Before boxer Jack Johnson, before sprinter Jesse Owens, and 50 years before first baseman Jackie Robinson all broke color barriers in professional sports, Marshall “Major” Taylor rode for 142 of the most agonizing hours of his life to international cycling stardom.

“The Six Days of New York” cycling event held December 6-12, 1896 at Madison Square Garden drew massive global crowds and 28 cyclists, all there for one of the greatest sporting events of the era. For six straight days, riders would circle the specially-constructed velodrome until the completion of the event, or until only one exhausted competitor remained, whichever came first.

It was 18-year-old Major’s first professional race, and for every ounce of anticipation running through his veins, there was a gallon of fear right behind it. Only 30 years beforehand, slavery had been abolished by the 13th Amendment, so a black man in an elite sport was not only uncommon – he was unwanted. But this black man had earned his place among the talented white cyclists, all many years his senior. He’d blown through amateur bike records on his way to the professional league, and despite the naysayers convinced he was a fluke who could never match up to “real” talent, here he was, the only black competitor among a sea of white racers, journalists and 5,000 spectators on the world stage.

It’d been a rough road to ride though. He’d been threatened, sabotaged, and even banned from tracks in his climb to the top – at one point, resorting to bleaching his skin in an attempt to gain entry as a “white” cyclist. The lightening process was so physically and mentally painful that he vowed he’d never do it again. Besides, their racism pushed him to be stronger, faster, and better than every other rider in the field. He said, “My color is my fortune. Were I white I might not amount to a row of shucks in this business.” Still, as proud as he was to be who he was, Major couldn’t deny his “dread of injury every time I start in a race.”

As he expected, Major spent the next several days being elbowed, boxed in, and even deliberately crashed by the competitors. Each time, he righted his bike, bloodied and bruised, but determined to continue. After day 5 and having ridden for 1,732 miles – the distance between New York and Austin – over 142 hours with no sleep, very little food, and in the throes of hallucination, Major withdrew from the contest, finishing in 8th place.

But it didn’t matter. In those 5 days, Major Taylor had become a legend to the international sporting community, the first black man to ever compete in a six-day race and in impressive fashion. So jarring was the experience, Major never entered another six-day race again, and that didn’t matter either. He won 29 of the next 49 races he DID enter, securing 7 world records along the way – all before he turned 20. It was over 30 years later before the last of his records was finally broken.

Still, Major wanted it all. In 1897, his championship hopes had been dashed when southern promoters and cyclists refused to allow him on their tracks, making it impossible to compete in enough races to qualify for world championships. When their threats, physical attacks, and petty tricks like throwing ice water on him and dropping nails in his path forced Major to avoid the chaos by sprinting to the front of the pack and ultimately still winning, racist cyclists conspired to move races to Sundays in 1898. His devout Christianity was a priority, and once again, despite being in contention for the title, Major fell short of the race requirement.

In 1899, that all changed, and finally, Major dodged every physical, structural, and mental roadblock the all-white establishment threw in his path to become the first African-American world champion in ANY sport, and only the second black athlete in the world to hold a title.

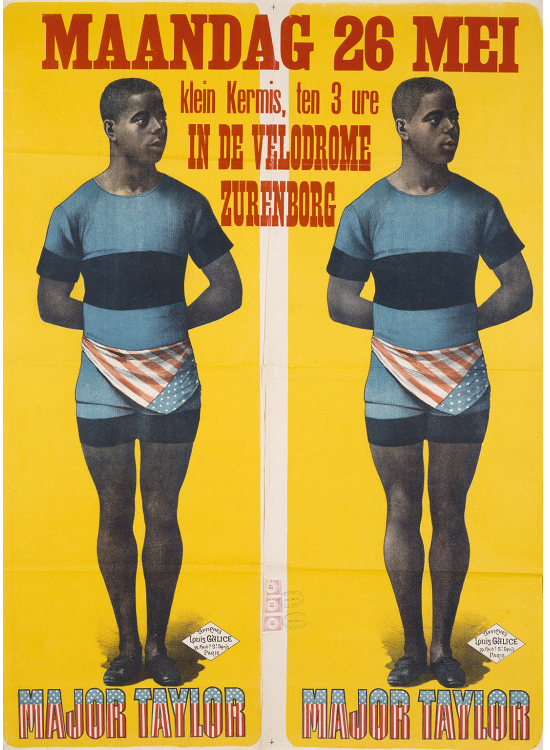

The championships had been held in Montreal, and hearing the “The Star-Spangled Banner” played in celebration of his success, Major later wrote, “I never felt so proud to be an American before, and indeed, I felt even more American at that moment than I ever felt in America.” Despite his global recognition and clear talent, like so many gifted black Americans who came before and after him, Major’s skill amounted to nothing in the face of segregation in the United States. In contrast, he enjoyed superstardom abroad and when he raced in Australia and Europe, including France where he eventually moved, the people and press loved him, nicknaming him “Le Negre Volant,” the flying black man.

At just 32 years old in 1910, Major decided that the round-the-clock schedules, heavy toll on his body, and dangerous racism he still faced from American competitors entered in races abroad had taken enough from him. So with the millions he’d earned from brand endorsements, promotional jobs, and of course, prize winnings from the nearly 20 years he’d competed in amateur and professional cycling, Major retired with all the comforts money could buy. Which was unfortunate, because in the stock market’s decline and eventual historic 1929 crash, Major’s investments were lost as well, and he was penniless. Still, one to overcome every adversity, Major recorded his extraordinary story in his book “The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds: An Autobiography,” which he sold from the trunk of his car.

Only 53 when he died in a Chicago hospital alone and estranged from his family, Major’s death was the polar opposite of his life – unceremonious and unrecognized. By the time his family was notified of his passing, he’d been buried in a pauper’s grave. But even death couldn’t silence his legacy. Learning of Major’s contributions to the sport, iconic bicycle manufacturer Frank Schwinn donated the funds to give him a proper burial in 1948. Major’s newly-placed gravestone was inscribed “World’s champion bicycle racer who came up the hard way without hatred in his heart,” in recognition of a career colored with pioneering achievements and of the equally remarkable content of his character.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Read Sports Illustrated’s take on the full fascinating life of Major Taylor.

Browse digitized historic news coverage of Major’s career and his autobiography at The Library of Congress.