The Third Avenue Trolley conductor had no idea he’d picked the right one on the wrong day.

The organist for New York’s First Colored Congregational Church was running late for Sunday service.

But in her haste, Lizzie Jennings almost single-handedly desegregated the New York Public Transit system…

A full century before Montgomery met Rosa Parks.

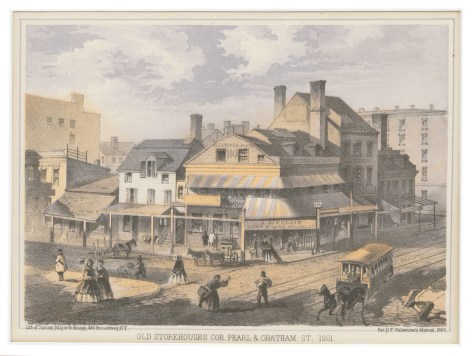

Two types of horse-drawn trolleys operated in the streets of New York: one was designated “colored riders allowed,” and the other’s ridership was left to the whims of the operator and his white passengers.

One trolley ran a regular, timely schedule. Guess which one did not?

New York’s Black citizens had two choices: wait or walk.

On July 16, 1854, Lizzie Jennings didn’t have time for all that and boarded the first trolley she saw.

The operator still tried it.

Wait for the next car, he told her.

But she was in a hurry, Lizzie replied.

That one’s got your people, he persisted.

What people? Lizzie spouted back.

A car that allowed Black riders came and went because it was full.

Lizzie sat unmoved.

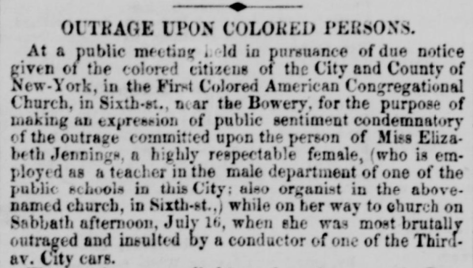

“He still kept driving me out or off the car,” Lizzie explained in her account published in the New York Tribune. “Said he had as much time as I had and could wait just as long.”

“I replied, ‘Very well. We’ll see.'”

The trolley operator’s eventual surrender came with a disclaimer: “if the passengers raise any objections, you shall go out… or I’ll put you out,” Lizzie wrote.

Quick to clap back, she “answered again and told him I was a respectable person, born and raised in New York, did not know where he was born and that he was a good-for-nothing impudent fellow for insulting decent persons while on their way to church.”

Big NYC energy from a little lady in 1854.

So big, the operator tried to physically remove her.

Lizzie grasped onto the window, his coat, anything within reach to keep from being forcibly removed. They scuffled for several minutes before the operator called on the trolley’s horse driver for an assist.

If they were going low, she’d meet them in hell.

“I screamed ‘murder’ with all my voice.”

The pair finally resorted to driving the trolley to the nearest police officer, with Lizzie kicking and screaming the whole way.

Pushing her onto the ground, the officer sneered at her to “get redress if [she] could.”

So she did. Remember when I said Lizzie was the right one?

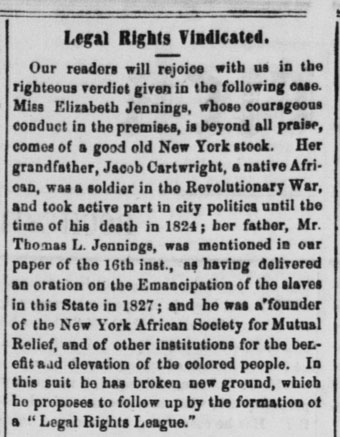

Elizabeth Jennings was the daughter of Thomas Jennings, the first Black person awarded a United States patent, owner of a profitable tailoring business, and a founder of THE Abyssinian Baptist Church, currently active in Harlem.

Her paternal grandfather had connections to Frederick Douglass’ Paper, and Lizzie’s personally written account of her mistreatment was published there, The New York Tribune, and many other abolitionist papers.

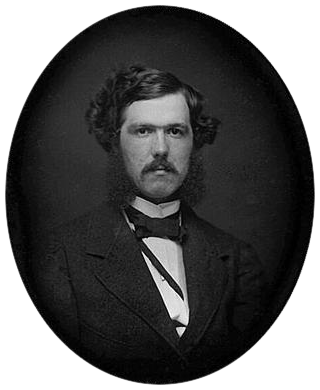

Lizzie’s powerful network didn’t stop there. They brought a 24-year-old upstart fresh out of law school to her door.

That man’s name was Chester Alan Arthur, future 21st President of the United States.

Against an all-white, all-male jury, Lizzie & Chester did the seemingly impossible: THEY WON.

Lizzie was awarded cash damages from the Third Avenue Railroad Company, but more importantly, an agreement to desegregate their trolleys, effective immediately.

“Railroads, steamboats, omnibuses, and ferry-boats will be admonished from this, as to the rights of respectable colored people,” The Tribune wrote.

Those who ignored the judgment weren’t far behind on the Jennings’ War Path.

The Legal Rights League, formed by Lizzie’s father Thomas, challenged every last New York transit hold out until in 1861, just seven years after Lizzie’s impromptu sit-in, ALL of them were finally desegregated.

After her case was won, Lizzie largely retreated into ordinary life, but she didn’t stop being an extraordinary person.

Until her death in 1901, Lizzie operated New York’s first kindergarten for Black children from her home.

All that history from a lady who just wanted to go to church, and hardly anybody knows her name.

But the city of New York is working to change that. There’s already a section of Park Row near her historic ride, dedicated to Elizabeth. She Built NYC, an arm of the NY Department of Cultural Affairs has fully funded five statues honoring trailblazing New York women.

Elizabeth Jennings is one of them.

As for the trolley operator, the horse driver and the policeman who abused her? They’ve virtually disappeared from history.

Maybe somebody should check with their people.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Lizzie is one of many famous New Yorker’s whose life and death were overlooked by the Times until modern days and their article on her here.

Read over Elizabeth’s first-hand account published in the NY Tribune at the Library of Congress.

Read The Search for Elizabeth Jennings, Heroine of a Sunday Afternoon in New York City for FREE at JSTOR.

STILL can’t get enough Elizabeth? Visit Dr. Katharine Perotta’s award-winning Elizabeth Jennings Project.