The President may issue each year a proclamation designating February 1 as National Freedom Day to commemorate the signing by Abraham Lincoln on February 1, 1865, of the joint resolution adopted by the Senate and the House of Representatives that proposed the 13th amendment to the Constitution.

U.S. Code § 124 – National Freedom Day

But in 1853, Henrietta Wood couldn’t afford to keep waiting.

Until that year, her life had not been unlike that of most African-Americans. Henrietta was born into slavery around 1818 in northern Kentucky, worked for one master until he died, was sold to another, relocated elsewhere, rinse and repeat.

Until the day in 1844 when one of her masters, a merchant and French immigrant took leave from his New Orleans estate, and its mistress stole Henrietta away to the free state of Ohio, seeking to make her own fortune by hiring Henrietta out to Northerners in need of help. That plan backfired as creditors left high & dry in New Orleans saw Henrietta’s value too. Rather than allow her to be seized as an asset, the mistress begrudgingly granted Henrietta’s freedom.

And for nine years, Henrietta savored it. But unwilling to let their dowry slip away, the master’s daughter and son-in-law hired Zebulon Ward, a notorious Kentucky deputy sheriff, slave trader, and future Father of Convict Leasing, to kidnap Henrietta back across state lines.

Despite her status, The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 legislated Henrietta’s silence. Under its rule, enslaved people were not entitled to a trial, and were forbidden from speaking in their own defense should they obtain one. Adding insult to injury, Federal commissioners overseeing these sham proceedings were paid $10 for every person they deemed a fugitive, but only $5 for every freedman. Anyone mounting a case against the system was already at a loss.

But against those insurmountable odds came an intervention. John Joliffe—the same lawyer who’d defended Margaret Garner—argued a 2-year long lawsuit on Henrietta’s behalf. And once more, freedom seemed futile. The Cincinnati courthouse where Henrietta’s papers had been filed had burned to the ground, and any hope of defense with it.

She’d spend the next 14 years re-enslaved, sold this time to Gerard Brandon, the son of a Mississippi governor, in 1855. With the Brandons, freedom would only continue to be snatched from Henrietta’s grasp. Afer the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, Master Brandon marched all 300 of his slaves over 400 miles to Texas where it’d take Union soldiers another 2 years to arrive on June 19, 1865.

But papers and proclamations hardly made enslaved people free, and Henrietta was living proof. Slavery was still legal in many islands off the coast of the United States, and her own story demonstrated the lengths that slavers would go to profit off “free” human beings. Henrietta reluctantly accepted a formal employment contract from the Brandons promising $10 a month, which she held was never actually paid. Either way, the score was far from settled, her worth was much higher, and Henrietta had every intention of pursuing both.

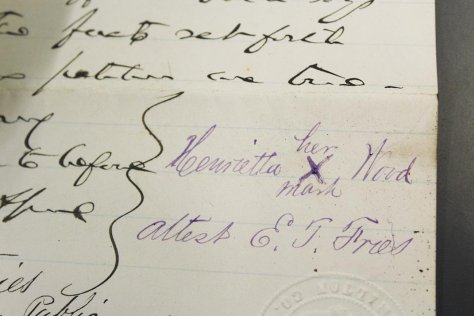

In 1878, Federal Judge Philip Swing presided over Wood vs. Ward, where the plaintiff sought $20,000 in restitution for her kidnapping and re-enslavement. Black people weren’t allowed to sit in juries until a 1935 case brought to the Supreme Court by one of the Scottsboro Boys made it illegal to systematically exclude Black people from service (note: systematically). So the notion that an all-white jury would see fit to award a formerly enslaved woman without documentation any dollar amount was likely more about the principle than the actual court judgment.

We the jury on the above titled cause, do find for the plaintiff and assess her damages in the premise of Two thousand and five hundred dollars $2500. (signed), Foreman.”

But in 1879, twenty-six years after Henrietta was sold back into slavery, a jury handed down $2,500—nearly $90,000 today—the highest dollar amount ever awarded by a court in restitution for enslavement.

That award funded her son Arthur’s college education. Born early into Henrietta’s re-enslavement, Arthur Simms had also lived on both sides of freedom, and took full advantage of his newfound rights. In 1889, he graduated as the first Black man to earn a degree from Northwestern University’s Union College of Law, and died as the school’s oldest living alumnus in 1951 at 95 years young, a testament that true freedom keeps paying dividends.

Happy Freedom Day & Happy Black History Month, y’all. Let it ring.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

W. Caleb McDaniel, the same historian who allied against Fort Bend ISD in support of preserving the Sugar Land 95 uncovered Henrietta’s story. Read his take on her story and interact with Henrietta’s route to freedom at the Smithsonian.

Mr. McDaniel continued over at the New York Times, explaining how Henrietta’s case has re-opened a “dark chapter in American history that in many ways remains open.”

McDaniels’ book Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America won a 2020 Pulitzer Prize. Read an excerpt at the National Endowment for Humanities and see more about Harriet’s case at the book’s page.

In 1876, Henrietta told her own story to the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper. It’s collected here in four parts and is the most complete accounting of her story that survives.

Even Henrietta’s descendants didn’t know about her until Mr. McDaniel shared her incredible story. Read how they put together the pieces, and unknowingly, made her fight for freedom “worth it.”

2 thoughts on “DAY 1 — Henrietta Wood”

Comments are closed.