Police swarmed the King’s Terrace nightclub in midtown Manhattan. Some upstanding citizen had reported a terrible crime in progress that 1934 night. A “masculine garbed smut-singing entertainer” and her “liberally painted male sepians with effeminate voices and gestures” were traipsing around the stage and right through the audience performing songs so lewd the devil himself would blush.

On the other hand, through the eyes of renowned black poet Langston Hughes, that same performer was an “amazing exhibition of musical energy – a large, dark, masculine lady, whose feet pounded the floor while her fingers pounded the keyboard – a perfect piece of African Sculpture, animated by her own rhythm.”

From the beginning, Gladys Bentley – or Bobbie Minton, depending on where you knew her from – seemed to have a knack for being different things to different people.

A full figure that she clothed in men’s attire, her reputation as a tomboy, and schoolgirl crushes on female teachers were the earliest indicators that Gladys was different from the other girls. Her parents sent her to specialist after specialist to be “fixed,” but when Gladys was 16, she fled their closed-minded Philadelphia home to find a new family in Harlem instead.

She arrived in 1923 during the Renaissance, and after a handful of small gigs around town, an opportunity that seemed tailor-made for her presented itself. The owners of The Clam House, one of Harlem’s most famous gay speakeasies, needed a new man as their sister bar’s nightly pianist, and as far as Gladys was concerned, she fit the qualifications. “But they want a boy,” a friend scolded her. “There’s no better time for them to start using a girl,” Gladys quipped. She arrived at her audition with her hair slicked down and in the finest suit a runaway teenager could find, where she proceeded to bring the owners, the staff and everybody within earshot to their feet in a standing ovation.

There could have been no better validation. But then again, when it came to validation for society’s free-thinkers, there was no better place than Harlem. During the Renaissance, creative, curious and ambitious black minds flocked to Harlem to join the growing collective of visual, performing and written artists flooding the American consciousness. The influx of those new ideas and Harlem’s never-dry, Prohibition-defying nightclubs together catered to and encouraged an “anything goes” atmosphere, drawing all sorts of eccentric subcultures to the heart of the action.

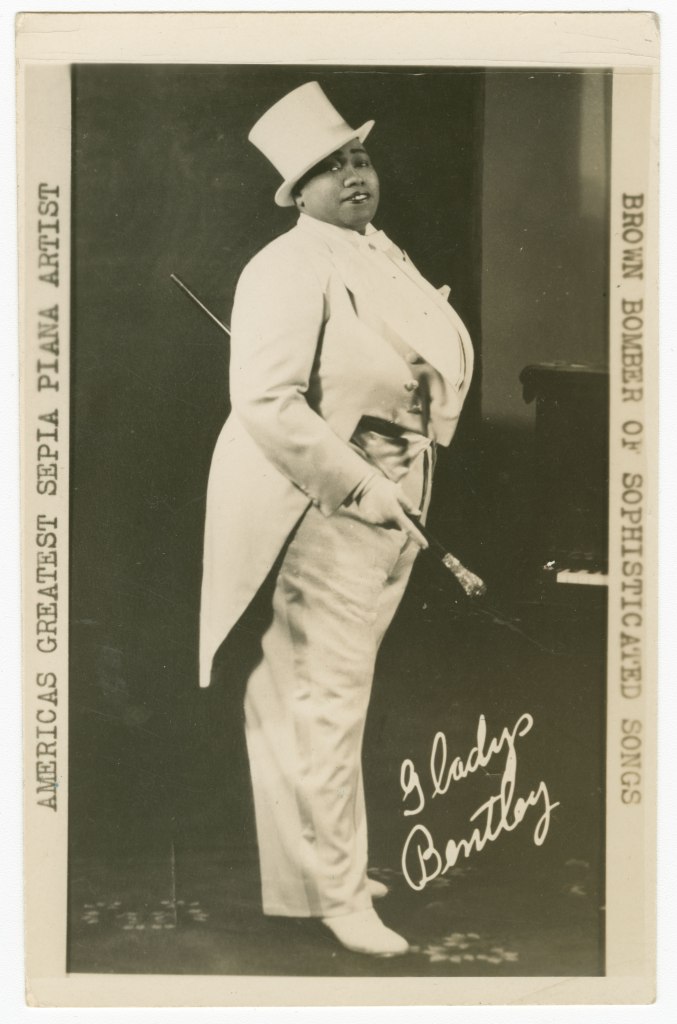

Here, Bobbie was free to be, and what she became was a Harlem legend in a white top hat and full tux, who stomped her feet with the same ferocity that she banged on her piano, transforming innocuous radio-friendly songs into lusty howlers, and unapologetically flirting with every woman in her audiences. In her own original songs, themes of female independence from gender norms and escaping abusive relationships dominated her lyrics, and her signature trumpet-scatting filled the space between. Crowds packed into the variety of clubs Bobbie headlined, hoping in particular to hear her barn-burner “Nothing Now Perplexes Like the Sexes, Because When You See Them Switch, You Can’t Tell Which is Which.”

But for Bobbie, that night at King’s Terrace and the padlock police used to shut the club down only symbolized the beginning of her end in New York. Financial woes plaguing the populace during the Great Depression in the 30s and the end of Prohibition brought the nightclub scene to a grinding halt. The woman who’d once boasted record deals, a $5,000 a month apartment on Park Avenue, and sold out every show would have to find a new home for herself and her act.

Luckily, her fame already preceded her nationwide with tours that took her to Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and as far as California, where she ultimately decided to move. As Los Angeles’ “Brown Bomber of Sophisticated Songs” and “America’s Greatest Sepia Piano Player” she once again dazzled audiences, but it was clear her Harlem heydays were long gone. Laws passed in California forced her to carry special permits to wear men’s clothes and increasing public distaste for non-gender-conforming people continued to stifle the flamboyant show that put Gladys on the map.

By the 1950s, black celebrities who dared to oppose social conventions were being dragged into and condemned at all-white government hearings, victims to McCarthyism and the Red Scare. Her already declining career couldn’t suffer another blow, and in 1952, Gladys submitted an editorial feature to EBONY Magazine, declaring herself cured of her “third sexuality.”

But in that same article, Gladys slipped a telling insight. “Some of us wear the symbols and badges of our non-conformity,’ she observed. “Others, seeking to avoid the censure of society, hide behind respectable fronts, haunted always by the fear of exposure and ostracism. Society shuns us. The unscrupulous exploit us. Very few people can understand us. In fact, a great number of us do not understand ourselves.“ For someone who claimed to have successfully extracted the “malignant growth festering inside,” her message of self-acceptance and inclusion rang loud and clear.

Sometime over the next 8 years, the bombastic life of Bobbie Minton was put away. Gladys married two different men in short-lived relationships, found religion, and lived with her mother until passing away in 1960 at only 52 years old. Whether Gladys truly found peace with her identity, no one could say, but her brief and once-fearlessly queer life inspired so many to live vibrantly, flout normality, and defy anyone standing in the way of the person they were born to be.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Get all the gossip on the extraordinary Gladys Bentley / Bobbie Minton from BUST Magazine.

Read Gladys’ own words via her EBONY Magazine essay “I am A Woman Again.”