“I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs. I knew at that point I had to have a camera.”

In 1938, Gordon Parks bought that camera, and for just $7.50, he became the first black man to make the world truly see its reflection through his eyes.

And those eyes had seen more in his 26 years than most had seen in a lifetime. Gordon lost his mother as a teenager and had subsequently been homeless, a high school dropout, a piano player and singer, busboy and waiter, semi-pro basketball player, and worked for the Civilian Conservation Corps. But when he chanced upon a discarded magazine featuring photojournalistic images of migrant workers, immediately Gordon envisioned himself as the man behind the camera. “Still suffering the cruelties of my past, I wanted a voice to help me escape it,” Gordon recounted in his autobiography. “I bought that Voightlander Brilliant at a Seattle pawnshop; it wasn’t much of a camera, but.. I had purchased a weapon I hoped to use against a warped past and an uncertain future.”

Whether his camera was a weapon or a good luck charm, right away, things started looking brighter for the young man. From one of his very first rolls of film came his first exhibition, a window display of his images by his developer, the local Eastman Kodak store. On their recommendation, he charmed his way into a job shooting for a women’s clothing store where his good luck just kept on growing. That store happened to cater to Marva Louis, wife of heavyweight champion Joe Louis. In Chicago, there was a true demand for a photographer of his caliber, she teased.

In hindsight, Gordon wrote, “a guy who takes a chance, who walks the line between the known and unknown, who is unafraid of failure, will succeed.” It was easy advice for the man who’d arrived in Chicago and taken freelance jobs shooting on the South Side before winning a fellowship to work in the Washington D.C. Farm Security Administration, the very same agency that’d published the photos inspiring his photography in the first place.

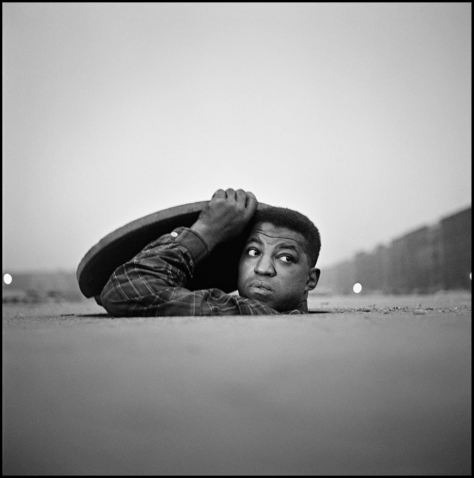

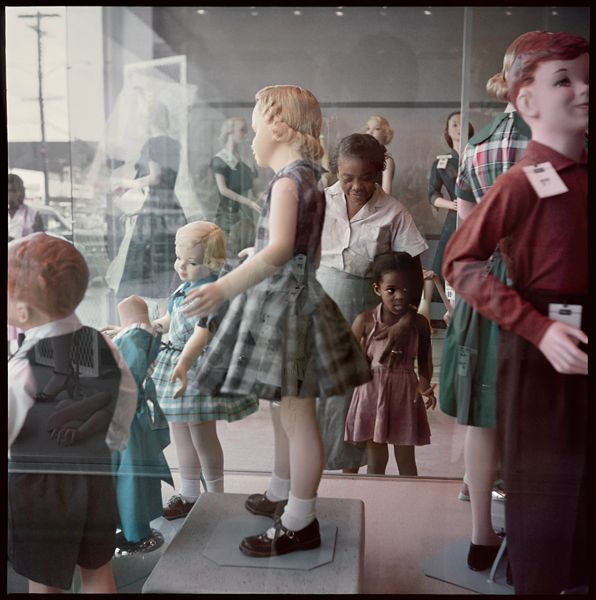

Gordon became an undeniable asset to the FSA in the middle of their campaign to win the hearts and minds of Americans for Roosevelt’s New Deal. Since many voting Americans didn’t know the plights of farmers, migrant workers and rural towns the New Deal was expected to help most, the FSA had been tasked with photographing that demographic sympathetically. Gordon was crucial in that effort. The extremely poverty-stricken (of all races) and people of color could allow themselves to be vulnerable to a black man who was himself already accustomed to being invisible. His photographs, including one of his most famous taken right in the offices of the FSA, were full of raw emotion and evocative scenery unlike any other captured during the mid-30s and 40s.

By then, his humanizing eye had gained a following of its own beyond the public sector, and when Gordon finally hung up his government service hat in 1943, he relocated to Harlem, where a very famous name was waiting for his services next: Vogue Magazine. At a time when some black American men were still being lynched for looking at white women, one of the world’s most recognized fashion publications sought out Gordon’s gaze as their first black photographer.

With fashion came with its own vast new world of photographic techniques, settings and points of view. Gordon dominated them all. But for a photographer used to shooting portraits and candids, fashion photography came with its own challenges. Namely, models. Their over-posing and intense awareness of the camera didn’t fit his vision of how real women wanted to see fashion, and though he’d spent 5 years delighting Vogue’s readers with his fresh new approach, when LIFE Magazine came calling next, he quickly answered, becoming their first black photographer as well.

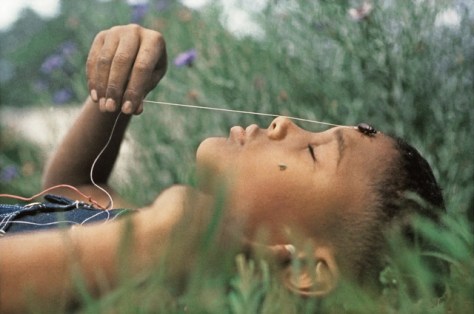

It wasn’t all roses for Gordon though. His willingness to work for white-owned publications made him an outcast in some black communities, and a still racist society meant there were no protections for him, neither in-office nor on assignment. But navigating extremes was nothing new for Gordon, who’d seen some of the best and worst life had to offer before he’d even turned 40. “The pictures that have most persistently confronted my camera have been those of crime, racism and poverty. I was cut through by the jagged edges of all three. Yet I remain aware of imagery that lends itself to serenity and beauty, and here my camera has searched for nature’s evanescent splendors,” Gordon mused.

And for the next 20+ years, LIFE made the most of his vast wellspring of talent, access, and life experience, sending him on assignments that included the Black Panthers and Harlem gangs, celebrities, Parisian life, and even the slums of Rio de Janeiro, where he quite possibly launched the world’s first Kickstarter. When LIFE published his 1961 photo-documentary of a sick little boy named Flavio and the struggle his family faced in Brazil, the magazine’s readers spontaneously donated over $30,000 for the boy’s medical treatment in the States as well as a new home for his family. There were few clearer examples of the weapon he’d formed against poverty and racism doing its work to breaking barriers.

But Gordon had so much more to do. By 1962, he was writing books. By 1968, he was producing his own movies. And finally, by 1971, “Shaft,” his blueprint for the blaxploitation movie, made him the first black man to release a major motion picture, too. “Like souls touching… poetry, music, paint, and the camera keep calling, and I can’t bring myself to say no.”

By the time he died in 2006 at the age of 93, Gordon had won too many photography awards to count, 40 honorary doctorate degrees, the National Medal of Arts, the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal, and hundreds more. But even more significant are the millions of photographs, 12 films written or directed, 12 books and countless other artworks by a man who showed American society how much more of its beauty is visible when seen through a darker lens.

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Browse the archives spanning Gordon’s years and genres of work.

Read Gordon’s compelling life story in his New York Times’ obituary.