There was no room left for the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth on the train leaving Chattanooga one fateful March day.

Unbeknownst to the conductor, along with its standard cargo, his freighter carried a truly volatile situation. When nine assorted black teenagers, a motley crew of white men, plus two white women all happened upon each other while trainhopping on March 25, 1931, their trip aboard the Southern Railroad line sparked one of the most documented, protested, and historically significant miscarriages of justice in United States history.

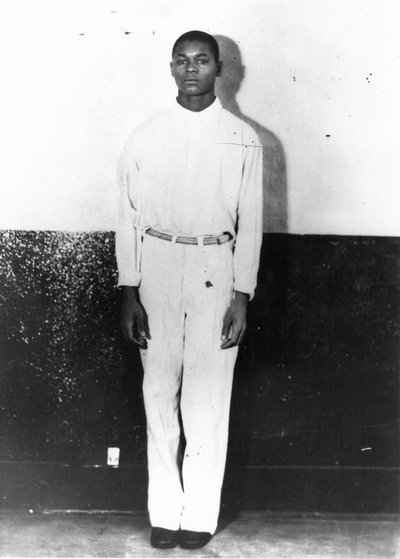

Four of the nine teenagers – Haywood Patterson (18), Eugene Williams (13) and brothers Roy (12) and Andy Wright (19, and the oldest of all) – traveled west together looking for more job opportunities. From seeking medical care to simply heading home, the five additional black men, who were otherwise strangers, had their own reasons to hop the railways. For all nine, the risk of riding trains illegally and their vulnerability to others’ misdeeds or undue punishment should they be caught, was worth the reward waiting at their final stops.

But when someone intentionally stomped young Roy’s hand, the perils of confronting white men didn’t stop his brother and two friends from rushing to his aid, overpowering and throwing Roy’s aggressors from the train. Relieved to have avoided worse, the boys looked forward to finishing their trip with racism behind them. They couldn’t have imagined the lifelong misery that lie ahead.

The story of Roy’s attack had been refabricated into one where he and the three companions defending him were suddenly the villains who started the fight, and according to the two women attempting to avoid trainhopping charges themselves, rapists as well. A mob waiting at the next stop in Paint Rock, Alabama ransacked each car in search of the black men who’d dared to forget their place in the still intensely racist South, snatching all nine.

Fortunately, starting in 1918, anti-lynching bills continually introduced in Congress – though none of the 200 actually passed until 2018 – signaled a growing distaste of lynching by the American public, who beforehand had only taken a stance of disapproving passivity at best. Rather than being handed over to the mob, the nine were imprisoned in Scottsboro, Alabama, and granted one laywer who hadn’t practiced in over a decade, another who practiced real estate law, and a sham of a two-week trial in which eight were immediately convicted and sentenced to death by an all-white jury.

Nearly two years of appeals later, the Alabama Supreme Court STILL upheld all eight convictions. But the scandalous trial had seized the attention of almost every major American news outlet, with even The New York Times urging President Roosevelt to intervene in the glaring discrimination against the Scottsboro Boys. Global protests as far as Cape Town, South Africa and Delhi, India erupted, until finally, the case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court where in 1932, the convictions were overturned on the grounds of insufficient counsel.

But Alabama was relentless, and despite representation from renowned and undefeated New York defense attorney Samuel Leibowitz, when the trials reconvened in 1933, even Samuel’s legal prowess was no match for the all-white jury’s determination to turn eight innocent black teenagers into scapegoats. Doomed to become eight more anonymous black prisoners victimized by a racist justice system, the Scottsboro Boys instead inspired an unexpected moral stand from Judge James Horton who suspended their sentences and any further trials until he could ensure a “just and impartial verdict.” The details from the trial and the tribulations faced by both the Scottsboro Boys and anyone who publicly interfered with their unjust convictions inspired one of America’s greatest pieces of modern literature, Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

And still Alabama persisted. The judge was replaced with another who hadn’t attended a single day of law school, and after shutting down any attempt at a defense by their northern Jewish lawyer who offended every possible Southern sensibility, two of the eight men were again convicted of a crime they obviously hadn’t committed, while the others awaited retrial. But Samuel wasn’t done fighting for the Scottsboro Boys quite yet. Once again appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1935, he protested Alabama’s use of all-white juries, proving that the state forged names to create the appearance of having even considered black jurors. For a second time, the convictions were federally overturned.

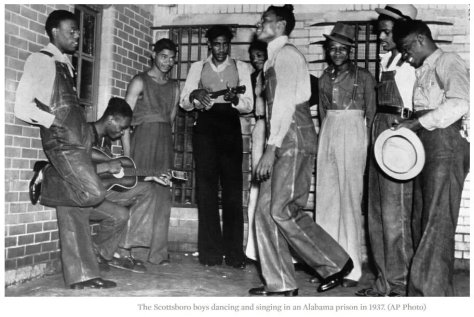

Refusing defeat, the state of Alabama continued their legal lynching, seeing the defendants in and out of prison repeatedly after paroles, parole violations, and new convictions for the next 20 years until their releases, plea bargains or deaths. Finally, in 2013, the Scottsboro Boys were officially exonerated of any crime and pardoned in 2013, over 80 years after their arrest and long after all nine had died.

Despite the “unmitigated tragedy” that Alabama now admits that the Scottsboro Boys suffered at the hands of a racist system clinging to its former glory, those two Supreme Court cases set landmark precedents in jury selection and defendants’ rights. But still, mirrored by modern day cases like the plight of the Central Park Five, that the Scottsboro Boys’ story remains unfinished is a national shame beyond all reasonable doubt.

“This 1936 photograph—featuring eight of the nine Scottsboro Boys with NAACP representatives Juanita Jackson Mitchell, Laura Kellum, and Dr. Ernest W. Taggart—was taken inside the prison where the Scottsboro Boys were being held. Falsely accused of raping two white women aboard a freight train in 1931, the nine African American teenagers were tried in Scottsboro, Alabama, in what became a sensational case attracting national attention. Eight of the defendants were found guilty and sentenced to death; the trial of the ninth ended in a mistrial. These verdicts were widely condemned at the time. Before the young men eventually won their freedom, they would endure many years in prison and face numerous retrials and hearings. The ninth member of the group, Roy Wright, refused to pose for this portrait on account of his frustration with the slow pace of their legal battle.”

(NOTE: Juanita Jackson was the first black woman to practice law in the state of Maryland.)

KEEP GOING BLACK IN HISTORY:

Read individual profiles of the Scottsboro Boys, and find more in-depth coverage of every aspect of their shocking trial here.

The Nation revisits their real-time 1930s coverage of the Scottsboro Boys’ cases in recognition of the men’s 2013 posthumous pardons.

One thought on “DAY 14 — The Scottsboro Boys”

Comments are closed.