On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln wrote:

“I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”

Having finally received “unalienable” rights and having witnessed the admiration bestowed upon white soldiers over the course of 4 separate wars, many African-American men were hopeful that enlisting and serving the United States by choice would force Americans to think better of the whole race.

But the words of the Emancipation Proclamation couldn’t sway the hearts and minds of men, especially when those words were undermined by another sitting president.

When the Buffalo Soldiers, went to battle on behalf of the U.S. Army in the Spanish-American War, Rough Rider Frank Knox said, “I never saw braver men anywhere.” Lieutenant John J. Pershing wrote, “They fought their way into the hearts of the American people.” President Teddy Roosevelt went on record saying “Negro troops were shirkers in their duties and would only go as far as they were led by white officers.”

Less than a decade later, the Harlem Hellfighters would make him eat crow.

When the United States joined the war against Germany, they did so woefully underprepared. American military forces had never gone to battle overseas before, and the Army’s ranks of a mere 126,000 men wasn’t going to cut it. Of the Armed Forces that existed at the time, only the Army allowed African-Americans to enlist for combat, even though it was hardly on an equitable basis. There were only 4 “colored regiments” and once their ranks were filled, the rest of the Black applicants who’d lined up for service were turned away. When Selective Service began in 1917, men of color were told to tear a corner of their draft card away so they could be easily identified and assigned. In the thick of World War I with the Central Powers devastating Allied forces in Europe, U.S. draft boards used those torn corners to send as many Black men to the front lines as they could.

The men of the 369th Regiment however, scrubbed toilets stateside when they first enlisted, relegated to menial and filthy tasks like slaves, even though they’d volunteered for service. But when the war demanded more soldiers, the 369th went from toilets to trenches , being upgraded to Infantry, and shipped off to France for three weeks of combat training before being stationed on the war’s front lines.

But even there, they weren’t considered “soldiers.” White Col. William Heyward begged that the 369th be allowed to actually serve on the battlefield, rather than dig trenches, unload ships, and other manual labor they’d been assigned to, as if nothing had changed at all. Army command compromised, assigning the 369th to the French Army instead.

When it came to the 369th and many other all-Black regiments, the Army didn’t send soldiers or reinforcements, they sent human shields expected to die. They never dreamed that the 369th would gain the respect of the French, who’d nickname them “Hommes de Bronze,” or come to be feared by the German Army who first dubbed the 369th as Hollenkampfer (“Hellfighters”). The Army most certainly didn’t expect that the 369th Regiment would be the very first Allied force to breach Germany’s borders.

But the Army wasn’t entirely wrong. The Hellfighters spent 191 days in combat, more than any other unit in the war and suffered losses to match, with hundreds dead and thousands wounded over the course of their deployment. Those losses were deeply felt by Captain Arthur Little who wrote, “What have I done this afternoon? Lost half my battalion—driven hundreds of innocent men to their death.” Those who survived fought their way to becoming some of the most decorated American soldiers in history… by another nation. The entire 369th Regiment was awarded the Croix de Guerre, the French Medal of Honor, and over 170 of its servicemen were honored individually. The Hellfighters Band was even honored, being largely credited as Europe’s first introduction to jazz.

Sgt. Henry “Black Death” Johnson earned a personal mention in the war dispatches of Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the entire American Expeditionary Forces and the same man who, in the words of Col. Heyward, “simply put the black orphan in a basket, set it on the doorstep of the French, pulled the bell, and went away.” With only a bolo, 5-foot-4, 130 pound Sgt. Johnson single-handedly defended himself and his wounded partner against armed German soldiers who raided an Allied outpost. President Roosevelt would later name him as one of the “five bravest Americans” of World War I.

Thousands of New Yorkers welcomed the veterans of the Hellfighters home.

And then forgot them altogether.

In the best cases, the Hellfighters drifted back into their lives, and lived in relative anonymity. In the worst cases, like those of Lawrence Leslie McVey, their remarkable service earned them a death by beating in the streets of New York.

Despite all of those medals abroad and the pretty words spoken, the United States didn’t award the 369th Regiment anything until 2015. By then, no one survived to accept the Congressional Medal of Honor awarded to Sgt. “Black Death” Johnson who was injured in combat 21 times. On August 21, 2021, the entire unit was finally recognized posthumously with a Congressional Gold Medal, awarded since the American Revolution as the country’s “highest expression of national appreciation.”

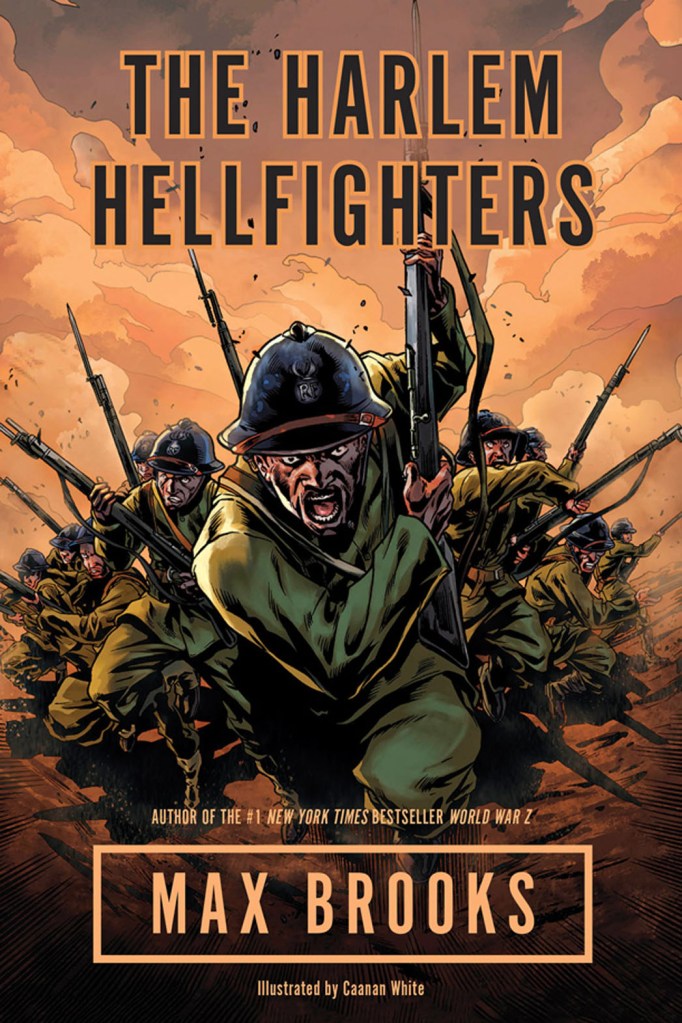

Tomorrow, February 11 will be the anniversary of the Hellfighters’ return to the States. The 3,000 men who marched Fifth Avenue that day were only a small portion of the “25 percent of Americans fighting in France [as] hyphenated Americans,” according to Lt. Col. ML Cavanaugh and Max Brooks (yes, World War Z Max Brooks), fellows at West Point’s Modern War Institute. Those other 25% included Choctaw code-talkers whose language was unbreakable abroad, Chinese Americans, Latinos like “Pvt. Marcelino Serna, a Mexican American who migrated to El Paso before the war, took out an enemy machine gun, a sniper, and an entire German platoon on his own, becoming the most decorated Texan of World War I,” and so many more who’ve been forgotten.

I hope you’ll spend the day paying tribute to those Americans who didn’t let the hyphens and racism visited upon them by others stand in the way of sacrifice and the fight for their own unrealized freedom.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Read the National Museum of the United States Army account of the wars the Harlem Hellfighters fought at home and abroad.

Smithsonian Magazine features more personal details of the lives, accomplishments and times of the Harlem Hellfighters.

Browse the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture’s “Double Victory: the African-American Military Experience” here.