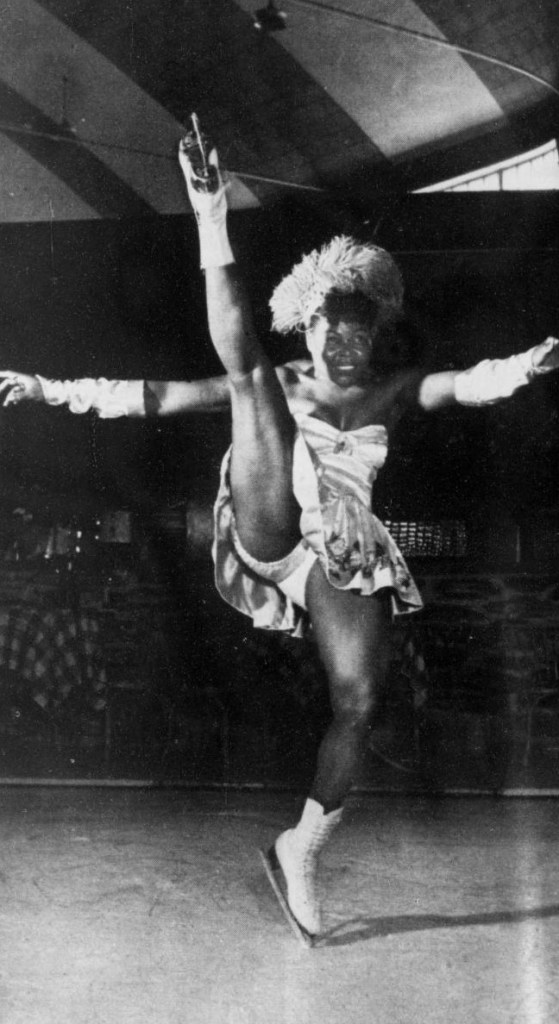

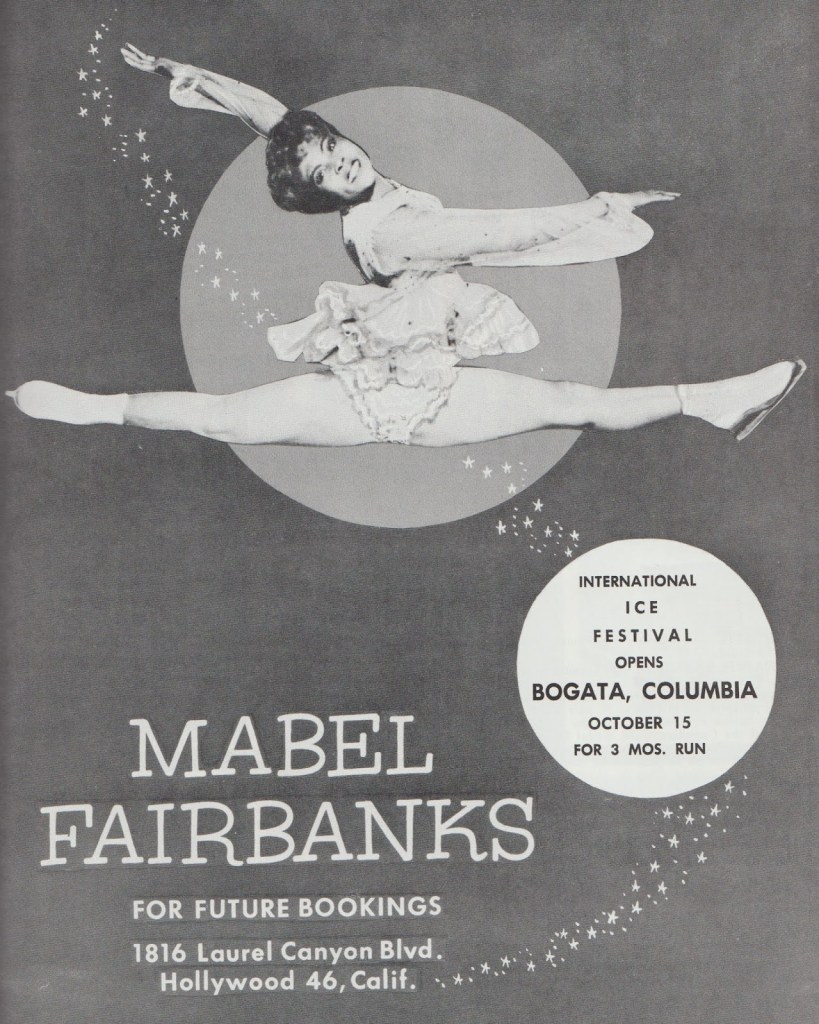

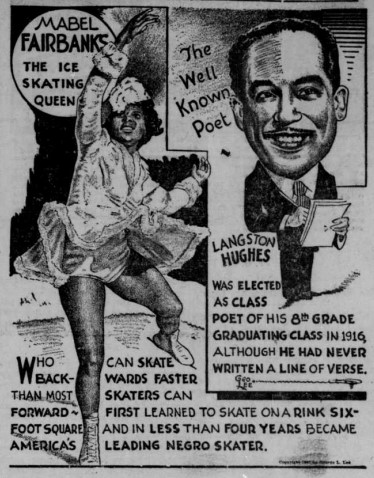

Civil rights pioneer Dorothy Height knew all of this, and there was only one lady she trusted to capture all of that history for her: Vanilla Powell Beane.

If you’ve ever seen a photograph of Dorothy, you’ve almost certainly seen Mrs. Vanilla’s handiwork.

In 1950s Washington D.C., Mrs. Vanilla was barely out of her 20s, just a working woman with no grand designs towards civil rights, history, or fashion. She didn’t even have hat-making experience. “I [worked] in a building where they sold hat materials, so I bought some and decided to see if I could do it.”

Today, she’s the 102 year old proprietor of Bené Millinery & Bridal Supplies, having built a reputation as hat maker to not only Dorothy Height, but other past and present African American women in power like D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser and poet laureate Maya Angelou.

Her shop opened in 1979 and prior to COVID shutdowns, Mrs. Vanilla still worked 40+ hours per week, crafting hats and styling customers. When she started making hats, segregation and Jim Crow was still very real. But today, her diverse range of hatwear sits atop a diverse range of heads, and she’s glad to teach any woman her “rules”: “Don’t match the hat to the outfit. Just buy a hat you like and the outfit will come. Never wear your hat more than one inch above your eyebrows. Slant it to look more interesting and possibly even risque.”

“She’s at the shop six days a week, and whenever we celebrate her birthday, she typically wants to stay open so people can stop by and get a hat to wear to the party,” Mrs. Vanilla’s granddaughter Jeni Hansen said. Mrs. Vanilla wholeheartedly agrees that it’s the shop and customers that have kept her going. At her age, she’s seen, experienced and overcome so much, including the deaths of her husband and son along the way, and of course most recently, a global pandemic affecting small businesses like never before. But Dr. Dorothy Height’s mother Fannie once said, “No matter what happens, you have to hold yourself together.”

Through Bené Millinery and her extraordinary work in a slowly dying art, Mrs. Vanilla has held herself—and the D.C. African-American culture together through hats, and thankfully, shows no signs of hanging up her own.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Inspect one of Mrs. Vanilla’s favorite hats in interactive 3D at the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History & Culture.

Artist Ben Ferry was so delighted to meet Mrs. Vanilla in her shop that he created a whole art collection featuring the lady herself, her work, and her shop. The cover image for this post shows Mrs. Vanilla posing next to Ben’s work. See the collection here, and read the story of how these two opposite creatives attracted here.

September 19 was designated “Vanilla Beane Day” in the District of Columbia. Read the full proclamation, issued on Mrs. Vanilla’s 100th birthday, here.

Bené Millinery is still working to get online, but in the meantime, browse around and plan an in-person visit by appointment on their website.

Learn more about the history of Black hair, its care and its coverings around the globe and throughout the diaspora at BET.

It’s still not illegal to discriminate against a Black woman’s natural hair in the United States. Find out more about the steps being taken to pass The CROWN Act nationwide.