The major difference between racial terrorism in the North and the South was the publicity.

Escape to the North and you may avoid a spectacle of a lynching, but that still didn’t make you welcome.

Take the case of Harlem, NY.

Now considered one of the most historic African-American communities in the United States, it was once entirely white and there were a lot of folks invested in keeping it that way.

Real estate investors, to be specific.

The neighborhood just north of Manhattan was booming in the late 1800s. Oscar Hammerstein’s first opera house, the world’s largest gothic cathedral in St. John the Divine, and Columbia University all opened or began construction in Harlem within 8 years of each other. Property was being snatched up left and right to support new expensive apartments, some priced up to 800% more than those in Manhattan. Harlem was destined to be the height of luxurious living.

But the city was growing everywhere, and by 1904, developers and dwellers were already on to New York’s next hotspot. All those high-dollar rents were plummeting as whole buildings purchased in anticipation of continued growth suddenly stood empty.

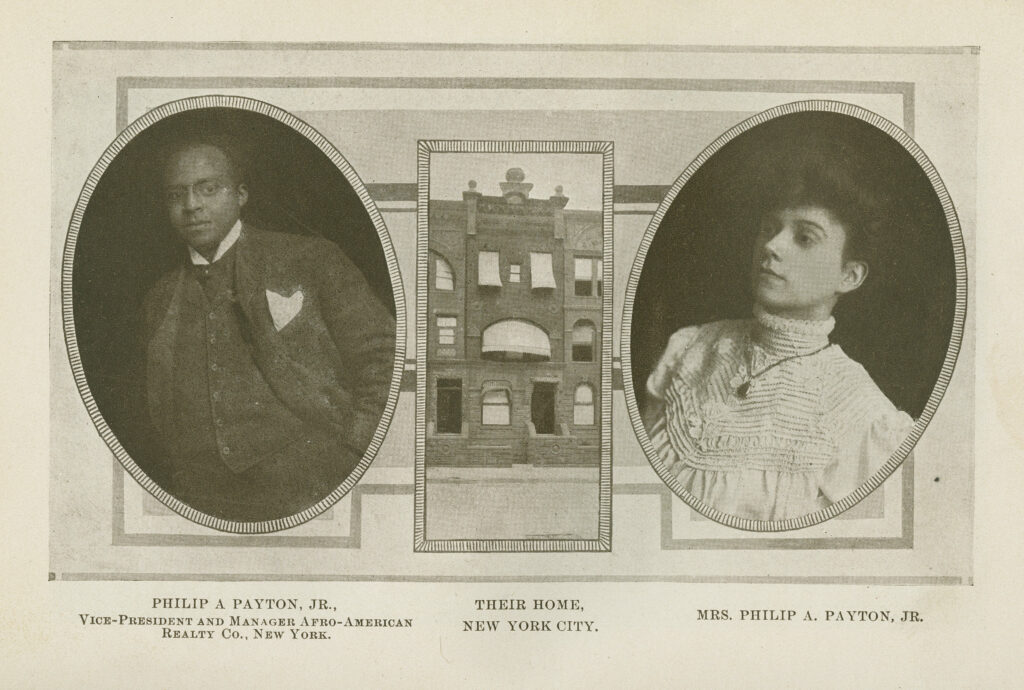

But Philip A. Payton Jr. had been biding his time. After a few odd jobs and small business ventures, he’d discovered a passion for real estate. And then spent his last dime on classified ads.

“COLORED TENEMENTS WANTED | Colored man makes a specialty of managing colored tenements; references; bond. | Philip A. Payton, Jr., agent and broker, 67 W. 134th.”

Whatever property did come his way would have to come cheap. And racism was about to get Philip out of the red.

“My first opportunity came as a result of a dispute between two landlords in West 134th Street. To ‘get even’ one of them turned his house over to me to fill with colored tenants,” Philip recounted to the New York Age.

The race to own Harlem was on. With a few rent payments in his pocket, Philip purchased even more luxury properties at rock-bottom prices to pass on to new, Black tenants.

And the locals were not happy about it. White New Yorkers weren’t willing to share their space with people of color and their white brokers knew it. If things kept up at this rate, they’d have even more empty buildings on their hands, so the brokers started biding their time too. The second Philip sold some of his predominantly African-American tenements to free up some cash, the white brokers snatched it up, evicted his tenants, and made the buildings white-only again.

Well, Philip knew how to be slick too.

Two buildings managed by those white brokers were up for sale on the same row, sandwiching the ones he’d sold. He bought those two buildings, evicted all of the white tenants, replaced them with Black ones, and created the exact crisis the white brokers were trying to avoid. Suddenly in the middle of a Black block, the white tenants fled and their brokers had to put the buildings back up on the market.

Guess who bought them for even less than he sold them for.

In the midst of all of this buying and selling, Philip recognized that he couldn’t take on the entire Harlem real estate establishment, so he formed an organization that could. On June 15, 1904, the Afro-American Realty Company was chartered and funded. With 50,000 shares issued at $10 each to wealthy African-Americans, the Afro-American Realty Company bought properties throughout the neighborhood, turning Philip’s vision into whole blocks of thriving Black families.

He saw Black folks using the circumstances stacked against them to come up. The New York Times saw a “Real Estate Race War.”

The Afro-American Realty Company didn’t last, but the trend did. Philip opened the Philip A. Payton Jr. Company, and spurred by his continued success in the neighborhood, many of Philip’s former AARC co-investors followed suit. By 1905, newspapers reported on the shifting demographics in Harlem like a plague had descended. “An untoward circumstance has been injected into the private dwelling market in the vicinity of 133rd and 134th Streets.” the New York Herald reported. “Flats in 134th between Lenox and Seventh Avenues, that were occupied entirely by white folks, have been captured for occupation by a Negro population… between Lenox and Seventh Avenues has practically succumbed to the ingress of colored tenants.”

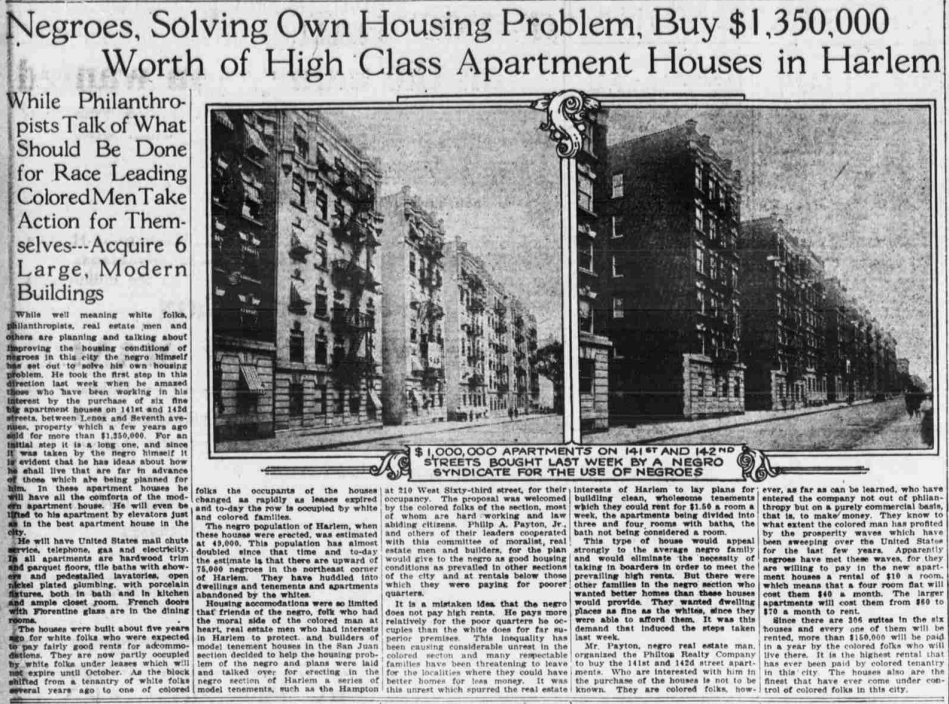

Though their language left something to be desired, the Herald wasn’t wrong about the tidal wave of African-Americans who seemed to own Harlem overnight. By 1915, just over a decade after Philip first moved to an all-white block himself, census records showed nearly 70,000 Black residents had moved in right behind him. In 1917, he officially staked his claim in Harlem with the biggest purchase of property by Black broker that New York had ever seen. Philip bought six buildings at $1.5 million, naming them all for historic Black figures, building more community from that sense of pride.

For his lifetime of groundbreaking development, Philip was called the “Father of Harlem,” and though he died at 41 years old, just a month after his historic $1.5 deal, the foundation he laid lived on. It’s no coincidence that in 1920, the Harlem Renaissance officially began. Even the National Institutes of Health recognize that psychological safety—”the belief that you won’t be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes”—leads “to increased proactivity, enhanced information sharing, more divergent thinking, better social capital, higher quality, and deeper relationships, in general, as well as more risk taking.”

Free from the fear of their homes falling under constant threat from the whims of white people, whether they were southern night riders or northern bankers, African-Americans finally had the luxury of creating something beautiful, and in doing so, absolutely changed the world.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Though the New York Times ran articles about him and what he was doing in Harlem, their Overlooked series is the first to truly acknowledge its positive impact.

Philip wasn’t the only wildly successful Payton. Read through an accounting of his accomplishments, as well as those of his siblings at Westfield State University in the town where the Paytons once flourished.